Suggested citation: Council on Energy, Environment and Water. 2020. Energy Safety Nets: India Case Study. Vienna: Sustainable Energy for All.

This is a first-of-its-kind research to inform best practices at the intersection of energy policy and social assistance to protect very poor, vulnerable and marginalised people. A part of the the Energy Safety Nets research series, it was undertaken in partnership with Sustainable Energy for All (SEforALL), Overseas Development Institute (ODI) and the Catholic Agency for Overseas Development (CAFOD). Energy Safety Net is an umbrella term for government-led approaches to support very poor and vulnerable people to access essential modern energy services. The approach helps in closing the affordability gap between market prices and what poor customers can pay. The series and the accompanying Guide for Policymakers synthesises lessons from six country case studies from Brazil, Ghana, India, Indonesia, Kenya and Mexico, to offer recommendations for the future design of Energy Safety Nets.

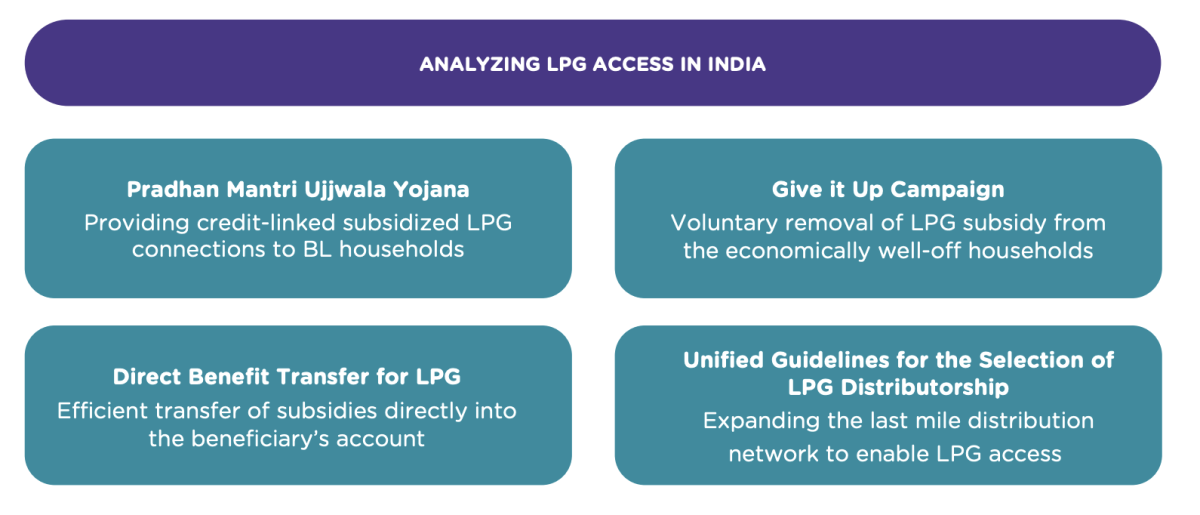

The India case study focuses on four major schemes within the ambit of LPG Programme: Pratyash Hanstantrit Labh (PaHaL) or the Direct Benefit Transfer of LPG Subsidy (DBTL), ‘Give it Up’ Campaign, Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY), and Unified Guidelines for Selection of LPG distributorships.

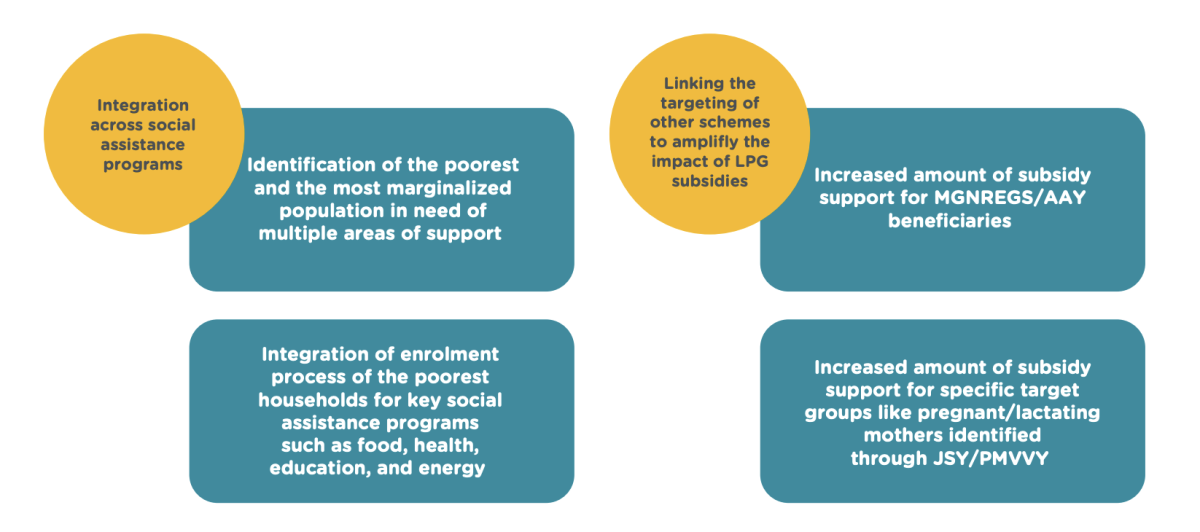

Integration and linking across existing social assistance schemes for improving access to LPG

Source: Author’s analysis

Sustainable Development Goal 7 (SDG7) aims to ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all. The idea of ‘leave no one behind’ is inherent to all the SDGs. Social protection programs are a major mechanism for ensuring access to social goods such as nutrition, healthcare, education and employment for deprived populations. In a similar context, Energy Safety Nets (ESNs) refer to social assistance mechanisms that enable poor and vulnerable people to access and use modern energy services. ESNs are a broad set of measures ranging from general energy price subsidies at one end to highly targeted social assistance at the other. The aim of this research is to identify measures that have been implemented to enable poor people to access modern energy services, analyzing their impacts and experiences, and explore the reasons for their success or lack thereof. India has experience subsidizing both access to electricity and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) for cooking; this case study focuses on the latter. In particular, it focuses on the policies and schemes introduced since 2013 to improve access to and targeting of LPG subsidies.

The Government of India primarily provides LPG subsidies to address the ill effects of combustion of biomass on maternal and child health. Since 2013, LPG subsidies have undergone many modifications to improve subsidy delivery and targeting, access to connections, and the availability of LPG. This research focuses on four major schemes within the ambit of the LPG program in India: Pratyash Hanstantrit Labh (PaHaL) or the Direct Benefit Transfer for LPG Subsidy (DBTL), the Give it Up Campaign, Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY), and Unified Guidelines for Selection of LPG distributorship.

The subsidy reforms (DBTL and Give it Up) aimed to improve the targeting of the LPG subsidy to households that need support, reduce subsidy leakage to non-domestic uses, and remove spurious connections. PMUY and Unified Guidelines for the Selection of LPG distributorship addressed the high upfront cost of an LPG connection for poor households and its unavailability in rural areas, respectively.

The schemes have achieved much of their intended impact, especially with respect to coverage of poor and marginalized households, most of which have been brought into the LPG program. As of September 2019, 80 million families had received a subsidized connection under the PMUY. Targeting of subsidized LPG was further enhanced by checks instituted under the Know Your Customer (KYC) and DBTL schemes, which had blocked 42.3 million duplicate, fake/non-existent, and inactive LPG connections from receiving the subsidy by March 2019.

Access to an LPG connection has not necessarily translated into sustained use, despite LPG refills being subsidized. For PMUY consumers, the subsidy provided on the first few cylinders was used to pay back the loan taken out to cover the unsubsidized portion of the connection. This means that PMUY consumers, who are among the poorest in India, had to pay the market price for the first few cylinders. Affordability challenges around the recurring cost of LPG for such households contributed to an average PMUY household consuming 3.4 cylinders per year against an all-India average of 6.77 in 2018. Budgeting for the relatively large initial cost is also a major concern among households with irregular or uncertain primary income from occupations such as casual labor. Additionally, there are challenges of awareness at the beneficiaries’ end regarding the receipt of subsidy.

This case study suggests that the different consumers along the spectrum of poverty may require a different amount of subsidy to make LPG use affordable. Improved targeting and rationalization of use-based subsidies could help to concentrate the subsidy on the poorest households. The Give it Up Campaign attempted to voluntarily remove the LPG subsidy from economically wellto-do households, but 90 per cent of India’s nonpoor population continue to receive it. At the other end of the income scale, the Socio Economic and Caste Census (SECC) provided a leap forward in the comprehensiveness of defining deprivation. However, using this for targeting means drawing on data obtained in 2011, overlooking changes to households’ circumstances since then, with some escaping poverty and others falling into it.

Many households’ regular use of LPG is constrained by insufficient availability of LPG and limited awareness of its benefits. To increase availability, the government instituted a tiered distribution structure that aimed to deliver LPG directly to homes or nearby collection points across India. Yet the rate of expansion in the distribution of LPG has not kept pace with the rate of connections, particularly over the last four years, which have seen a rapid increase in connections provided under PMUY. To improve awareness, during implementation of PMUY, the government started conducting LPG Panchayats, community-level platforms to facilitate interaction among new and old users of LPG (all women), educating them on the benefits of using LPG, and addressing any queries new users had with the fuel or the subsidy process. A sex-disaggregated examination of the cooking energy transition revealed that social norms mean most women lack the required means to exercise the autonomy that the PMUY scheme is trying to provide. Including the decision-makers of household expenses in awareness-raising programs is important if consumption patterns are to change.

With the dynamic nature of poverty, households are more likely to revert to the use of solid fuels for cooking if existing social assistance programs are ineffectual in providing support for regular use of clean fuel. There exists the potential to integrate and link key aspects (identification, targeting and delivery mechanisms) of different social assistance programs with the promotion of sustained use of LPG.

The Government of India implements various social assistance programs that provide targeted support for health, nutrition and education through measures that range from conditional cash transfers to subsidies. Targeting under some of the LPG programs is similar to that used in other social safety nets, i.e., they focus on the population living below the poverty line, based on SECC data. Support for the regular use of LPG could be enhanced in two ways: 1) by integrating targeting, beneficiary enrollment and delivery mechanisms across social assistance programs for the poorest population, thus reducing the administrative burden for households and the government in aggregate; and 2) by linking the identification and targeting methods across existing social assistance programs to provide a differential subsidy, i.e., enhanced support for the poorest households.

To account for the overall health impact of household air pollution in India, the government could link the existing healthcare schemes on maternal and child health with earmarked transfers for using clean cooking fuels. A precedent for this exists: other schemes such as those focusing on ensuring decent housing and sanitation have integrated beneficiaries across various social assistance programs.

The government needs to continue to improve its support for transitioning poor households away from cooking with biomass. To support a reorientation of the approach, this case study discusses potential steps to address challenges around affordability, availability, and awareness of LPG.

Recognising the poverty of the PMUY beneficiaries, the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas (MoPNG) could waive the loan or at least reduce the repayments to avoid these households having to pay the full market rate for LPG. A smaller amount (e.g. USD 0.71 or INR 50) paid over more refills would be easier for the households to afford than the current arrangement of using the entire subsidy amount to pay off the loan as quickly as possible.

Increasing the subsidy amount to cover a minimum energy threshold for all poor households would be a plausible first step to ensure sustained use of LPG. Considering the need for improved targeting, the government should adopt an approach for layered assessment. PMUY beneficiaries are an obvious first choice for an increased subsidy given their documented poverty level. To further sharpen targeting, a combination of socioeconomic factors – such as location (urban and peri-urban), social standing, education level of the primary earner of the household, age of connection, and number of refills per annum for existing connections – should be used to better identify households that should receive a reduced amount of LPG subsidy or no subsidy at all.

To deal with the high upfront cost of LPG refills paid by beneficiaries, the subsidy delivery mechanism could be changed. Instead of paying the full market price to the distributor, beneficiaries could pay the subsidized rate to the distributor with a direct debit of subsidized cylinder value transferred automatically from their bank accounts, perhaps via digital (or e-) vouchers.

Consistent and sustained awareness-raising campaigns are required to facilitate the behavioral shift to cooking with LPG and to reduce uncertainty around the LPG program. These should focus on communicating the process of subsidy calculation and disbursement for households, alongside maintaining messaging about the adverse health impacts of burning biomass. Such messages should focus on a household’s decision-maker, in addition to the primary cook.

In some areas, the government should investigate schemes that remove the option of using traditional biomass as a cooking fuel, to avoid the stacking of LPG with traditional biomass or falling back to biomass use entirely. This could involve creating opportunities for the commercial use of biomass such as bio-CNG or biomass gasification. As well as removing the potential for biomass use, such programs could also provide households with the additional income and the motivation to use LPG for cooking.

To improve distribution of LPG in rural areas, adding a component for transportation or an incentive to reward distributors who provide home delivery in hard-to-reach areas could be an effective way to improve the availability of LPG. Also, providing households in underserved areas with a back-up cylinder to account for the waiting time between running out of LPG and receiving the next cylinder would prevent them from reverting to the use of biomass temporarily.

The intra-household dynamics of decision-making may pose a barrier to use LPG for women whose labor has no perceptible economic value. Other social assistance programs focused on livelihood opportunities for women that provide them the agency to gain financial independence could be leveraged to enhance their ability to pay for LPG. Delivery of differential subsidy for LPG use could also be linked with the existing social assistance programs for maternal and child health, nutrition, and livelihoods.

Finally, several government programs now rely on the SECC database to identify and target beneficiaries. While the SECC database is effective in the identification of below poverty line (BPL) households, the administrative challenges around it should be dealt with in the next round of the national sample survey (NSS). There is a need to set clear protocols on inter-ministerial coordination, sharing of data across departments and well-defined roles for data collection, periodic updating and data management. While conceptually we have evolved in our understanding of poverty, social assistance information systems need to account for dynamic changes. This would require an independent administrative infrastructure that is focused on strengthening such a database to be used across ministries.

Energy Safety Nets (ESNs) refer to social assistance mechanisms that enable poor and vulnerable people to access and use modern energy services. ESNs are a broad set of measures ranging from general energy price subsidies at one end to highly targeted social assistance at the other. The aim of this research is to identify measures that have been implemented to enable poor people to access modern energy services, analysing their impacts and experiences, and explore the reasons for their success or lack thereof. This case study focuses on subsidization of clean cooking energy in India, in particular on the policies and schemes introduced since 2014 to improve access to and targeting of LPG subsidies.

The primary motivations behind the provision of LPG subsidies in India include addressing the ill effects of the combustion of biomass on maternal and child health. LPG policies and schemes have focused on aspects of subsidy delivery and targeting, access (to connections), and availability. Simultaneously, they have focused on inclusion and equity, along with improved efficiency. DBTL has attempted to reduce the leakage of the LPG subsidies to non-poor recipients through removal of duplicate and ghost connections and direct debit of the subsidy amount to beneficiaries’ bank accounts. PMUY has effectively targeted the most marginalized sections through SECC deprivation indicators and leveraging the targeting approaches of other schemes. The subsidized connection under PMUY has enabled 80 million households to receive an LPG connection without any upfront expenditure. Considering the gendered nature of cooking and fuelwood collection in India, PMUY has provided LPG connections in the name of the adult woman of the household and the DBTL subsidy is transferred to her bank account.

However, experience shows that access to an LPG connection does not necessarily translate into sustained use. Despite the fact that LPG subsidies constitute the largest component of MoPNG’s expenditure, the average annual LPG consumption of PMUY households is less than four cylinders, less than half of consumption by non-poor households.

Different consumers along the spectrum of poverty may require a different amount of subsidy to afford the use of LPG, and differential subsidy mechanisms along with improved targeting of subsidies could provide greater support to the poorest households. The Give it Up Campaign took the first step in sharpening the target by reducing the share of subsidies going to economically well-to-do households, yet, 90 percent of the non-poor continue to avail themselves of the LPG subsidy. An effective subsidy mechanism would adopt a targeted approach, which allocates and distributes a higher amount of subsidy to the poorest households.

In addition to affordability, the lack of availability of LPG and awareness of its benefits currently limit many households from using it regularly. The government needs to address these gaps to ensure all households use clean fuel for cooking in due course. Considering that a households’ tendency to stack fuels may depend on factors like affordability of a clean fuel like LPG, ease of access to LPG, availability of free-of-cost biomass, etc., it is important to account for these while designing subsidy and incentive mechanisms. Creating an economic opportunity for other uses of biomass would be helpful in transitioning away from the use of biomass for cooking. Generating continued awareness regarding the benefits of clean cooking fuel via LPG Panchayats has the potential to increase the use of LPG. Additionally, despite the government’s focus on women in the implementation of the schemes, intra-household decision-making with respect to purchasing LPG refills remains dominated by their spouses and other members of the household. Therefore, including the decision-makers of household expenses in awareness-raising programs is important to change consumption patterns. Ongoing campaigns educating households about the adverse health impacts of burning biomass or schemes that remove the option of using traditional biomass are required to complete a household's transition to sole use of LPG.

Considering the dynamic nature of poverty, households are more likely to revert to the use of biomass for cooking unless existing social assistance programs are effectual in providing support for regular clean fuel use. Existing large-scale social assistance programs in India offer opportunities to integrate and leverage the aspects of identification, targeting and delivery mechanisms used in other programs for the sustained use for LPG. Similar to food, education or health-focused social safety nets, the targeting approach for some policies under the LPG program has focused on the BPL population based on the SECC.

Support for use of LPG could be enhanced in two ways. Firstly, by integrating support for healthcare, education, food, energy and other essentials for the poorest parts of the population, to improve targeting and reduce the administrative burden of enrollment and delivery, both for households and for government. Secondly, by linking the identification and targeting methods across existing social assistance programs to provide differentiated subsidy to the poorest households based on their level of deprivation. For instance, integration of benefits across multiple schemes on food, health, education and energy, would reduce the burden on the households as well as the administrative burden for the ministries. While accounting for the overall health impact of household air pollution in India, the government could link existing schemes supporting maternal and child health with earmarked transfers for using clean cooking fuels. A precedent for this exists: some housing and sanitation schemes directly include and prioritize beneficiaries targeted by other social assistance schemes.

While conceptually our understanding of poverty has evolved, the social assistance information systems must also be updated to remain relevant to the realities faced by poor households. This requires an independent administrative infrastructure that is focused on strengthening a database to be used across ministries.

Enabling a Circular Economy in India’s Solar Industry

Mapping India’s Residential Rooftop Solar PotentialA bottom-up assessment using primary data

Community Solar for Advancing Power Sector Reforms and the Net-Zero Goals

Promoting the Use of LPG for Household Cooking in Developing Countries