A significant reform in the direct benefit transfer (DBT) of power subsidy to electricity consumers is on the anvil through the upcoming National Tariff Policy, and the amendments to the Electricity Act, 2003. The Ministry of Power’s (MOP) press release of June 2020 states that it expects state governments to transfer the subsidy directly to the power distribution companies (discoms) through escrow accounts opened in the name of the beneficiaries (consumers) but operated by discoms. While it has not stated any clear objective behind this proposal, it seems to assuage concerns of discoms that if beneficiaries receive the subsidy directly, they may not pay the discom their dues.

We unpack the implications of the proposed reform to identify both gaps and opportunities for it to achieve the purpose DBTs are expected to deliver.

Clarify the intention of the proposed DBT model

Any DBT scheme potentially fulfils one or more of the following objectives:

In this case, however, the objective of the proposed DBT model of subsidy delivery is not clear, and, without that clarity, other features and parameters cannot be fully developed or their impact measured.

Address gaps in the model for it to deliver

Given the reform is still on the anvil, this is a good time to do a course check on what its impact could be through a case study. The case in point is Andhra Pradesh’s (AP) recent DBT order.

AP’s new DBT for agricultural consumers

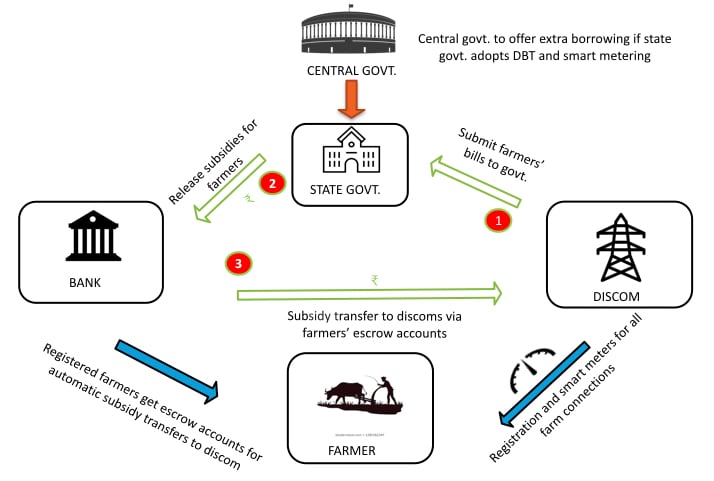

Possibly taking its cue from the MoP’s public declarations, AP has pre-emptively introduced the DBT plan for agricultural consumers, through a recent notification (Order). Farmers in the state will have to register for escrow accounts through which the subsidy transaction will take place from the state government to the discom. The figure below illustrates the proposed flow of subsidies in the AP Order.

The subsidy flow in the AP Order:

Source: Authors' collation based on AP Order notified in Telugu

The state discoms will implement the scheme in one of the districts by the end of 2020, eventually scaling it across the state.

We need to note that by notifying the DBT Order, AP has fulfilled the condition for additional borrowings from the Centre, under the Atmanirbhar Package. At the moment, this eligibility appears to be the primary objective of the state government behind notifying the DBT Order. The Order also proposes the deployment of smart meters for the consumers.

In its current form, we study the implications the Order might have for the beneficiaries and the discoms.

Challenges in implementation

Missing strategy to effectively use smart meters

Smart metering all connections is likely to improve overall accounting and prevent discoms from disguising their losses as subsidised consumption. It would also cut down on meter reading costs. Smart meters can also be very useful in gathering real-time consumption data, and in disconnecting consumers on non-payment. But, the AP Order does not currently reflect any such intent and specifies no plan to set up the infrastructure needed to analyse and use the data smart meters can generate. It is, therefore, unlikely that discoms would reap any benefits from smart-metering while they will have to bear the costs and difficulties involved in deploying such advanced infrastructure.

As the AP Order does not set out any objectives or expected outcomes, it has limited potential to change the status quo. Implementing the Order merely to fulfil the state’s eligibility for additional borrowings would be a waste of public resources.

The idea of a DBT is welcome, but it must have well-defined policy objectives, outcomes and a long-term vision. These objectives can and will differ for each state and each type of consumer. Before the Centre universalises this model, it could consider the implementation in one district of Andhra as a pilot and observe its successes and failures. The lessons from such an exercise could guide the central government and other states to decide on a prudent course of action for subsidy delivery.

Harsha V. Rao is a Research Analyst and Kanika Balani is a Programme Associate at the Council on Energy, Environment and Water. The blog also has research contributions from Sangeeth Raja, Research Intern, CEEW-Centre for Energy Finance. Send your comments to [email protected]

Add new comment