Report

Sustainable Agriculture in India 2021

What We Know and How to Scale Up

Niti Gupta, Shanal Pradhan, Abhishek Jain, Nayha Patel

April 2021 | Sustainable Food Systems

Suggested citation: Gupta, Niti, Shanal Pradhan, Abhishek Jain and Nayha Patel. 2021. Sustainable Agriculture in India 2021 – What we know and how to scale up. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

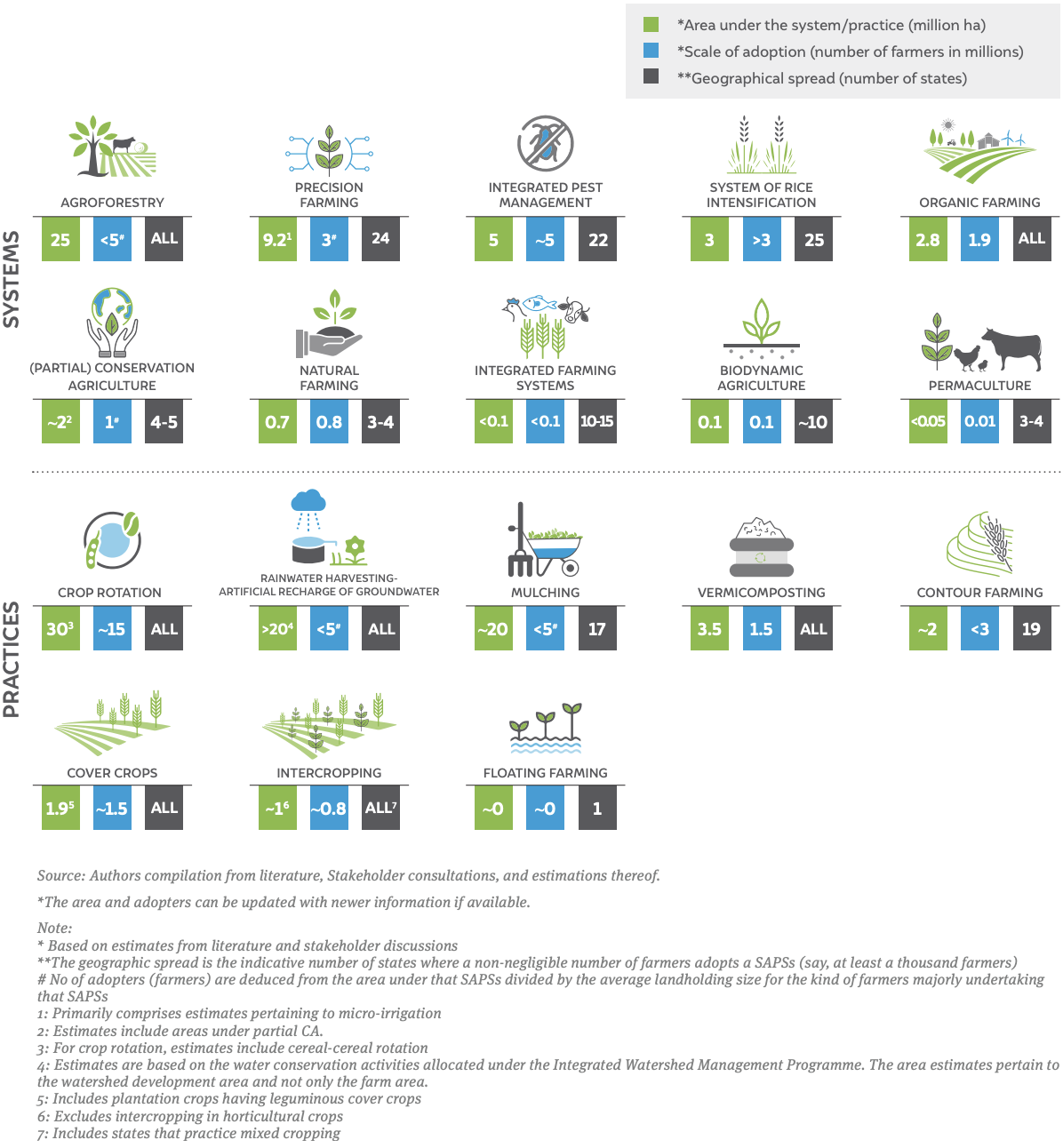

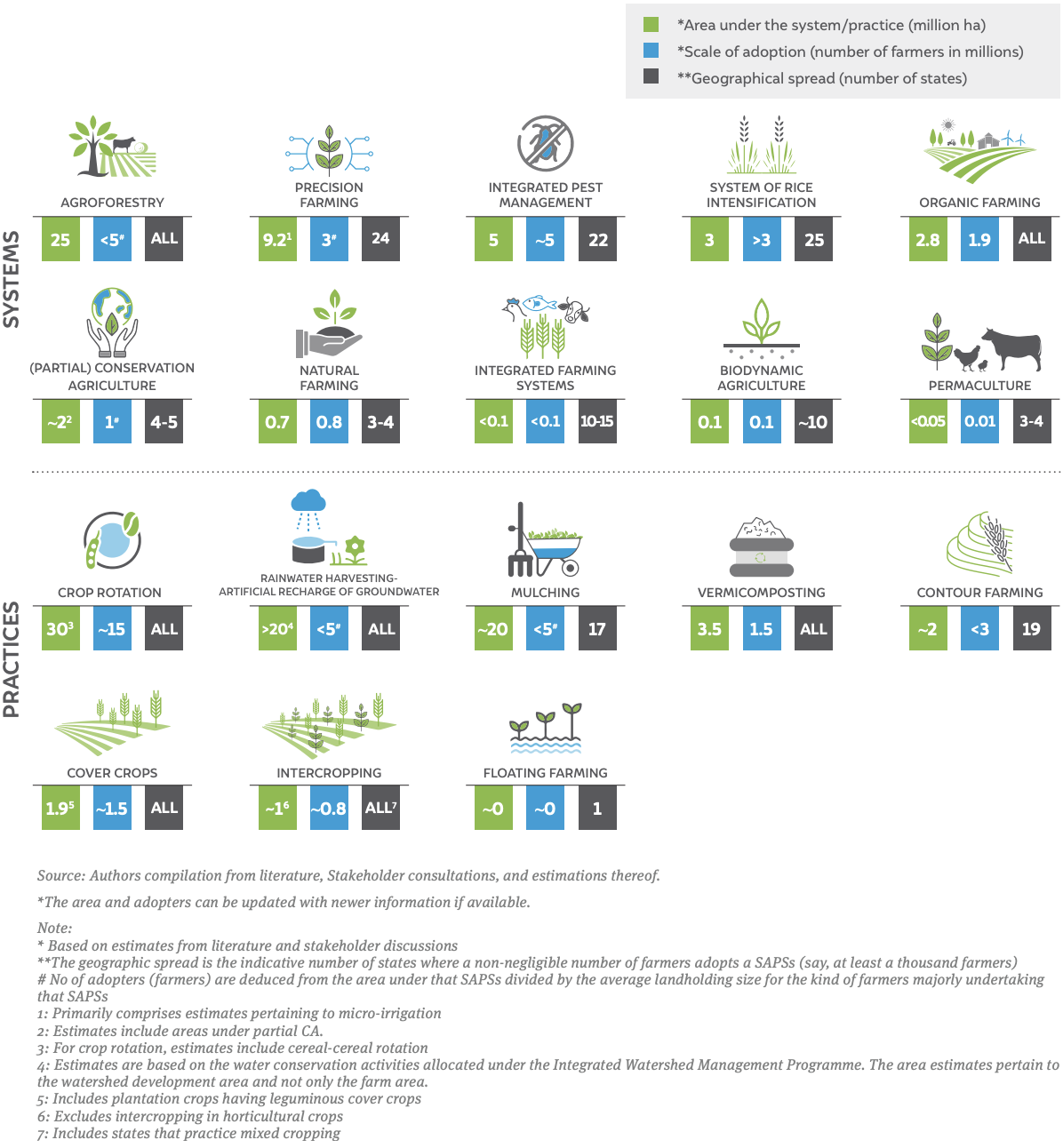

16 Most Promising Practices in Sustainable Agriculture

Click to read more about each practice

Overview

This study, in collaboration with the Food and Land Use Coalition (FOLU), provides an overview of the current state of sustainable agriculture practices and systems (SAPSs) in India. It aims to help policymakers, administrators, philanthropists, and others contribute to an evidence-based scale-up of SAPSs, which represent a vital alternative to conventional, input-intensive agriculture in the context of a climate-constrained future. The study identifies 16 SAPSs – including agroforestry, crop rotation, rainwater harvesting, organic farming and natural farming – using agroecology as an investigative lens. Based on an in-depth review of 16 practices, it concludes that sustainable agriculture is far from mainstream in India. Further, it proposes several measures for promoting SAPSs, including restructured government support and rigorous evidence generation.

Key Highlights

- Sustainable agriculture offers a much-needed alternative to conventional input-intensive agriculture, the long-term impacts of which include degrading topsoil, declining groundwater levels and reduced biodiversity. It is vital to ensure India’s nutrition security in a climate-constrained world.

- While various definitions of sustainable agriculture exist, this study uses agroecology as a lens of investigation. This term broadly refers to less resource-intensive farming solutions, greater diversity in crops and livestock, and farmers’ ability to adapt to local circumstances.

- Sustainable agriculture is far from mainstream in India, with only 5 (crop rotation; agroforestry; rainwater harvesting; mulching and precision) SAPSs scaling beyond 5 per cent of the net sown area.

- Most SAPSs are being adopted by less than five million (or four per cent) of all Indian farmers. Many are practised by less than one per cent.

- Crop rotation is the most popular SAPS in India, covering around 30 million hectares (Mha) of land and approximately 15 million farmers. Agroforestry, mainly popular among large cultivators, and rainwater harvesting have relatively high coverage - 25 Mha and 20-27 Mha, respectively.

- Organic farming currently covers only 2.8 Mha — or two per cent of India’s net sown area of 140 Mha. Natural farming is the fastest growing sustainable agricultural practice in India and has been adopted by around 800,000 farmers. Integrated Pest Management (IPM) has achieved a coverage area of 5 Mha after decades of sustained promotion.

Sustainable agriculture practices and systems in India (2021) – key statistics

- Agroforestry and system of rice intensification (SRI) are the most popular among researchers studying the impact of SAPSs on economic, environmental, and social outcomes. Evidence for the impact of practices such as biodynamic agriculture, permaculture and floating farming are either very limited or non-existent.

- The existing literature critically lacks long-term assessments of SAPSs across all three sustainability dimensions (economic, environmental and social). Other research limitations include a research gap concerning landscape, regional or agroecological-zone level assessments and a relative lack of focus on evaluation criteria such as biodiversity, health and gender.

- The budget outlay for the National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture (NMSA) is only 0.8 per cent of the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare’s total budget - INR 142,000 crore (excluding INR 71,309 crore spent annually on fertiliser subsidies by the Centre).

- Eight of the 16 practices identified by the study receive some budgetary support under various central government schemes. Of these, organic farming has received the most policy attention as Indian states, too, have formulated exclusive organic farming policies.

- Most Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) involved in SAPSs were active in Maharashtra, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh. Organic farming, natural farming and vermicomposting get the most interest from CSOs.

Key Emerging Themes in India’s Sustainable Agriculture

- The role of knowledge: Most SAPSs are knowledge-intensive and successful adoption require knowledge exchange and capacity building among farmers.

- The reliance on farm labour: Since SAPSs are niche, the mechanisation for various input preparations, weed removal, or even harvesting in a mixed cropping field is not mainstream yet. Hence, SAPs are labour-intensive, which may hinder their adoption by medium to large farmers.

- Motivation: The negative long-term impacts of conventional agriculture are pushing farmers to search for alternatives. Further, farmers in resource-constrained environments who do not use significant external inputs are also willing to make the incremental shift to SAPSs.

- Role in food and nutrition security: SAPSs improve farmers’ food security by diversifying their food and income sources. They also enhance nutrition security for families subsisting on agriculture. However, both these aspects call for further research.

Key Recommendations

- The scale-up could start with rainfed areas, as they are already practising low-resource agriculture, have low productivities, and primarily stand to gain from the transition.

- Restructure government support to farmers by aligning incentives towards resource conservation and by rewarding outcomes such as total farm productivity or enhanced ecosystem services rather than just outputs such as yields.

- Support rigorous evidence generation through long-term comparative assessments of conventional, resource-intensive agriculture on the one hand and sustainable agriculture on the other.

- Take steps to broaden the perspectives of stakeholders across the agriculture ecosystem and make them more open to alternative approaches.

- Extend short-term transition support to individuals liable to be adversely impacted by a large-scale transition to sustainable agriculture.

- Make sustainable agriculture visible by integrating data and information collection on SAPSs in the prevailing national and state-level agriculture data systems.

Sustainable agriculture is far from mainstream in India, with most SAPSs being practised by less than five million (or four per cent) of all farmers. In fact, many are practised by less than one per cent.