Suggested Citation: Gupta, Niti, Saurabh Tripathi, and Hem Himanshu Dholakia. 2020. Can Zero Budget Natural Farming Save Input Costs and Fertiliser Subsidies? Evidence from Andhra Pradesh. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

This study offers insights into Zero Budget Natural Farming (ZBNF) vis-à-via its effect on the economics of agriculture in Andhra Pradesh. It compares costs of ZBNF inputs and practices with the costs of chemical inputs (fertilisers and pesticides) for the farmer and also estimates the potential savings in fertiliser subsidies at different stages of ZBNF penetration for the state. The study was conducted through a primary survey of about 600 farmers across all agro-climactic zones in Andhra Pradesh.

Since the Green Revolution of the 1960s, agriculture in India has relied heavily on chemical fertilisers and pesticides. Over the years, their excessive use has resulted in their diminishing marginal utility leading to declining net incomes and growing debt for farmers. Their excessive application also poses a threat to soil health, groundwater purity, local biodiversity, and human health. The inherent unsustainability of chemical-based agriculture and its contribution to the ecological and agrarian crises had resulted in a growing demand for alternative agroecological farming practices that promise a host of ecological and social benefits.

Zero budget natural farming (ZBNF) – a sustainable agricultural system – is one such alternative to chemical fertiliser based agriculture and high input cost agriculture. It exemplifies agroecological principles where the emphasis is on “enhanced soil conditions by managing organic matter and soil biological activity; diversification of genetic resources; enhanced biomass recycling; and enhanced biological interactions” (Khadse, et al. 2018). The practice advocates 100 per cent elimination of synthetic chemical inputs (fertiliser and pesticides) and encourages the application of natural mixtures made using cow dung, cow urine, jaggery, pulse flour etc., mulching practices, and symbiotic intercropping. The practice could potentially reinvigorate rural economies and reduce credit risks for farmers caused by high-input resource-intensive chemical farming. It will also help agricultural families retain greater resources to spend on their well-being for needs such as education, health, and financial security (Tripathi, et al. 2018). At the same time, the practice holds promise for improving biological soil health and local biodiversity, enhancing the climate resilience for crops, contributing towards the Sustainable Development Goals, and supporting the achievement of the Global Nutrition Targets 2025 of access to affordable and safe food.

In 2015, the Government of Andhra Pradesh mandated Rythu Sadhikara Samstha (RySS), a state-owned, non-profit organisation to scale-up ZBNF practices to cover all six million farmers and eight million hectares of agricultural land in the state by 2024. In the face of agrarian distress, the programme aims to promote climate-resilient, chemical-free, ecological agriculture and provide small and marginal farmers with profitable livelihoods from agriculture. The programme was launched in 2015–16 and its implementation in the field started in 2016–17. As of July 2019, more than 500,000 farmers have enrolled in the programme across all 13 districts in Andhra Pradesh, covering an area of around 204,000 acres. The implementation of this project at scale could help India make significant progress towards almost a quarter of 169 SDG targets as outlined by Tripathi et al. (2018).

The Government of India allocates a sizeable portion of its budget to agricultural subsidies – with fertiliser subsidies being the most dominant, amounting to close to INR 70,000 crore (USD 9,758 million) in 2018–19. The projection for 2019–20 is a 14 per cent increase to INR 79,960 crore (USD 11,110 million). The urea subsidy alone corners more than 60 per cent of the allocation, amounting to INR 53,629 crores (USD 7,472 million), and the rest is nutrient-based subsidies (Economic Times 2019). We estimate the total outlay on fertiliser subsidies in 2017–18 in Andhra Pradesh alone to be INR 3,485 crore (close to USD 490 million). During this time, the consumption of urea in Andhra Pradesh was reported to be 14,00,000 tonnes and that of diammonium phosphate (DAP) was a little over 326,000 tonnes. In addition, the sales of a range of complexes was reported to be close to a million tonnes (Fertiliser Association of India [FAI] 2018).

If ZBNF was scaled up across Andhra Pradesh, it would considerably alter the landscape of chemical inputs in agriculture, particularly fertilisers. The avoided fertiliser subsidies from scaling ZBNF would lead to significant budgetary savings, which could be redirected towards more sustainable uses, including funding ZBNF scaling up efforts. This CEEW study was carried out to improve the current understanding of ZBNF and aims to highlight the differences between ZBNF cohorts and those practising chemicals-based agriculture in terms of fertiliser consumption. It also provides an estimate for the savings in fertiliser subsidies resulting from reduced fertiliser consumption due to ZBNF adoption.

We surveyed 639 farmers across six agro-climatic zones of Andhra Pradesh to estimate reductions in self-reported fertiliser use attributable to ZBNF adoption. We adopted a stratified random sampling approach to select the districts, mandals (sub-districts), villages, and farmers. The districts sampled were Srikakulam, Vizianagaram, West Godavari, Krishna, Kadapa, and Anantapuram. The survey instrument captured information on the socioeconomic characteristics of the farmers and data on their landholding size, crops cultivated, input costs, and chemical and natural fertiliser consumption. We also conducted focus group discussions (FGDs) with farmers and semi-structured interviews with retailers and officials from the state Fertiliser Wing to qualify our findings.

Prior to data analysis, the data was tested for outliers and erroneous values using information from the Directorate of Economics and Statistics (2018) and Agriculture Census (2015–16) and 58 observations were dropped from the sample. Thus, the working sample for this study is 581 farmers across six districts of which 254 farmers (44 per cent) are practising ZBNF and 327 (56 per cent) are practising conventional farming using chemical fertilisers.

From our discussions with farmers, we learnt that the transition from chemical-based practices to natural farming is an incremental and iterative process. Farmers could start natural farming by adopting a few of the practices and principles initially and testing them in a small portion of their land. A vertical transition phase will include shifting from a few natural practices to using all-natural inputs and complete elimination of synthetic fertilisers and pesticides. Until then, they are referred to as chemical partial farmers. A horizontal transition happens when the complete landholding of a farmer is brought under natural farming.

In our sample, out of the 254 ZBNF farmers, 77 per cent use all-natural inputs and the remaining 23 per cent are partial ZBNF farmers, which means that they use a few critical natural farming practices, but are also using some amount of chemical inputs on their ZBNF land. For convenience, we refer to them as complete and partial ZBNF farmers in this study. We also observed that 36 per cent of ZBNF farmers are practising it in 100 per cent of their landholdings and using only all-natural inputs, while the remaining 64 per cent are currently practising it in some portion of their total landholding. In this study, we have collected information on various inputs from ZBNF farmers only for the cultivated land in which the farmers were practising ZBNF, as opposed to the farmer’s total land. In our analysis, we include all 254 farmers as part of the ZBNF cohort, including the partial ZBNF farmers as well.

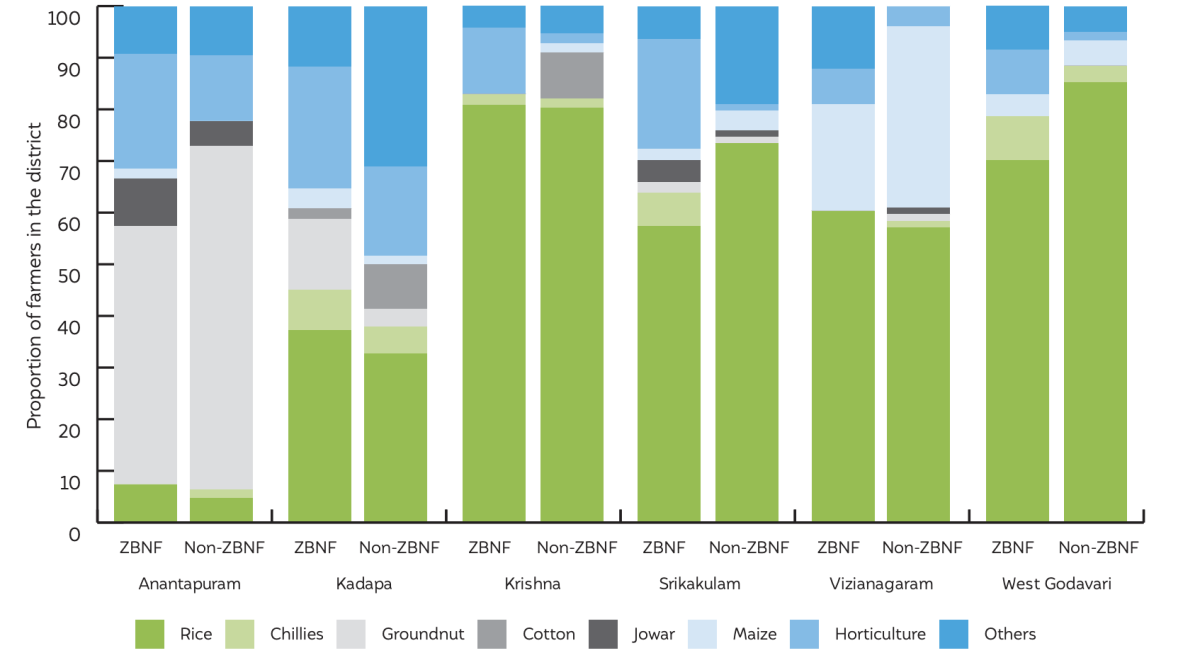

The sample in this study is broadly representative of the major crops grown in Andhra Pradesh – a parameter that we expect drives fertiliser consumption. In our sample, 63 per cent of farmers cultivated rice as the principle crop in the kharif season, 13 per cent cultivated groundnut, and 6 per cent maize. We limit the crop-level analyses in this study to rice, groundnut, and maize, for which we have a sufficient number of observations to derive inferences.

ES1: ZBNF farmers were growing more fruits and vegetables as their kharif crop compared to nonZBNF farmers

Source: Authors’ analysis

We also found that almost twelve per cent of ZBNF farmers were growing fruits and vegetables as their main kharif crop as compared to three per cent of non-ZBNF farmers. Such a shift in cropping pattern could be the result of multi-cropping and inter-cropping – both of which are strongly encouraged under ZBNF – and could critically alter the relative production of various food crops in the state. The change could likely contribute towards a balanced diet for agricultural households and consumers at large, with a potentially higher and more resilient income for agricultural households.

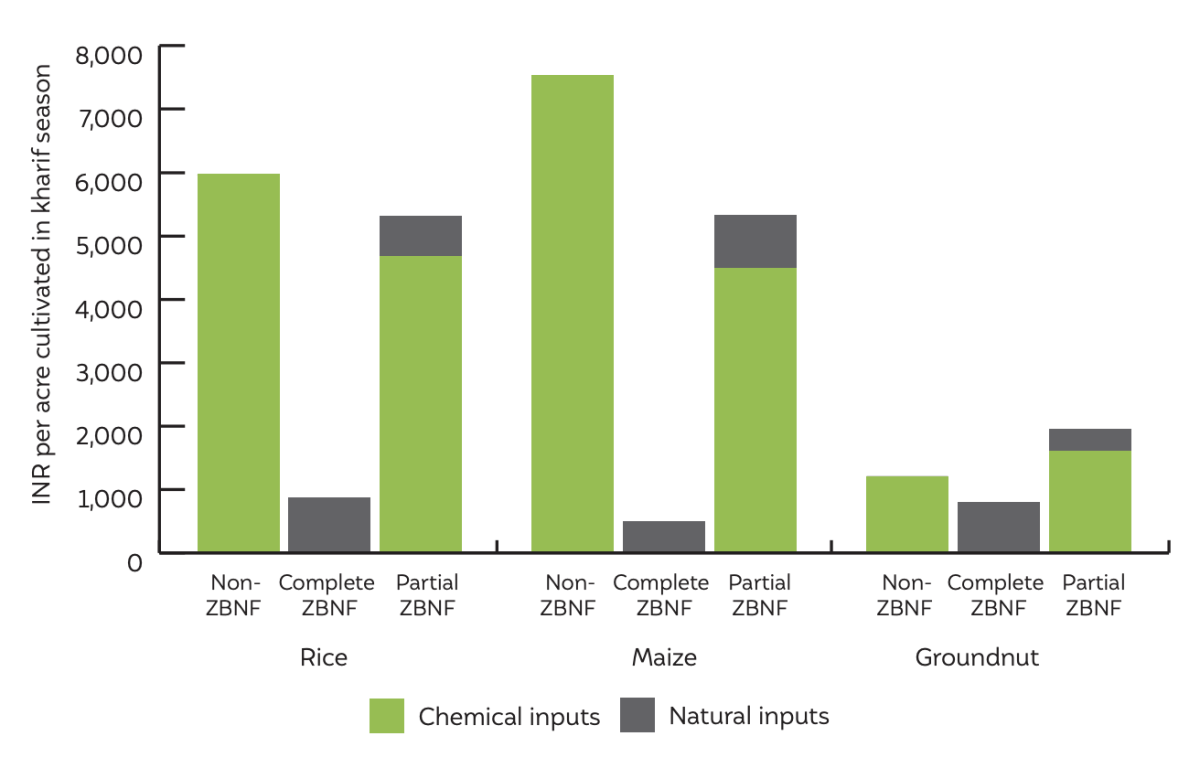

The cost of chemical fertiliser and pesticide are zero in case of a complete ZBNF farmer and it is lower in a partial ZBNF farmer vis-à-vis a chemical farmer. We found a difference of almost 90 per cent in the expenditure on fertilisers and pesticides between the two cohorts for rice cultivators. On an average, chemical farmers cultivating rice spent INR 5,961 (SD: INR 4,496) on chemical inputs while a complete ZBNF farmer incurred an expenditure of INR 846 per acre (SD: INR 785) on natural inputs. Partial ZBNF farmers, who used some amount of both, natural and chemical fertilisers, reported an average expenditure of INR 4,664 per acre (SD: INR 3,176) on chemical inputs and INR 652 (SD: INR 823) on natural inputs, which is still marginally lower than using all chemical inputs.

We found a significant difference of 93 per cent in fertiliser expenses between the two cohorts for maize as well. Complete ZBNF farmers spent INR 503 (SD: INR 414) on natural inputs, whereas chemical farmers, on an average, spent INR 7,509 per acre (SD: INR 4,382) on chemical fertilisers inputs. For groundnut, a chemical farmer spent INR 1,187 per acre as against INR 780 per acre by a complete ZBNF farmer. A partial ZBNF farmer, however, reported an even higher amount of INR 1,936 per acre, on both natural and chemical inputs.

ES2: Average input cost on fertilisers and pesticides drops significantly for ZBNF rice and maize farmers

Source: Authors’ analysis

It is important to note that several components of chemical inputs such as urea are heavily subsidised by the central government. If we add back the subsidised amount in this calculation, there would be an even higher difference in the fertiliser cost between the two cohorts.

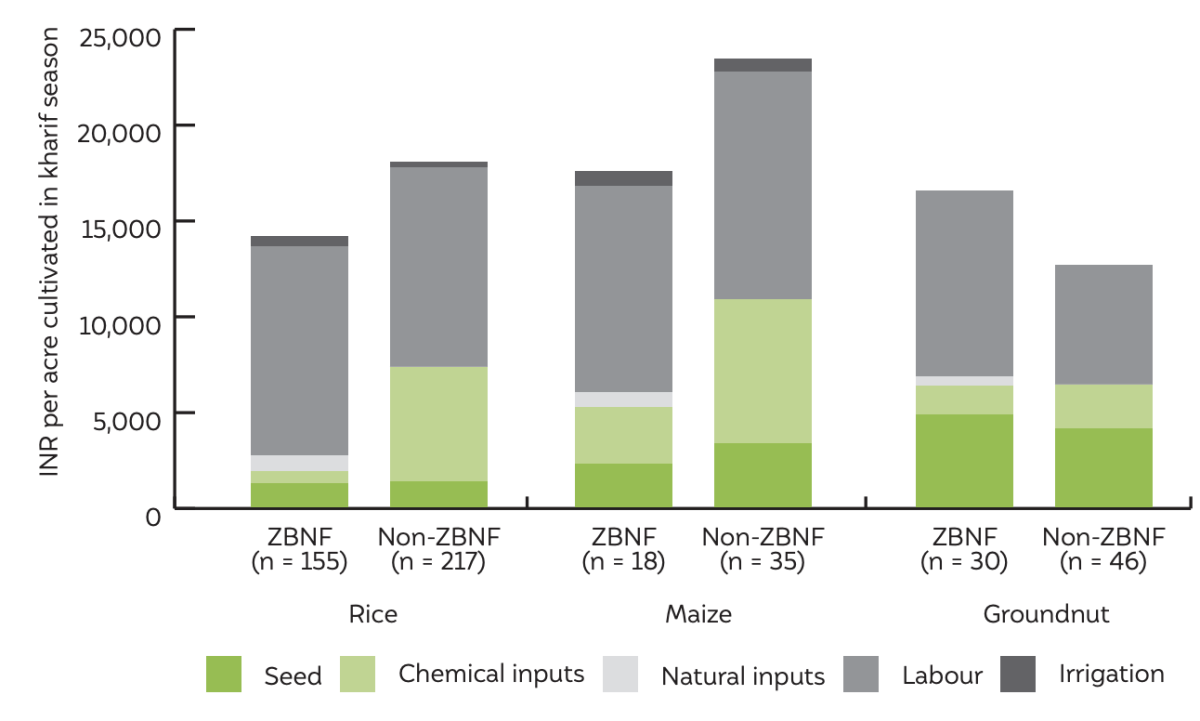

ZBNF farmers cultivating rice and maize in the Kharif season reported lower input costs per acre as compared to their non-ZBNF peers. Most of the savings were driven by dissimilarities in the expenditure on fertilisers and pesticides. ZBNF cohort growing rice reported the median cost per acre at INR 12,200 (mean: INR 13,918) whereas that for the non-ZBNF cohort was INR 14,700 (mean: INR 15,580). For maize cultivators, the median expenditure per acre for ZBNF farmers was INR 15,660 (mean: INR 15,925), while that for non-ZBNF farmers was INR 17,425 (mean: INR 19,812). The per acre input cost of ZBNF farmers cultivating groundnut was however higher than that of non-ZBNF farmers, in contrast to rice and maize. The median cost of groundnut cultivation per acre for the ZBNF cohort was INR 12,483 (mean: INR 15,964) as compared to the median of INR 9,996 (mean: INR 11,952) for the non-ZBNF group.

ES3: Average input cost drops significantly for ZBNF rice and maize farmers mainly because of savings from avoided use of chemical fertiliser and pesticides

Source: Authors’ analysis

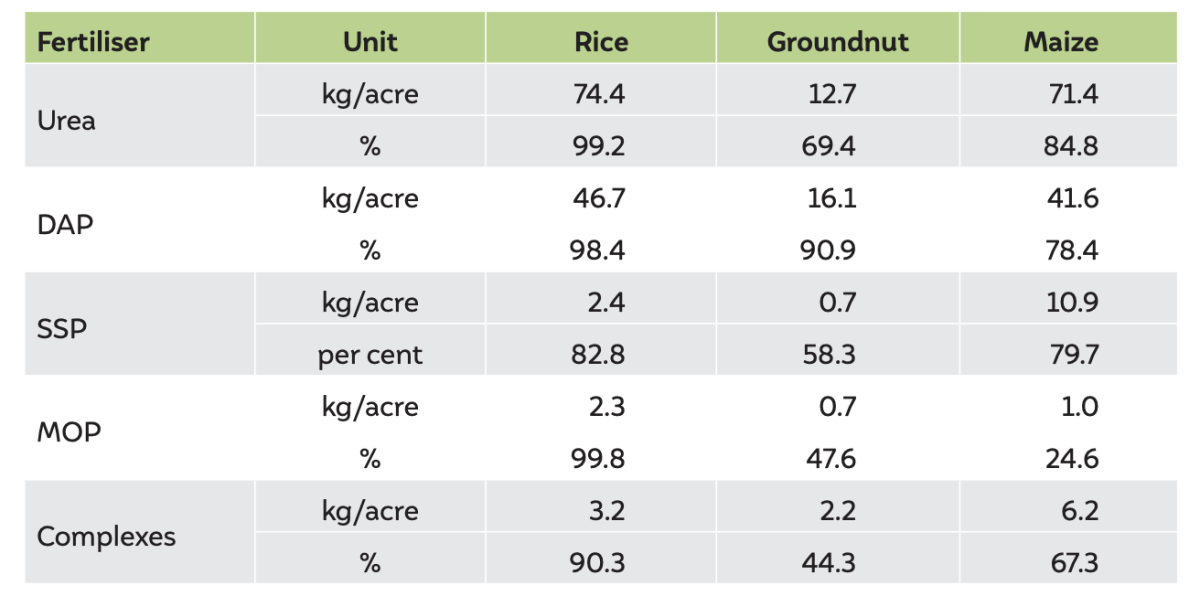

Using econometric analysis, we estimate the potential savings in the consumption of fertiliser subsidies if ZBNF were to be scaled up in Andhra Pradesh. We found that on average, non-ZBNF farmers used three times more urea and DAP per acre than ZBNF farmers. We also found considerable variations in the use of fertiliser across crops. While rice and maize farmers used more urea per acre than those growing other crops, groundnut farmers applied much less of each fertiliser.

To calculate the difference in expected fertiliser, use between the ZBNF and non-ZBNF cohorts, we used the crop-specific binary variables and crop–ZBNF interaction variables in the model. For instance, the expected urea use for ZBNF rice farmers is 0.59 kilograms per acre (kg/acre) and for non-ZBNF farmers is 74.46 kg/acre, resulting in 73.87 kg/acre of avoided urea consumption. The avoided fertiliser consumption due to ZBNF varied from 83–99 per cent for various fertilisers in rice. For groundnut, we found a reduction of almost 70 per cent in urea and 91 per cent in DAP, due to ZBNF.

ES4: Fertiliser consumption of non-ZBNF farmers (in kg/acre) and avoided fertiliser consumption due to ZBNF (percentage)

Source: Authors’ analysis

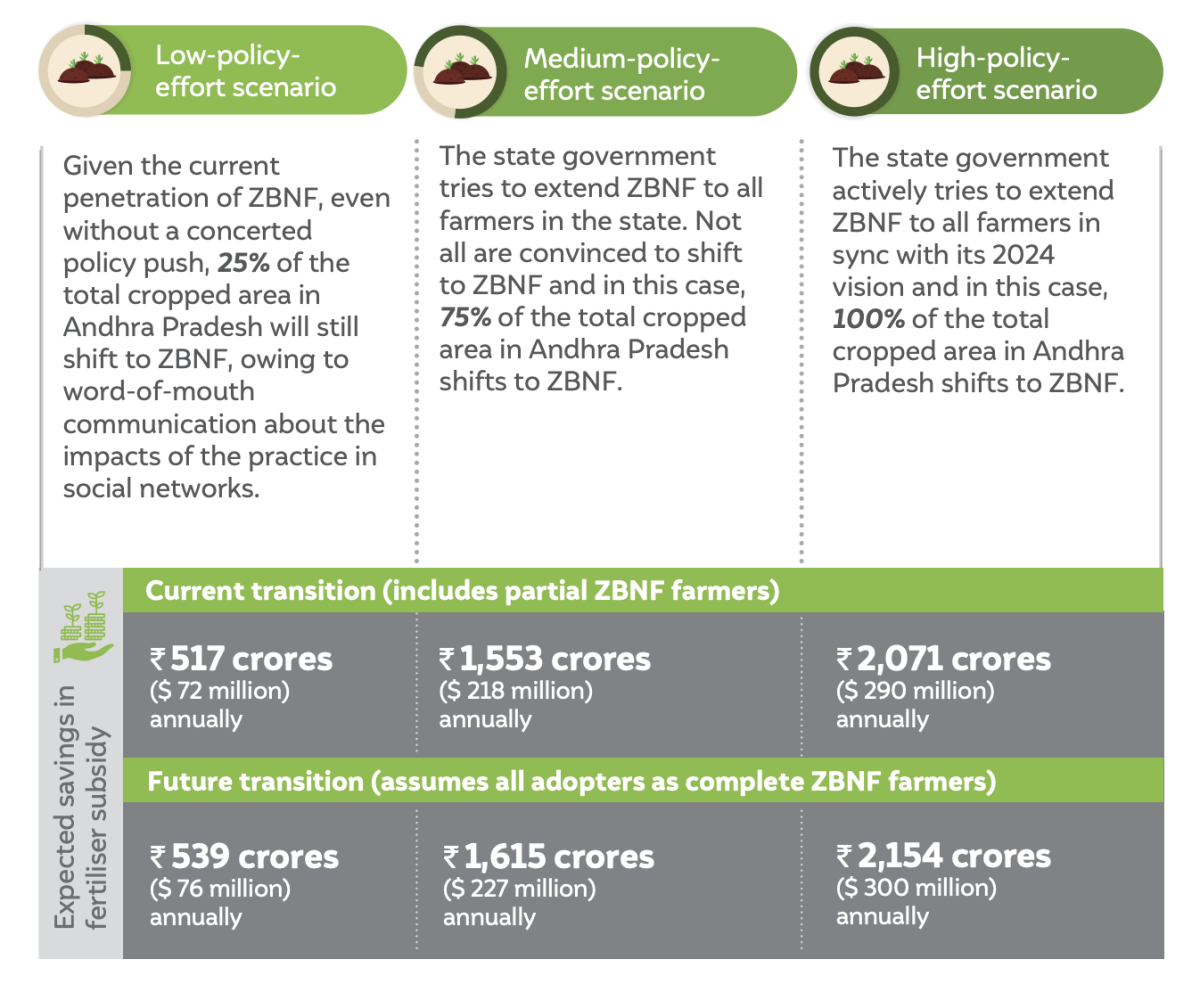

We estimated the savings in fertiliser subsidies in Andhra Pradesh in three policy scenarios: (1) a low -policy-effort scenario where 25 per cent of the total cropped area in Andhra Pradesh shifts to ZBNF; (2) a medium-policy-effort scenario, where 75 per cent of the total cropped area in Andhra Pradesh shifts to ZBNF; and (3) a high-policy-effort scenario, where the government’s effort is able to implement ZBNF in 100 per cent of the cropped area in Andhra Pradesh.

Based on the actual reported consumption of fertilisers in our survey, if no one in Andhra would have been practising ZBNF, the annual subsidy outlay would have been about 2,154 crores (USD 300 million). Against this counterfactual, we estimate fertiliser subsidy savings worth INR 517 crore (USD 72 million) annually on account of ZBNF penetration in a lowpolicy scenario and INR 1,553 crore (USD 218 million) annually in a medium policy scenario, with the bulk of the savings resulting from the avoidance of the subsidy on urea. In a high policy effort scenario, we expect subsidy savings worth INR 2,071 crores (USD 290 million) annually. which is almost 96 per cent of the subsidy outlay under the counterfactual scenario (zero penetration of ZBNF). This estimation reflects the current ground realities where some of ZBNF farmers are still using some level of chemical inputs.

We also estimated the potential savings in fertiliser subsidies considering the same three scenarios but assuming a complete transition of the adopters. We find that in a low policy effort scenario, fertiliser subsidy savings worth INR 539 crore (USD 76 million) annually could be expected. In a high policy scenario, we expect subsidy savings worth INR 2,154 crore annually (USD 300 million) – a 100 per cent savings against the counterfactual scenario.

It is worth noting that our estimated fertiliser subsidy outlay in the counterfactual scenario, i.e. INR 2,154 crores is only about 60 per cent of the actual subsidy outlay for Andhra Pradesh for the years 2017-18. The difference in subsidies based on actual consumption and the sales records of manufacturers could likely be because of the leakages in the current subsidised fertilisers’ administration mechanism. The nearly 40 per cent difference between the two figures is slightly lower than the 65 per cent of leakage in fertiliser subsidies estimated by the Government of India (2017).

While this study establishes the fertiliser savings potential with the scaling-up of ZBNF, we need further rigorous evidence to understand ZBNF’s impact on improving crops’ climate resilience, the soil health, local biodiversity, and water-use in agriculture. When scaled up, ZBNF could significantly reduce fertiliser requirement and consequently the fiscal allocation for fertiliser subsidies, while potentially ensuring chemical-free food to billions of Indians across the country

Agriculture is at the heart of the discourse on employment, economic growth, and food security in India. There is now increasing recognition that Indian agriculture needs to reduce its dependence on chemical fertilisers and adopt sustainable practices to take into account the full costs and impacts of existing production practices. In Andhra Pradesh, as part of a state government-led initiative, ZBNF practices have been extended to 500,000 farmers. The vision to extend ZBNF to all six million farmers and eight million hectares of cultivable land in the state by 2024 is ambitious but timely. Andhra Pradesh’s leadership has had a decisive impact on the central government’s strategy to promote sustainable agricultural practices across the country, with the prime minister having recommended the scaling up of ZBNF across the country while addressing the 14th Conference of Parties (COP14) to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD). It is therefore critical that evidence of the process and the impacts of ZBNF be generated, not only in Andhra Pradesh, but in other regions and agro-climatic zones as well.

Case studies on ZBNF have documented the experience of ZBNF farmers who transitioned from conventional practices. While some studies reported positive outcomes in terms of reduced input costs and improved yield and farm income, further data and research is needed to validate these outcomes (S.Galab, et al. 2019). This study contributes to a growing evidence base by gathering insights from a survey of about 600 farmers across all agroclimactic zones in Andhra Pradesh, and captures the potential for reduction in fertiliser consumption by ZBNF and non-ZBNF farmer cohorts.

We find that ZBNF farmers are growing more fruits and vegetables as their main kharif crop compared to their counterparts. Such a shift at scale could alter the relative production of various crops and at the same time could contribute towards more balanced diet of farmers and nutritional security for farmers and consumers. We find significantly lower fertiliser consumption (>95 per cent in most instances) in the ZBNF cohort than in the non-ZBNF cohort of farmers. The reduction in urea application in rice cultivation due to ZBNF practices is most notable, at 74 kg/acre. This could mean a dramatic reduction in the reliance on fertiliser subsidies if the practice were scaled up nationally. In the national context, if the transition to ZBNF happens at scale, we will have dramatic annual savings of thousands of crores of rupees (a 75 per cent transition to ZBNF in Andhra Pradesh alone is expected to reduce subsidy outflow by INR ~1,600 crore/USD 225 million). Andhra Pradesh with its vision to roll out ZBNF to the entire state could save ~ INR 2,100 crore/USD 295 million annually in fertiliser subsidies.

Indian agriculture is in the need of a ‘shake-up’, giving the surmounting agrarian crisis, growing water-stress, and stagnating yields despite growing chemical-inputs. Policies to promote ZBNF are yielding encouraging results for farmers in Andhra Pradesh. The sustained scale-up of ZBNF across the country may need state-level leadership in a manner similar to that in Andhra Pradesh. Changing cultivation practices to ZBNF could potentially eliminate the growing burden of fertiliser subsidies while extending chemical-free food to consumers.

Policy Study on Re-calibrating Institutions for Climate Action

Millet Mantra - The Culinary Centrepiece of India's G20 Presidency

How to Design Scalable and Sustainable Programmes

Identifying Pathways for Scaling Up Climate-Smart Agriculture