Suggested citation: Rahman, Anas and Abhishek Jain. 2022. Community-Based Solar Irrigation in Chhattisgarh: Prospects and Challenges. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

This study investigates a community-owned and managed model of solar irrigation (led by women self-help groups) implemented by Professional Assistance for Development Action (PRADAN) in the Bastar district of Chhattisgarh. It aims to assess the impact of irrigation access on agricultural incomes. The study also highlights the challenges and roadblocks in scaling up the women-SHG-based community solar irrigation model and the ways to tackle them.

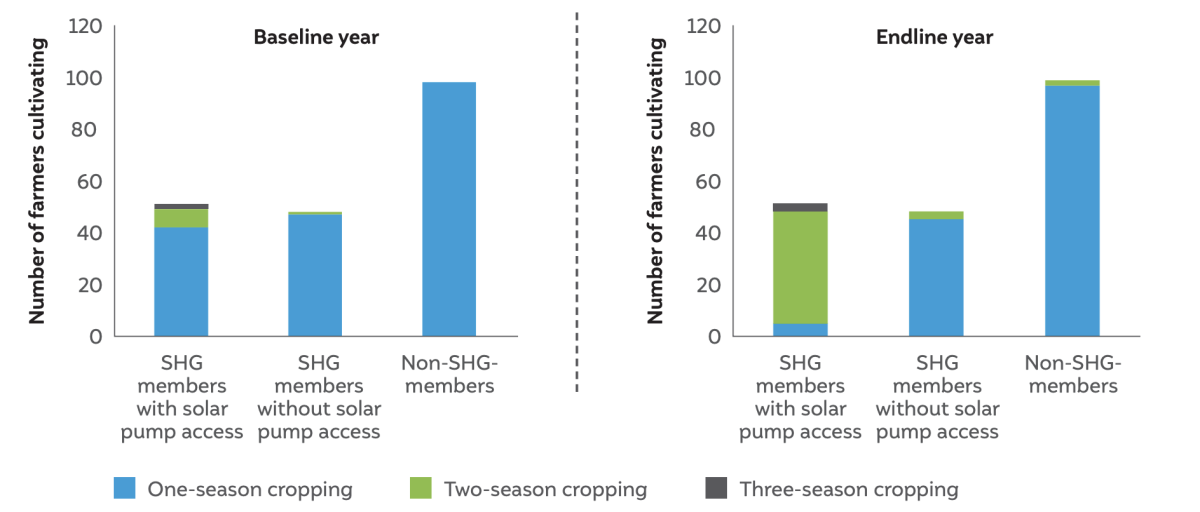

Access to solar pumps significantly improved cropping intensity among participants

Source: Authors’ analysis

Source: Authors’ analysis

Promoting solar pumping technology among marginalised and low-income farmers and scaling it up sustainably requires innovations in solar pump delivery models. In this brief, we investigate a community-owned and managed model of solar irrigation implemented by Professional Assistance for Development Action (PRADAN) in the Bastar district of Chhattisgarh.

We conducted baseline and end-line interviews as well as focus group discussions with users to evaluate the cost effectiveness and efficiency of communityowned solar pumps over a 11-month period. We found that the model is economically attractive to farmers, translating to an estimated 32 per cent increase in agricultural income for participants. In this model, the government can reach 15–20 low-income farmers with one solar pump instead of providing one subsidised pump per farmer – significantly expanding the reach of government-supported solar pumps. We also found that there is scope to reduce the subsidy by partly replacing it with self-help group (SHG) loans. We also found that starting with a lighthouse project is an effective strategy to spread awareness and set expectations. The government can replicate this strategy while scaling up the programme by setting up one project each at the block or cluster level in the first phase.

However, there are also many challenges in sustaining group-based initiatives. We found that groups based on existing social structures resolve issues better. The model included two kinds of projects – one in which a solar pump is shared within one SHG and another in which the pump is shared between the members of multiple SHGs. We found that projects where only one SHG was involved had much better cohesion and dispute resolution mechanisms than the other type. We identified multiple stress points in group cooperation, primarily arising from a lack of clear-cut rules and codification of by-laws. We propose that sustained hand holding and group capacity building is essential to tackle the challenges arising from watersharing disputes. Complementary support mechanisms like training in cultivation practices and input support can greatly augment outcomes. For the state-wise scale-up of the model, the state rural livelihood mission (SRLM) should take the leading role.

As the name suggests, ownership of a solar pump is shared by multiple farmers in such a model. The model potentially offers the following benefits:

Thus, conceptually, community-owned solar pumps can help states provide irrigation access to poor farmers while addressing groundwater exploitation concerns.

How do community-owned solar pump models fare in practice? To answer this question, we partnered with Professional Assistance for Development Action (PRADAN) to assess a pilot community-ownership model of solar pump irrigation in Bastar, Chhattisgarh. We ran an impact evaluation to assess the real-world feasibility and dynamics of the model.

The community-ownership model holds potential for expanding irrigation access through solar pumps, especially among low-income farmers. It can support groups of 5–25 farmers, depending on the size of the individual plots. With the support of government subsidies or SHG-based financing, the farmers would be able to afford irrigation at a low recurring cost. Depending on the subsidy share, the payback period can be as low as one season, and the increase in annual agriculture income can be significant.

Based on the early learnings, scaling up this model at the state level would require several steps from the state government:

Although it is an effort-intensive model for states to adopt, with the right kind of planning and investment, states could consider it to rapidly expand irrigation access within limited fiscal resources.

Enabling a Circular Economy in India’s Solar Industry

Community Solar for Advancing Power Sector Reforms and the Net-Zero Goals

Mapping India’s Residential Rooftop Solar PotentialA bottom-up assessment using primary data

Promoting the Use of LPG for Household Cooking in Developing Countries