Suggested Citation: Prasad, Sumit, Spandan Pandey, and Shikha Bhasin. 2021. Unpacking Pre-2020 Climate Commitments: Who Delivered, How Much, and How will the Gaps be Addressed? New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

The study, supported by Shakti Sustainable Energy Foundation, provides an overview of the performance of developed countries under the pre-2020 climate regime. It is first-of-its-kind research in a developing country that seeks to illustrate clearly the performance of developed countries in the Kyoto Protocol and Doha Amendment. It does so by identifying accounting concerns, and gaps in achievements vis-à-vis set targets. Based on these parameters, it sets forth a ranking framework for easy comparisons of the efforts by developed countries.

In the last few years, the discussions on climate ambition have primarily focused on either nationally determined contribution (NDC) targets committed within the framework of the Paris Agreement, or respective countries’ net-zero commitments. While these midcentury ambitions are essential for achieving the 1.5°C global warming target set in the Paris Agreement, it is equally important to study the outcomes of the emission reduction pledges made by developed countries before the Paris Agreement, in the pre-2020 climate regime. The fate of post-2020 negotiations for climate change crucially hinge upon the achievements, gaps, and issues recognised in the pre-2020 period.

However, post-2020 ambitions announced by developed countries have been set without due consideration of their past performance. Concerns continue to be expressed about the implementation of pre-2020 commitments by developing countries and were most recently emphasised in decision 1/CP.23. The issue was also discussed at the 25th Conference of Parties (COP 25) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

The significance of pre-2020 climate actions by developed countries can be broadly encapsulated across three dimensions: environmental, political, and economic.

Based on the principle of equity and common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities (CBDR-RC), the onus to reduce greenhouse gas emissions for a long time was placed on developed countries (also referred to as Annex I Parties). This principle was operationalised within the UNFCCC through two international climate agreements: the Kyoto Protocol (1997) and the Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol (2012). Both these agreements assigned quantified emission reduction targets to developed countries, based on their 1990 emission levels. Under the Kyoto Protocol, an emission reduction target of 5 per cent, based on 1990 levels, was set to be achieved by developed countries in the first commitment period (2008–2012). In contrast, under the Doha Amendment, it was agreed that an emission reduction target of at least 18 per cent would be met by developed countries in the second commitment period (2013–2020).

Research focusing on emission reductions in the pre-2020 period has been scarce. As a result, there is little clarity on the performance of developed countries under the Kyoto Protocol and the Doha Amendment. To fill this gap, CEEW has undertaken a review of mitigation outcomes for all developed countries vis-a-vis their overall commitment under the Kyoto Protocol and the Doha Amendment and the results are presented in this report. This first-of-its-kind accounting ealuation conducted in a developing country seeks to provide a clear picture of the performance of developed countries in the pre-2020 era. It does so by identifying areas of accounting concerns, gaps in achievements vis-à-vis set targets, and based on these, sets forth a framework for easy comparisons among mitigation achievements of developed countries. The key findings of our study are highlighted below.

The implementation of the Kyoto Protocol and the Doha Amendment witnessed several setbacks. Several developed countries did not participate in these climate agreement discussions. The lack of participation resulted in the Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol not coming into force for almost its entire duration (before 31 December 2020).

In the first commitment period (2008–2012), a total of 36 Annex I countries and the European Union pledged emission reduction targets. Some of the notable exceptions were the United States and Canada. Furthermore, Cyprus, Malta, and Kazakhstan were not included among Annex I countries during the first commitment period and so have been mentioned among the non-participating countries in Table ES1. In the second commitment period (2013–2020), the participation fell significantly as other large emitters like Japan and the Russian Federation did not accept the new emission reduction targets of at least 18 per cent compared to their base year levels.

Table ES1 Participation of countries in the Kyoto Protocol and the Doha Amendment

Source: UNFCCC (2021)

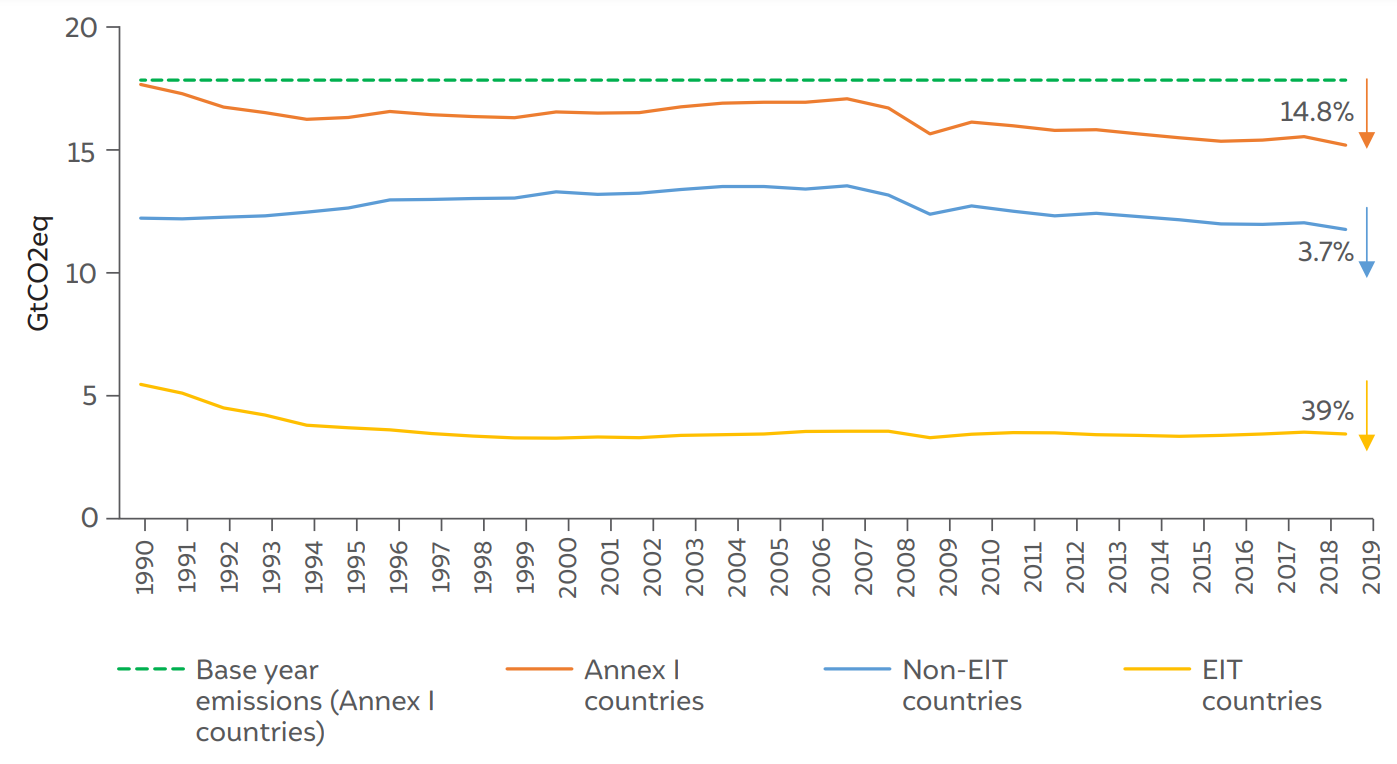

Furthermore, the countries that participated in the discussions on these two agreements also misused the existing accounting provisions to achieve their targets. The outcomes of our study provide a grim picture of the emission reductions that have been achieved by developed countries since 1990. The greenhouse gas emissions from Annex A sources for all Annex I Parties (both industrialised and economies in transition [EIT] countries) declined only by about 14.8 per cent in 2019 compared to their base year emissions levels. This reduction is quite low considering the emission reduction targets were set at a minimum of 18 per cent below the 1990 levels to be achieved by 2020 under the Doha Amendment. More dramatically, the non-EIT Annex I Parties (majorly comprising industrialised countries) witnessed a meagre emission reduction of 3.7 per cent by 2019 compared to their base year emissions levels. Thus, the 14.8 per cent emission reduction was made possible largely due to the contribution of EIT countries, which collectively showed a decline of about 39 per cent below the base year emissions levels.

The impressive 39 per cent reduction in emissions achieved by the EIT countries is not due to emission reduction measures undertaken by them but were due to the economic downturn in the 1990–1997 period, during which the emissions declined by 38 per cent. The economic shock suffered by these countries was the outcome of their transition from a centrally planned economy to a market-based economy. This led to the generation of unearned emissions allowance (equivalent to about 28.4 GtCO2eq) acquired by these countries in the 2008–2020 period. These unearned emissions allowances are also referred to as ‘hot air’, resulting from inflated base year emissions.

Figure ES1 Greenhouse gas emissions of Annex I countries without LULUCF (1990–2019)

Source: Authors’ analysis

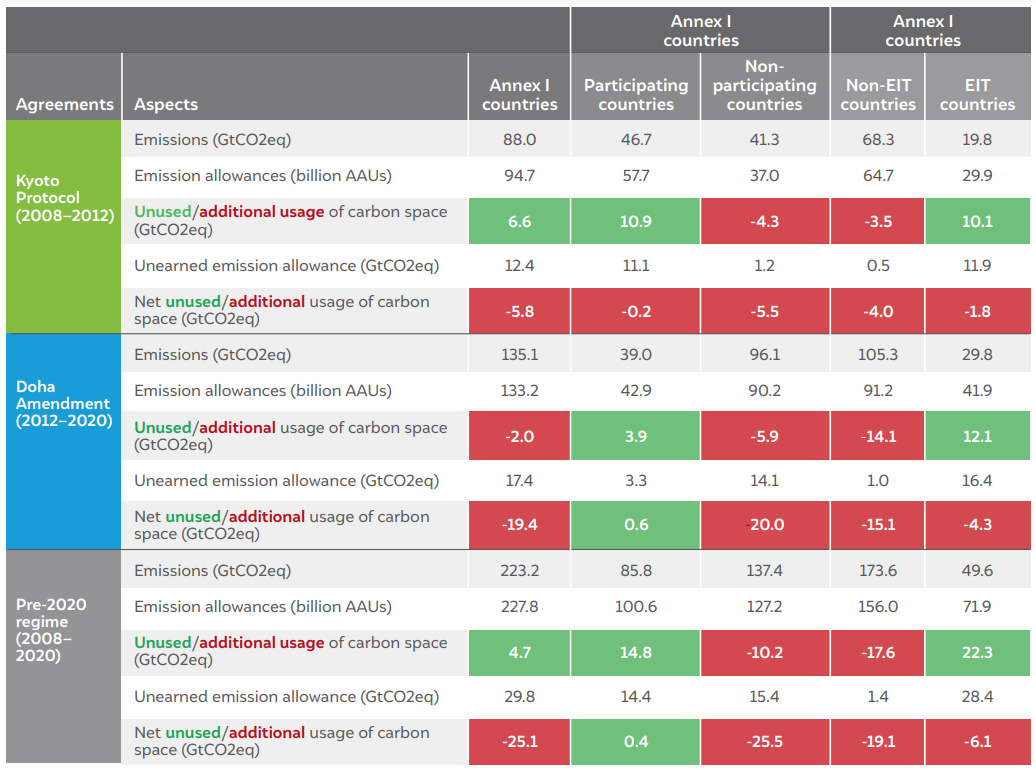

Also, the non-participation of the United States in both the commitment periods adversely affected the global climate action in more than one way. The United States emitted about 11 and 26 per cent more than their estimated emission allowance in the Kyoto Protocol and the Doha Amendment, respectively. Citing US non-participation as the reason, Canada and Japan also withdrew from the climate agreements. New Zealand and the Russian Federation also did not accept new targets in the Doha Amendment. This led to additional usage of carbon space of about 10.9 GtCO2eq by non-participating countries than their estimated emission allowance in the Kyoto Protocol and the Doha Amendment. Also, Annex A emissions from the non-participating countries represented about 47 per cent (41.3 GtCO2eq) in the first commitment period and 71 per cent (96.1 GtCO2eq) in the second commitment period of the total commitment period emissions by all developed countries.

Table ES2 Outcomes of the pre-2020 regime

Source: Authors’ analysis

In contrast, the participating countries, especially the European countries, seem to have performed well and emitted significantly less than their emission allowances in the aggregated pre-2020 period. France, Spain, Italy, and the UK collectively are estimated to have unused (left-over) emissions allowance of about 2.3 GtCO2eq by the end of 2020. And collectively, the participating countries have unused carbon space of about 14.4 GtCO2eq. However, these apparent overachievements (14.8 GtCO2eq) of the participating countries are the outcome of unearned emission allowance due to the selection of inflated base year and inclusion of deforestation emissions in their base year emissions. Australia primarily benefitted from adding deforestation emissions to its base year emissions and gained unearned emissions allowance equivalent to 1.4 GtCO2eq.

If the total unearned emissions allowance (14.4 GtCO2eq) of the participating countries is considered, then the overachievement of the participating countries in the 2008–2020 period is almost nullified. On extending these accounting criteria to the non-participating countries, it is observed that, collectively, both the participating and non-participating Annex I countries, under the Kyoto Protocol and the Doha Amendment, have emitted about 25.1 GtCO2eq more than their estimated emission allowances in the 2008–2020 period.

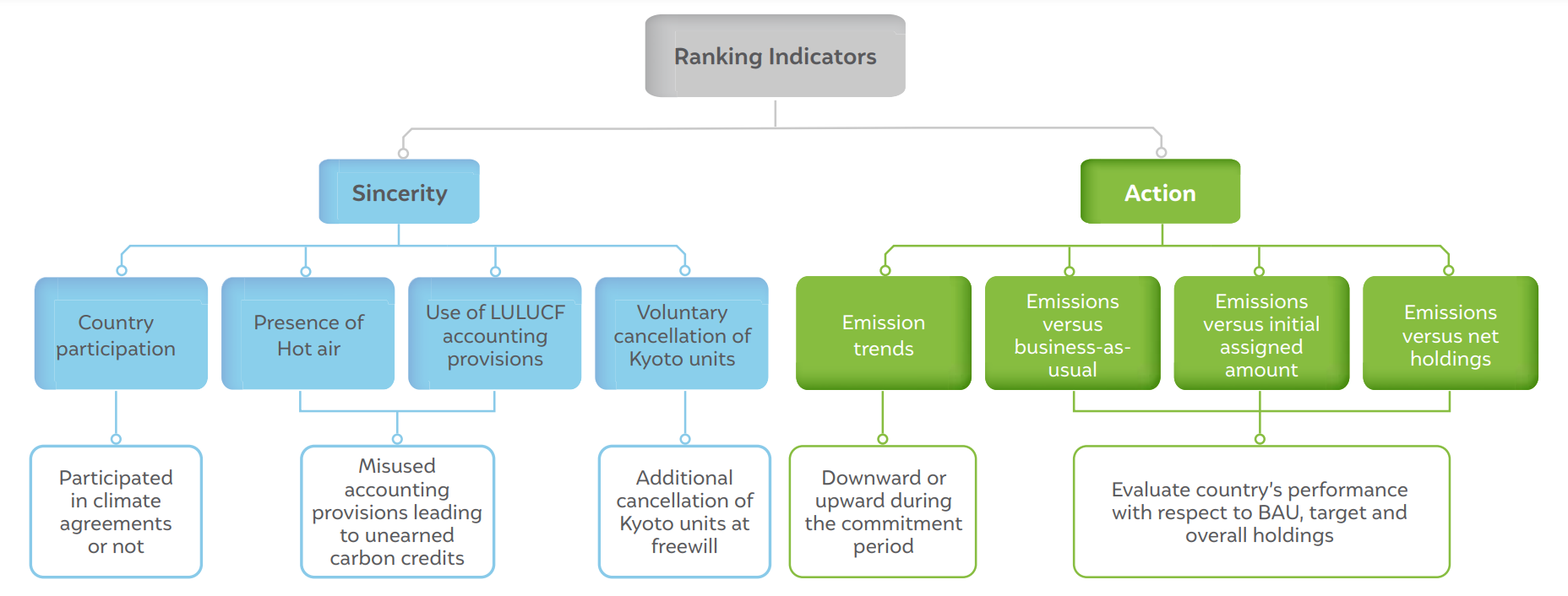

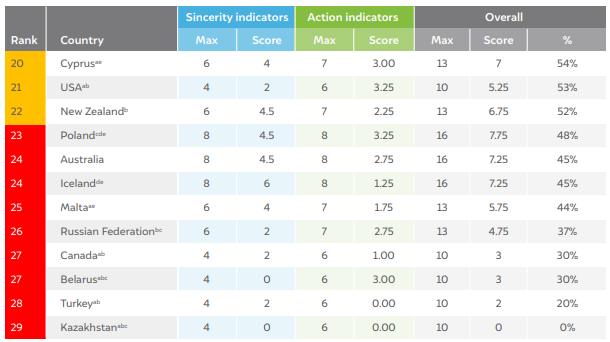

As an extension of the pre-2020 analysis, The Council has ranked all the 43 developed countries based on its sincerity and performance in mitigation efforts during the pre-2020 period. This ranking system developed by The Council is unique as it explicitly focuses on the pre-2020 climate agreements: the Kyoto Protocol and the Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol. The purpose of this ranking is threefold: (1) to provide an independent and comprehensive evaluation of the efforts undertaken by developed countries towards meeting their pre-2020 targets; (2) to enhance transparency by enabling an easy comparison of pre2020 performance among developed countries; and (3) to identify developed countries that have been climate champions in the pre-2020 period.

In order to compare their pre-2020 mitigation performances, Annex I countries were analysed and rated on their seriousness and faithfulness towards climate action (sincerity), as well as the overall mitigation performance (action) in the pre-2020 period. Figure ES2 highlights the indicators and broad categories against which Annex I countries were analysed and rated.

Figure ES2 Snapshot of ranking indicators

Source: Authors’ analysis

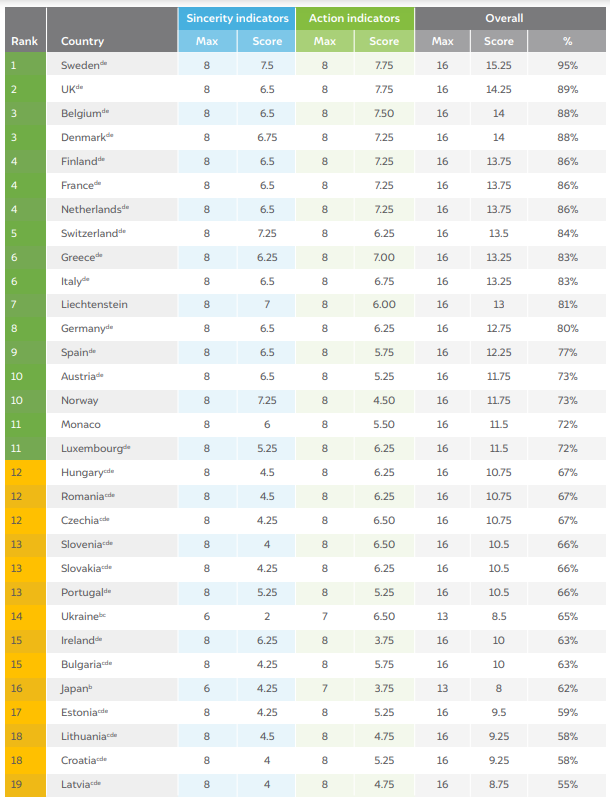

The ranking reveals that European countries have performed relatively better than non-European countries. Sweden leads the overall action indicator performance with a score of 95 per cent, followed by the UK, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, and the Netherlands. While most of the EIT countries fall in the middle of the ranking order, the non-participating developed countries are placed at the bottom. Some major economies such as the Russian Federation, Turkey, Canada, and the United States have scored around 50 per cent and less.

Table ES3 Overall pre-2020 climate action ranking

Source: Authors’ analysis

Our ranking makes it clear that developed countries have performed at various levels with respect to their emission reduction targets in the pre-2020 period. Also, the additional consumption of carbon space (25.1 GtCO2eq) is quite significant and needs to be addressed in order to limit the temperature below 1.5o C by 2100. However, the burden of these gaps emerging from the pre-2020 period should not be transferred to developing countries but distributed among developed countries themselves. Hence, the non-EIT Annex I countries, especially the non-participating countries, should consider revising or enhancing their future targets.

Another way to bridge this pre-2020 gap would be developed countries, which did not participate in the Kyoto Protocol and the Doha Amendment, purchasing the unsold certified emission reductions (CERs) and voluntarily cancel the unearned carbon emission allowance. This would be a win-win decision for both developing and developed countries because it would not only increase the demand of CERs in the sluggish market but also help developed countries comply with their pre-2020 targets without carrying them forward (post-2020 period).

Further, it is imperative to strengthen the accounting and compliance mechanism to fill the existing loopholes and ensure misuse of accounting does not occur in the post-2020 climate regimes. The accounting provisions should reflect environmental integrity and should not be curtailed at the convenience of the participating countries.

Finally, the easy exit of countries from climate agreement should be restricted as it not only results in additional burden but also undermines the trust in the process of negotiations itself and dissuades other nations from undertaking ambitious targets.

Rethinking Ocean Governance in an Era of Climate Urgency

Trust and Transparency in Climate Action

Operationalising the Loss and Damage Fund to Address Climate Impacts

Sustainability-driven Non-tariff Measures