Suggested Citation: Bhasin, Shikha, Bhuvan Ravindran, and Eleonora Moro. 2022. Solar Geoengineering and the Montreal Protocol: A Case for Global Governance. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

Overview

This study analyses the Montreal Protocol as a potential instrument and forum for the global governance of solar radiation management (SRM) research. It creates an analytical framework to examine the objectives, institutional capacity, and jurisdiction of the Montreal Protocol to determine the extent to which it can govern SRM research. The study also puts forth the latest science on the potential impacts of SRM and studies previous attempts at geoengineering governance under different international fora. It recommends certain principles of governance and international law that must underline any proposed framework. Further, it introduces the possibility of an overarching global institution for the complete governance of geoengineering.

Key Highlights

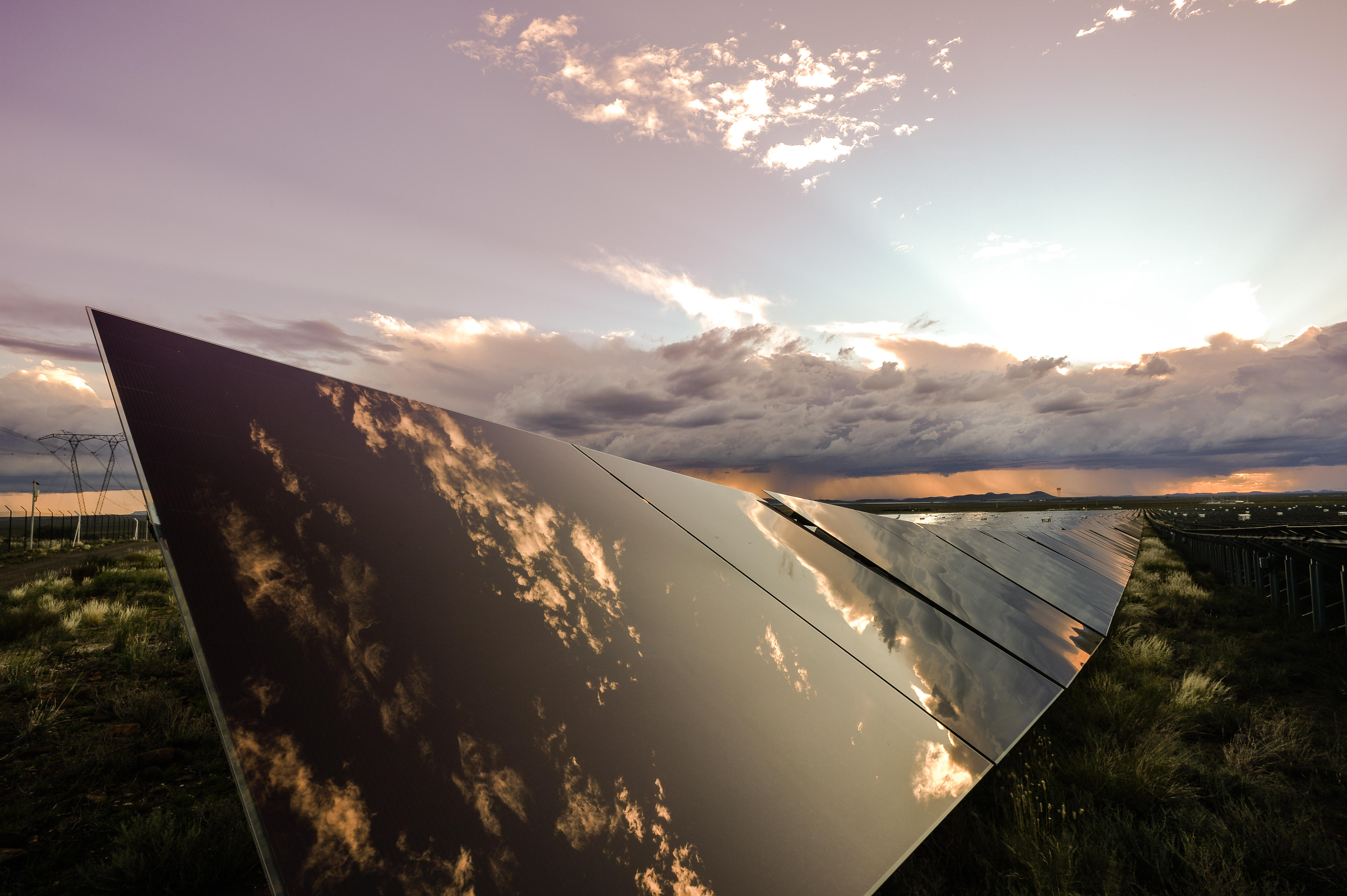

As the climate crisis compounds globally, geoengineering is emerging as a prospective technology cohort to try and slow, or reverse, climate change. Broadly classified into solar radiation management (SRM) and carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technologies, these are drawing increasing attention for their predicted ability to rapidly reduce the impacts of global warming. Unregulated use of SRM technologies could potentially redistribute climatic patterns globally, reduce the availability of sunlight, stunt the growth of plants, increase health risks, and have other unexpected transboundary implications. Stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI), a type of SRM technology which directly injects aerosols to reflect sunlight, has been proven to adversely impact the ozone layer protected under the Montreal Protocol.

This uncertainty, severity, and ubiquity of potential impacts makes SRM research and governance an absolute pre-requisite for conclusively determining its viability. Currently, however, there is an absence of any overarching global environmental agreement to govern these technologies and its research. It is therefore essential to determine a governance framework that prevents SRM from going down the slippery slope of deployment or unregulated spatial experimentation.

This issue brief analyses the link between solar geoengineering research and the Montreal Protocol in an attempt to explore the Protocol’s scope for monitoring such research, either wholly or partially, as suggested by few Parties at the 30th Meeting of Parties (MOP) to the Montreal Protocol in November 2018, namely the Federated States of Micronesia, Mali, Morocco, and Nigeria (Ripley et al. 2018).

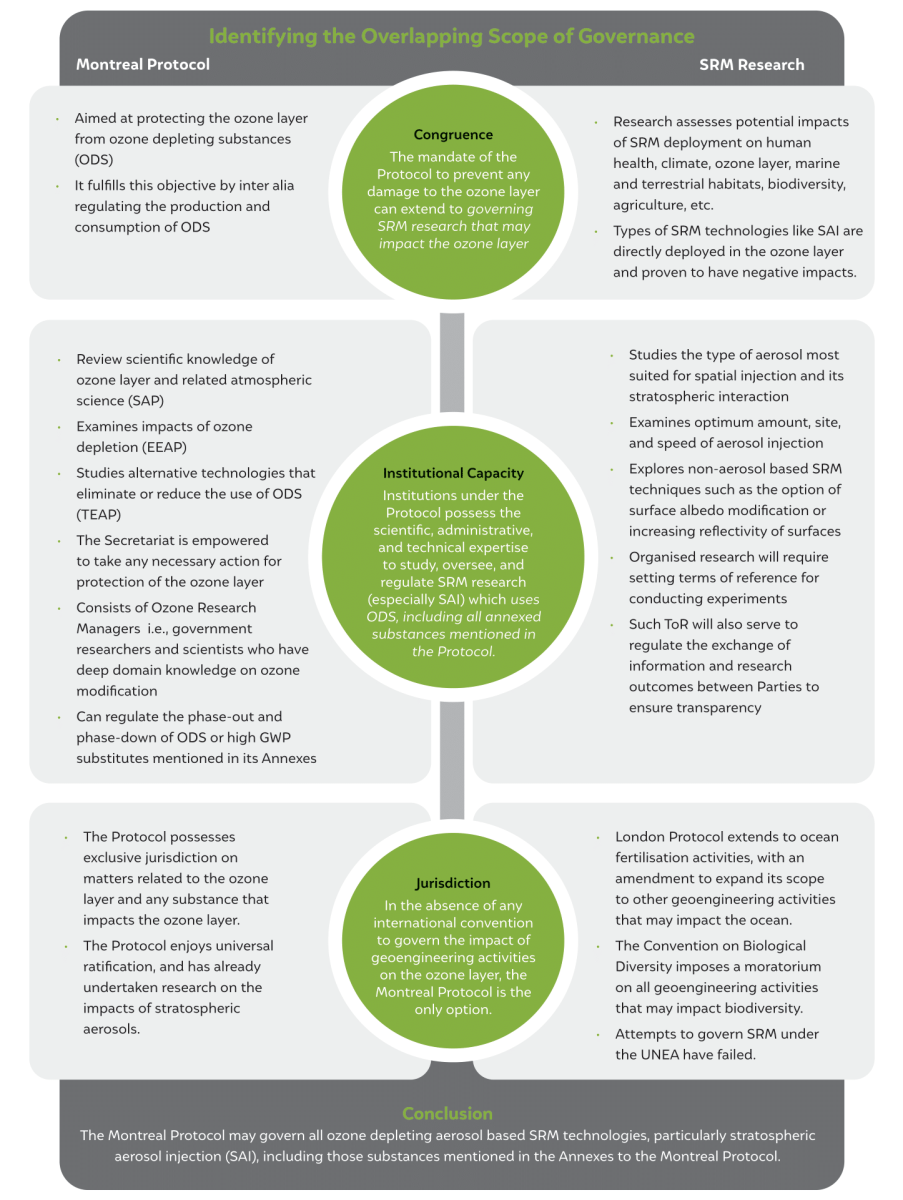

The lessons from various attempts to regulate SRM research under different international fora have been assimilated to explore possibilities of governance of geoengineering research under the Montreal Protocol. These fora include the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA), the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), and the London Protocol. The legal coherence of the Montreal Protocol to govern SRM is examined in this issue brief based on three criteria: (i) congruence, between the mandate of the Protocol and the scope of SRM research, (ii) institutional capacity, and (iii) jurisdiction. The Protocol as a legally coherent instrument is suggested specifically for the governance of SAI technologies, in addition to other SRM technologies that may employ ozone-depleting substances as aerosols, where the term ‘ozone depleting substances’ includes the ‘controlled substances’ listed in the Annexes to the Montreal Protocol.

While advancing this suggestion, and notwithstanding the challenges that it poses, we also nudge the global community to explore possibilities of an independent and overarching framework for SRM governance that transcends the structural constraints of a limited mandate, avoids the overlapping applicability of multiple legal conventions, and overcomes the existing fragmented attempts to regulate research in geoengineering technologies. We highlight the potential global ecological and geopolitical impacts of unregulated SRM experimentation. To overcome possible imbalances, we emphasise on the centrality of transparency as a governance principle for SRM research governance. We further identify key factors that enhance the legitimacy of transparency processes, such as ease of access to information, targeted information, public participation, and reliability. We clearly state that the research, development, and potential deployment of SRM technology must be regulated by the preventive mechanisms of international law as enshrined in the precautionary principle, the principle of transboundary harm, and inter- and intra-generational equity.

We therefore establish the basis for SAI research in particular to be governed under the Protocol, in the absence of a holistic and overarching framework that governs SRM technologies as a cohort in its entirety. We further suggest that the scope of governance under the Protocol could extend to ozone depleting substances, including ‘controlled substances’, employed as aerosols for SRM technologies. This legal congruence, between the scope of SAI research, the nature of ozone depleting aerosols, and the Protocol’s mandate of ozone protection forms the foundation of our proposition.

Source: Author's analysis

Rethinking Ocean Governance in an Era of Climate Urgency

Trust and Transparency in Climate Action

Operationalising the Loss and Damage Fund to Address Climate Impacts

Sustainability-driven Non-tariff Measures