Suggested Citation: Khanduja, Ekansha, Kartikey Chaturvedi, Aditya Vikram Jain, and Nitin Bassi. 2023. India’s Participatory Groundwater Management Programme: Learnings from the Atal Bhujal Yojana Implementation in Rajasthan. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

This study, in collaboration with the Ministry of Jal Shakti of the government of India (GoI), assesses Atal Bhujal Yojana, a central sector scheme of India, for the state of Rajasthan, one of the seven Indian states where the scheme is being implemented. Launched in 2019, Atal Bhujal Yojana aims to mainstream community participation and inter-ministerial convergence in groundwater management.

India relies majorly on groundwater for meeting its drinking water and agricultural production demands, leading to its emergence as the largest abstractor of groundwater in the world. However, sustainability is threatened. The invisible and dynamic nature of groundwater, coupled with the anthropological and natural threats, made the need for community participation in the management of this resource crucial.

Based on desk review and fieldwork in eight out of 16 implementation districts of Rajasthan, the study has captured the perspective of implementers at state, district, and panchayat levels within the groundwater department, line departments, and civil society space and beneficiaries. It aims to gather insights into the knowledge of the various respondents on the scheme and its various components, and the enabling and hindering factors in implementing/ accessing the scheme. These insights are then assimilated to provide a strength, weakness, opportunity, and threat analysis of the scheme; and recommendations to strengthen the implementation.

Groundwater constitutes about 99 per cent of readily accessible freshwater (United Nation 2022). This invaluable resource plays a crucial role in satisfying the water demands of billions of stakeholders worldwide, spanning rural and urban areas and the industrial and irrigation sectors. As the more easily accessible surface water resources are being over-appropriated and their availability adversely impacted by climate change, reliance on groundwater has increased significantly.

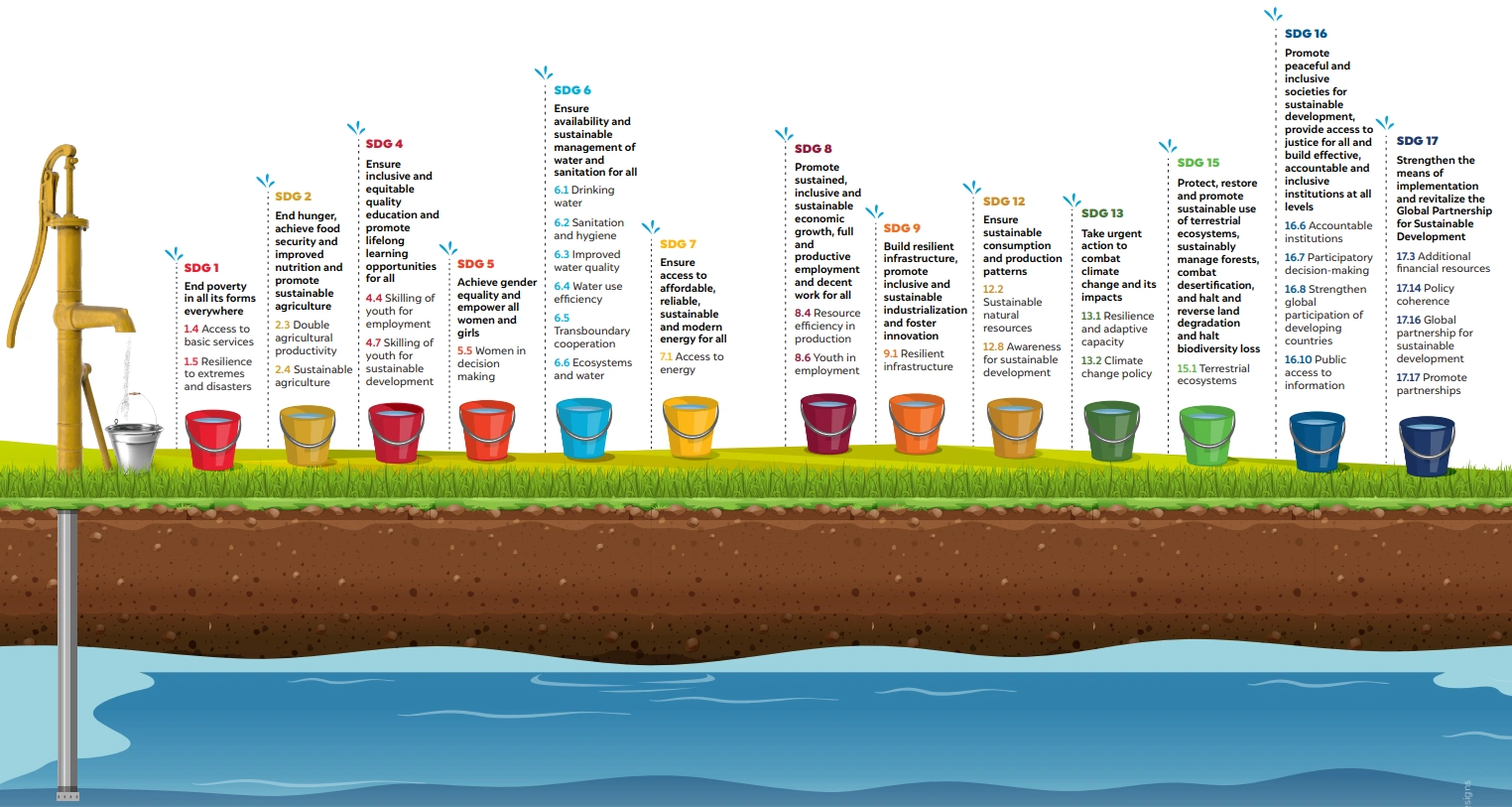

In India, groundwater has played a major role in sustaining the nation’s economy, preserving its environment, and improving standards of living. However, the past few decades have seen an increase in groundwater extraction, with some regions extracting more than the annual replenishment rate. Moreover, this accelerated rise in groundwater extraction has largely been unplanned and unmanaged. Although in the past some efforts were taken to promote the sustainable management of groundwater resources, in the absence of proper statutory backing to regulate groundwater use in agriculture at the national and state level, its governance remains a challenge. In this context, in 2019–20, the Government of India (GoI) launched the Atal Bhujal Yojana (ABY), a central sector scheme, to arrest the decline in groundwater levels and improve the governance of groundwater resources through effective community participation, especially in units (usually blocks) that are over-exploited (stage of groundwater development more than 100 per cent). The scheme has an outlay of INR 6,000 crore (USD 840 million ) (DoWR,RD&GR 2023a) of which 50 per cent is a loan from the World Bank and the rest is from the GoI, given as grant-in-aid to the implementing states. From 2020–21, the scheme is being implemented in selected water-stressed areas in seven states: Gujarat, Haryana, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh, for a period till 2024-25. The scheme has potential to achieve the targets under many Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) including 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 12, 13, 15, 16 and 17 (refer Figure ES1).

In this report, we present an assessment of the scheme through desk review and field visits. We examine its implementation status, key drivers of success (strengths), implementation challenges (weaknesses), opportunities for improvement, and outside threats affecting the scheme’s sustainability. Further, we provide actionable recommendations to improve governance and implementation in the next phase based on the rapid but extensive field research conducted in selected districts of Rajasthan. We also present learnings for other countries to enable community-based participatory groundwater management. This study was undertaken at the behest of the National Program Management Unit (NPMU) of the ABY, under the aegis of the Ministry of Jal Shakti (MoJS), GoI.

Figure ES1 Potential SDG goals and targets that can be achieved through the Atal Bhujal Yojana

Source: Authors’ analysis

We conducted this study using an eclectic methodological approach and deployed qualitative and quantitative tools. It consisted of two phases (Figure 3). Phase I consisted of an exposure visit to Jaipur (where the State Program Management Unit (SPMU) office is located) and the neighbouring district (Dausa) to understand the conditions on ground. The learnings from Phase I were used to develop separate set of questionnaires to gauge stakeholders’ responses on implementation of the scheme. These questionnaires were administered in districts selected for phase II, i.e., Ajmer, Hanumangarh, Karauli, Jaisalmer, Kota, and Chittorgarh.

The fieldwork for both phases was conducted by a team of three researchers during the months of August and September 2023. In phase II, 17 members from District Program Management Units (DPMUs), 24 members from the District Implementing Partners (DIPs), and 25 GP members were interviewed. Focussed-group discussions (FGDs) were conducted with 17 village water and sanitation committees (VWSCs) in six districts. In addition, 29 respondents from seven line departments in the selected districts were interviewed. The data cleaning and analysis were undertaken using Microsoft Excel. The responses from each stakeholder were analysed and categorised to match the respective disbursement-linked indicators (DLIs). The analysis was synergised with the Quality Council of India (QCI) methodology for DLI verification. The results and findings have been reported only for districts covered in phase II.

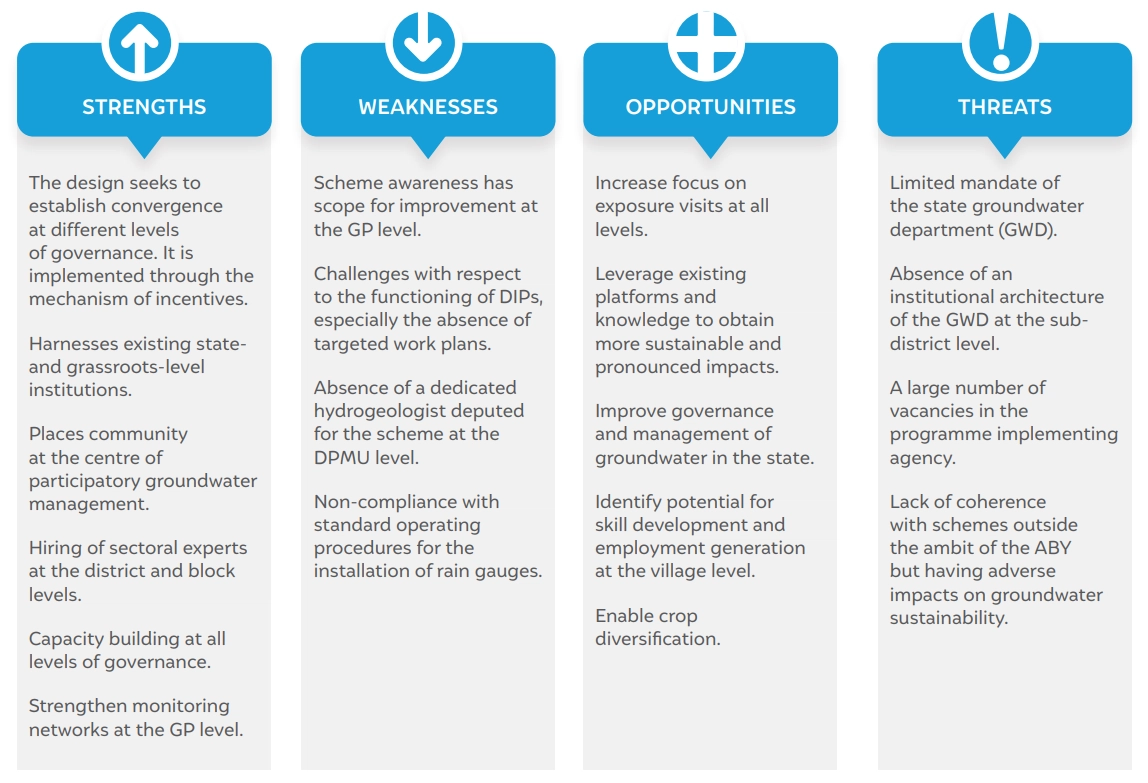

A strength, weakness, opportunity, and threat (SWOT) analysis was carried out to help address the challenges identified, so that a bigger impact can be made in the future. This is presented in Figure ES2.

Figure ES2 A SWOT analysis of the Atal Bhujal Yojana implementation in Rajasthan

Source: Authors’ analysis

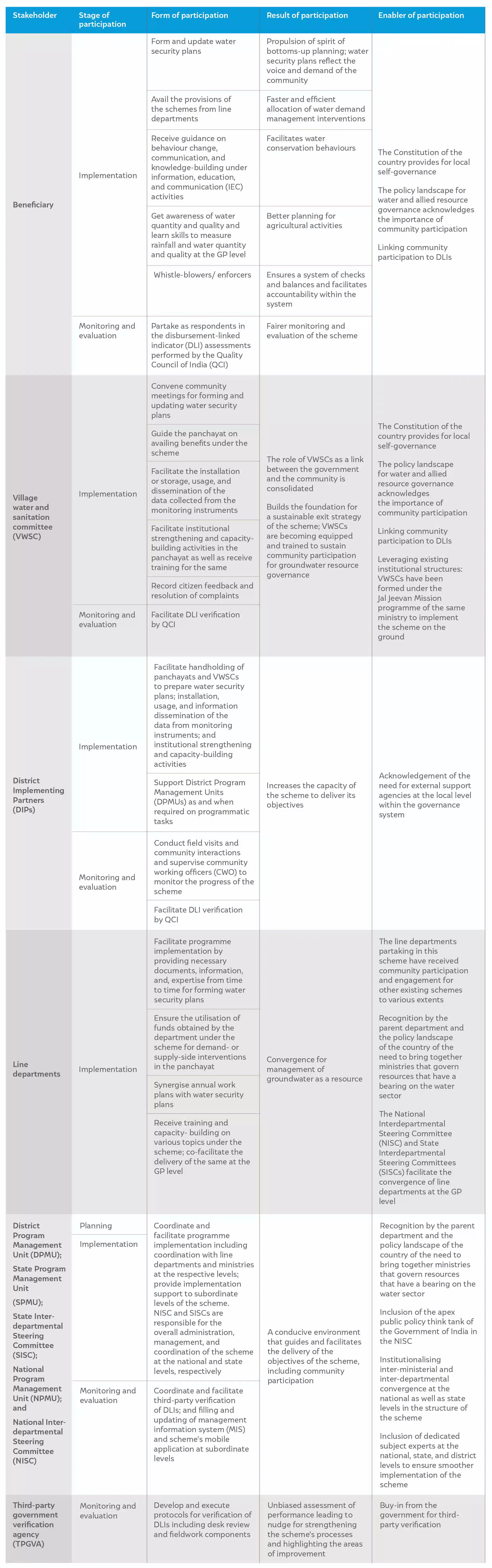

Atal Bhujal Yojana (ABY) offers essential lessons for other countries to enable communitybased, participatory groundwater management and achieve sustainable development goals (SDGs). They are presented in Table ES1.

Table ES1 Stage, form, results, and enablers of participation at the gram panchayat (GP) level

Source: Authors’ analysis

Atal Bhujal Yojana is a central scheme launched by the GoI in 2019, with the aim to improve sustainable groundwater management through convergence among various ongoing schemes, and with the active involvement of local communities and stakeholders. It is being implemented in selected areas in seven states - Gujarat, Haryana, Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan from 2020-21 to 2024-25, with a total financial outlay of INR 6,000 crore.

The usage of groundwater can be made sustainable by understanding and acknowledging the interlinkages of the resource with other resources and factors in all our decisions on groundwater. This includes the need for resources for drinking water, agriculture, animal husbandry, industry, energy, power, and other ecosystem services; the influence of and on climate change in the present, near future, and distant future; and its interaction with social, cultural and economic realities of people. By factoring these interlinkages, we can use the resource in the present in such a way that it leaves enough for the needs of future generations.

According to the United Nations University's Institute for Water, Environment and Health, water is key to sustainable development. Groundwater, which is about 99% of the available freshwater resource on Earth, can support attaining 53 SDG targets under 13 SDG goals.

There are many ways of engaging the community in the management of groundwater, depending on the interest of the community and the legal and policy provisions prevailing in the geography. For example, the community could be engaged in deciding groundwater allocation at the local level, monitoring its quality and quantity, making and implementing management plans and demand reduction measures, negotiating with other actors in regard to the use and governance of the resource, protecting the resource, and negotiating or settling disputes regarding resource allocation or usage.

Enabling Circular Economy in Used Water Management in India

Policy Study on Re-calibrating Institutions for Climate Action

Water Balance and Benefit Sharing Approach to Reduce Water Deficit in an Indian River Basin

Toolkit for "Preparing City Action Plans for Reuse of Treated Used Water"

Evaluating Policy Coherence in Food, Land, and Water SystemsEvidence from India