Rural energy demand in India plummeted during the first COVID-19 wave as consumers prioritised spending on essential goods and services other than electricity. Discoms had barely recovered from this heavy jolt when they were hit by the impact of the second wave, which left the rural economy in tatters. The seriousness of the outbreak caused unemployment to rise and made it harder for rural consumers to pay their electricity bills.

Discom's collection counter at a rural sub-division in Gosaiganj, Lucknow district, UP

Image: CEEW

In the past, discoms have tried various ways to boost rural revenues, such as hiring distribution franchises and billing agencies, but with limited success. Our research in UP indicates that rural consumers’ low trust in bills, their inability to comprehend the break-up of bill charges, and their lack of access to easy payment modes are key factors that determine whether or not they pay. In a recent survey of 21 states, we found that 61 per cent of rural consumers visit local discom offices to make payments and that 57 per cent do not find online modes to be suitable alternatives. Also, multiple reports from across states highlight that consumers’ distrust in electricity bills has deepened after the COVID-19 lockdown, resulting in even lower payment rates.

To fix discoms’ billing and collection inefficiencies, the central government is advocating for technological solutions such as smart prepaid meters. But such interventions are unlikely to yield the desired results unless we address the root causes of low rural revenues.

In this blog, we discuss how discoms can improve revenue recovery by learning from women’s self-help groups (WSHGs) in Odisha, who are being lauded for supporting the rural economy and sustaining access to essential services during the pandemic. We also review the gaps that need to be fixed in a similar model recently deployed in Uttar Pradesh.

WSHGs for discom revenue recovery in Odisha

Bijuli Didi, a billing and revenue collection programme, implemented by Odisha’s Feedback Energy Distribution Company’s (FEDCO), demonstrates how a model powered by WSHGs can generate benefits for different stakeholders (see Figure 1). Operationalised in 2013 in Nayagarh district, it engages as many as 133 local WSHGs for billing, revenue collection, and grievance redressal.

Figure 1: Benefits of the Bijulee Didi programme for different stakeholders in Nayagarh district

Source: FEDCO’s presentation on its SHG model and Swami and Wagle (2019)

The model has been replicated in parts of Odisha’s Paradip, Jagatsinghpur and Puri districts. It has also inspired a similar exercise in Uttar Pradesh (UP), albeit one with multiple planning and implementation gaps.

UP’s experiment with WSHG model

In July 2020, the Uttar Pradesh Power Corporation Limited (UPPCL) partnered with the UP State Rural livelihood Mission (UPSRLM) to deploy WSHG agents for door-to-door payment collections. We conducted semi-structured interviews with the following stakeholders to understand how the programme was being implemented:

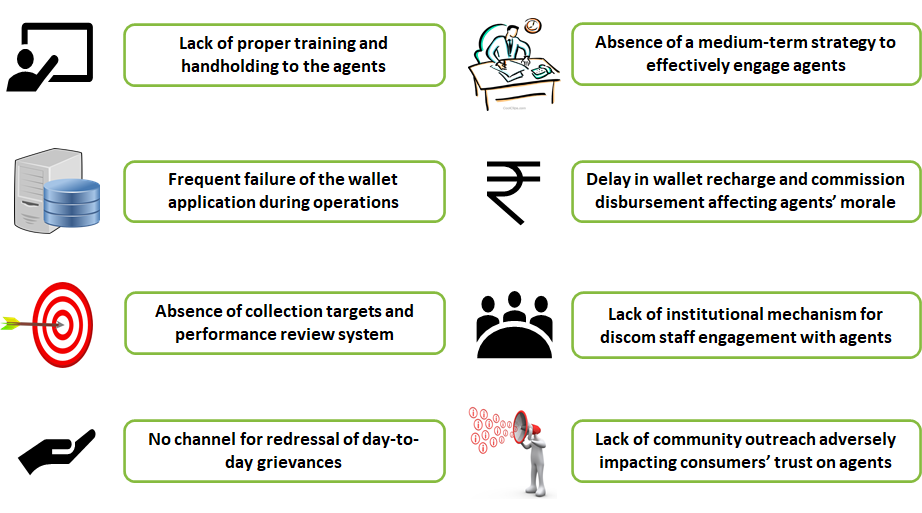

Our research highlights several gaps in the governance of the WSHG model in UP (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Multiple gaps with UP’s SHG model have resulted in poor outcomes

Source: Authors’ analysis based on interviews with stakeholders.

What did the Bijuli Didi model in Odisha get right vis-à-vis the UP model?

In the interactive map below, we highlight the differences in the governance frameworks of both models and the roles of various actors in different processes (Figure 3). We use “Strong Involvement”, “Weak Involvement”, or “Non-Actor” as labels to indicate the extent of the actors’ engagement in each process. We find that the relatively deeper engagement of discom staff in Odisha resulted in better governance outcomes.

Figure 3: Odisha’s WSHG model wins over UP’s owing to its governance structure

Source: Authors’ collation

Odisha’s FEDCO undertook community awareness activities through a dedicated agency-led project management unit (PMU) to increase consumers’ acceptance of WSHGs. In contrast, there is no strategy for community engagement in UP. Notwithstanding these issues, the model has been scaled up in all districts in UP without a proof of concept.

The UP Chief Minister has commended Varsha Pal, a young agent from Lucknow district, for collecting bill payments worth more than INR 5 lakh in her village since August 2020. Pal collaborates with her village’s meter reader and travels door to door to issue bills and collect payments. However, she complains that she did not receive any commission for her work until February 2021. Several other agents, too, complain of similar challenges that might compel them to withdraw from the programme. Further, the sole task of payment collection leaves few incentives for agents to make door-to-door visits, given the poor payment rates in rural UP.

CEEW team with state mission managers for UPSRLM at their corporate office, Lucknow

Image: CEEW

CEEW team with Varsha Pal (WSHG agent) and UPSRLM mission managers in Gosaiganj block, Lucknow district

Image: CEEW

How can discoms improve operational efficiency via WSHGs?

The successful implementation of the WSHG model of payment collection hinges on discoms’ willingness to learn from their peers. Based on lessons drawn from Odisha and UP, we recommend the following measures to help discoms improve their operational efficiency:

WSHGs could act as valuable anchors within the rural community to support discom operations. They could also assist the government with door-to-door dissemination of pandemic-related information and safety equipment. Further, adopting a WSHG-centred model could minimise rural consumers’ interactions with agents from outside their villages and ensure their safety during the COVID-19 crisis.

Add new comment