Suggested citation: Mani, Sunil, Shalu Agrawal, Abhishek Jain and Karthik Ganesan. 2021. State of Clean Cooking Energy Access in India: Insights from the India Residential Energy Survey (IRES) 2020. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

Using data from the nationally representative India Residential Energy Consumption Survey (IRES) 2020, this study reflects on the current state of clean cooking energy access in India, the progress made over the past decade, persisting gaps, and emerging trends. The study also assesses the barriers that need to be addressed to realise the dream of smoke-free kitchens in India, and proposes various strategies that could help in making LPG affordable for the deserving beneficiaries.

As per the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019, nearly 600,000 deaths in India in 2019 can be attributed to indoor air pollution. Burning of solid fuels to prepare food on simple cook stoves (chulha) in homes exposes families, particularly women and children, to the harmful impacts of smoke and indoor air pollution (IAP). But over the past decade, India has made significant strides in replacing the use of solid fuels with clean cooking options, primarily liquified petroleum gas (LPG). One of the notable efforts has been the launch of the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY) or Ujjwala scheme in May 2016. Under Ujjwala 1.0, the Government of India distributed more than 80 million LPG connections among socioeconomically poorer households between 2016 and 2019.

Source: Authors’ analysis

Source: Authors’ analysis

Source: Authors’ analysis

Source: Yousuf Tushar

For ages, humans have used solid fuels such as firewood, dung cakes, coal and agricultural residues to cook food and derive sustenance. However, burning of solid fuels to prepare food on simple cook stoves (chulha) in households with poor ventilation exposes families, particularly women and children, to the harmful impacts of smoke and household air pollution (HAP) (Smith 2014). In India, HAP is a significant contributor to the total disease burden, accounting for nearly 600,000 deaths in 2019 (Global Burden of Disease Study 2019).

Over the past decade, India has made significant strides in replacing the use of solid fuels with clean cooking options, primarily liquified petroleum gas (LPG). The most notable of these efforts is the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY) scheme, launched in May 2016. Under the programme, the government has provided subsidised LPG connections to more than 80 million Indian households (PIB 2019). While the rapid expansion in LPG access is commendable, past research suggests that having an LPG connection does not ensure its sustained use by households. Various factors, including limited affordability, lack of timely availability of LPG cylinders, availability of free biomass, and cultural preferences propel households to stack LPG with solid fuels (Mani et al. 2020).

The absence of representative data that enables a comprehensive assessment of households’ energy choices has been a persistent concern in the discourse on energy access in India. Between 2014 and 2018, the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), in partnership with Columbia University, conducted two rounds of a multidimensional energy access survey titled Access to Clean Cooking Energy and Electricity – Survey of States (ACCESS). The ACCESS surveys covered nearly 9,000 rural households in six energy-poor states – Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal – and improved our understanding of energy access. However, a pan-India assessment of the state of cooking energy access and the barriers hindering a complete transition to clean cooking fuels has been missing so far.

In this study, we reflect on the current state of clean cooking energy access in India, the progress made over the past decade, persisting gaps, and emerging trends.

We do so with the help of the nationally-representative India Residential Energy Survey (IRES) 2020, conducted by CEEW in collaboration with the Initiative for Sustainable Energy Policy (Agrawal, Mani, Jain, and Ganesan 2020). The IRES covered 14,850 urban and rural households across 152 districts from the 21 most populous states in India. This study answers the following questions:

1. Have recent government schemes influenced LPG uptake in Indian homes, and why do gaps persist?

2. To what extent has an increase in LPG connections resulted in reduced solid fuel use in Indian kitchens, and what factors explain the continued gaps?

3. What strategies could enable sustained use of LPG among Indian households?

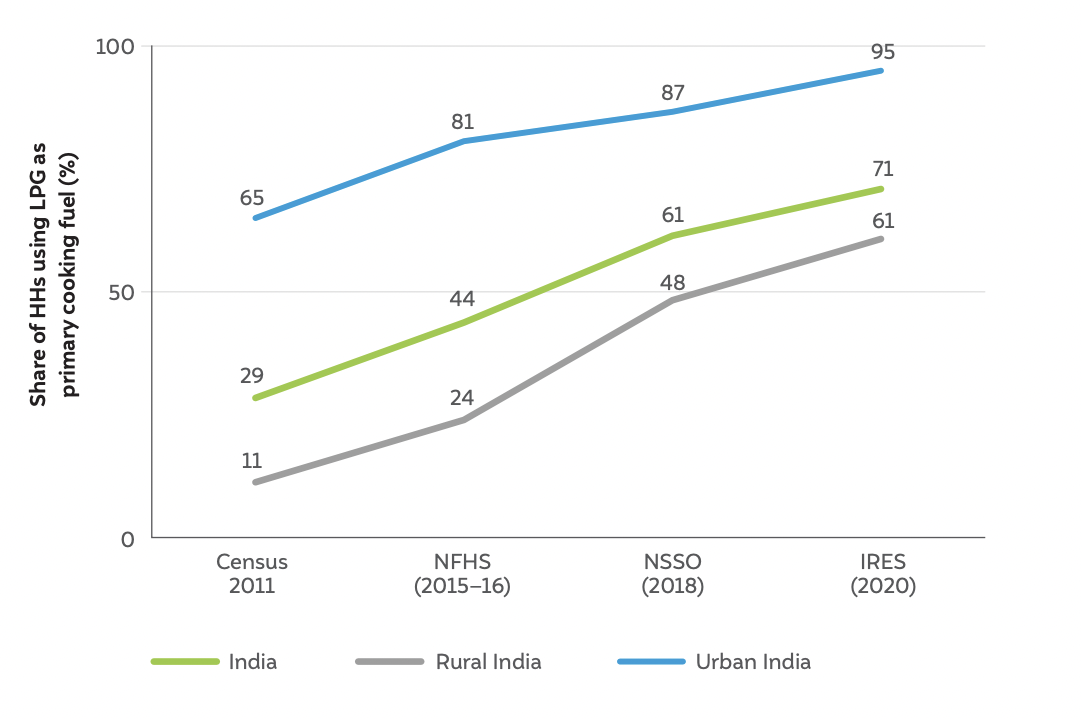

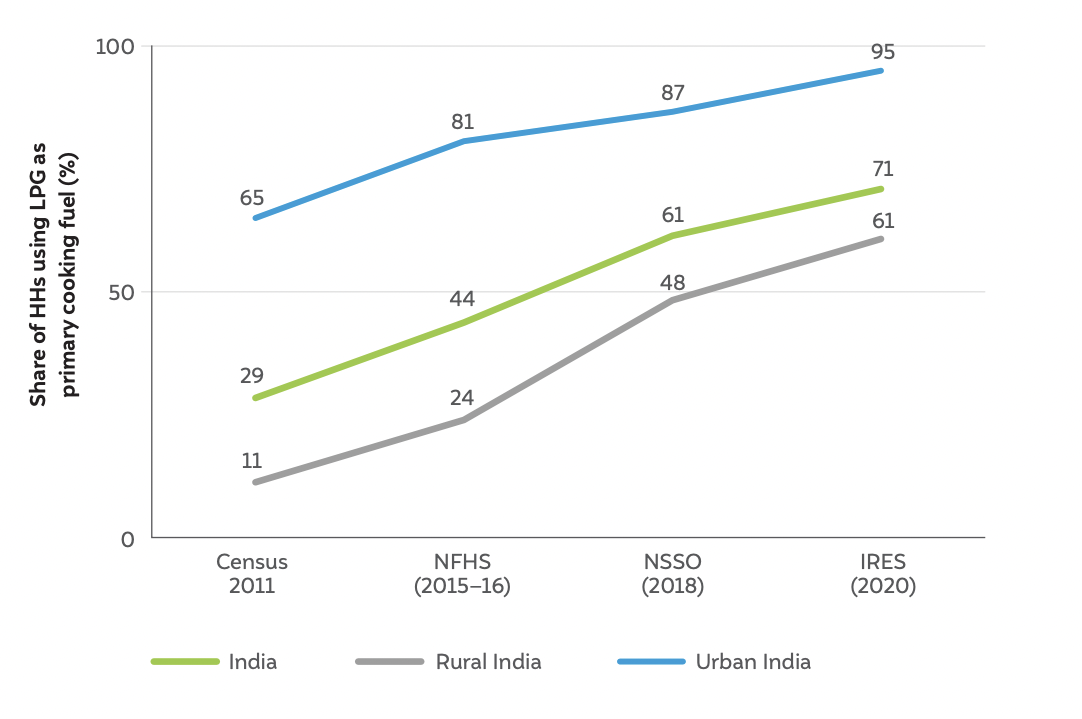

According to the IRES 2020, around 85 per cent of Indian households have access to LPG. Further, LPG’s share in primary cooking fuels increased from 28.5 per cent in 2011 to 71 per cent by March 2020 (Figure ES1). The increase in LPG use can be attributed to recent government efforts, particularly the PMUY scheme.

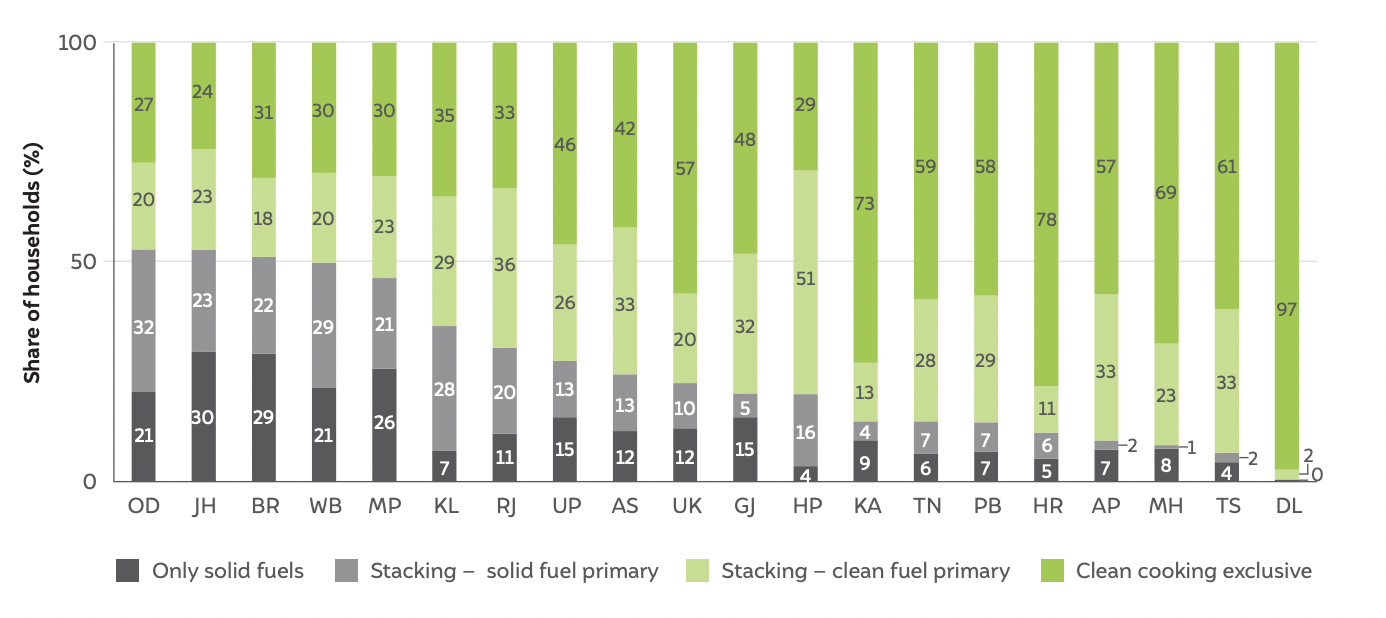

The progress in LPG use for cooking purposes is perceptible across all Indian states. However, rural areas in eastern and central Indian states like Jharkhand, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, and Odisha still have a low share of LPG primary users (possibly because of lower connection rates) (Figure ES2). Future efforts to promote clean cooking energy access must focus on these central and eastern states.

It must be noted that our estimate of 85 per cent LPG penetration is significantly lower than the government estimate of 97.5 per cent as of 1 April 2020 (PPAC 2020a). This difference is mainly because the Petroleum Planning and Analysis Cell (PPAC) estimates LPG penetration as the ratio of active domestic connections (278.7 million) to household population (285.8 million). However, it would be incorrect to equate active domestic connections with households using LPG. Despite past deduplication efforts, many households own more than one LPG connection (perhaps due to service delivery concerns) (CAG 2019).

Figure ES1 LPG use as the primary cooking fuel has more than doubled in the last decade

Source: Authors’ compilation using Census 2011; the fourth round of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4) 2015-16; 76th round of National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO-76) 2018; and IRES 2020 data

Figure ES2 Despite progress, eastern and central India have the lowest access to clean cooking energy

Source: Authors’ analysis using the fourth round of National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4) 2015–16 and IRES data

Note: PNG is a clean cooking fuel restricted to certain Indian cities, and, as per the IRES, only 0.4 per cent of all households in India use it.

Inability to afford LPG – either the connection cost or recurring expense on fuel – was the reason most cited by households (by 80 per cent non-users) for not having an LPG connection. Three-fourths of households without LPG connections earn less than INR 10,000 (USD 137) per month and live in kuchha (temporary) or semi-kuchha homes. Further, most of these households rely on labour activities as their primary source of income. Other reasons for the non-adoption of LPG include a preference for food cooked on the chulha, lack of adequate documents to procure an LPG connection, poor LPG availability in their locality, and easy availability of biomass.

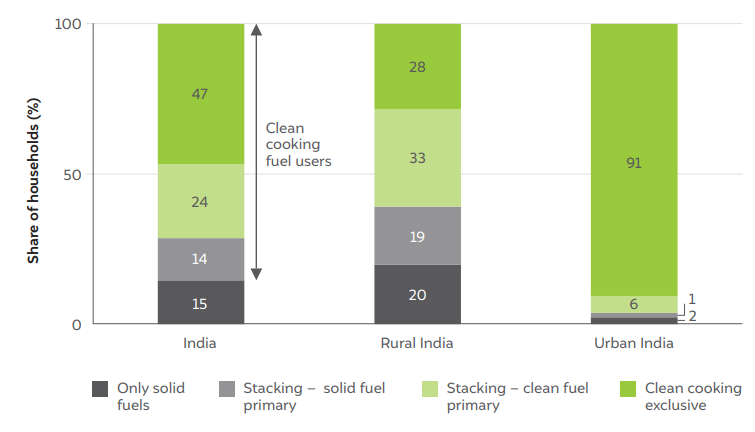

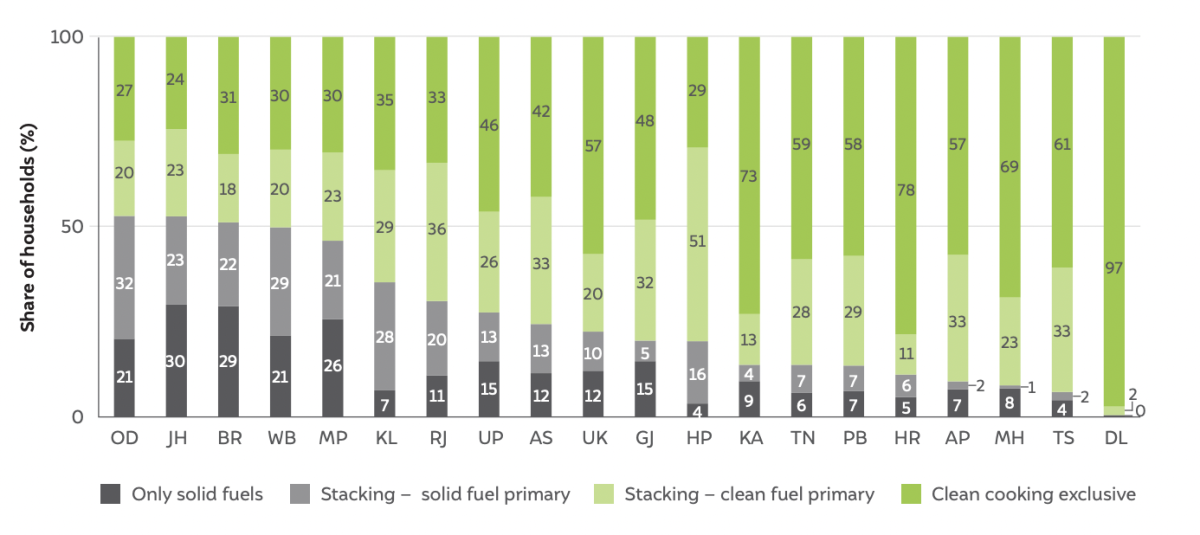

Despite improved access to LPG, 38 per cent of Indian households stacked LPG with solid fuels, mostly in rural India (Figure ES3). This underscores findings from past research that having an LPG connection does not indicate its exclusive use. Schemes and policies intended to drive clean cooking adoption need to also focus on promoting its sustained use. States like Odisha, Kerala, West Bengal, Jharkhand, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan have the highest share of households that stack LPG with solid fuels (Figure ES4).

Figure ES3 More than half of rural households in India stack LPG with solid fuels

Source: Authors’ analysis

Note: Here, clean cooking fuels refer to LPG (predominantly), electricity, and PNG.

Figure ES4 Eastern and central India have the highest levels of solid fuel use and stacking

Source: Authors’ analysis

Note: From left to right, we have arranged states in the decreasing order of the sum of the solid fuel exclusive and primary use

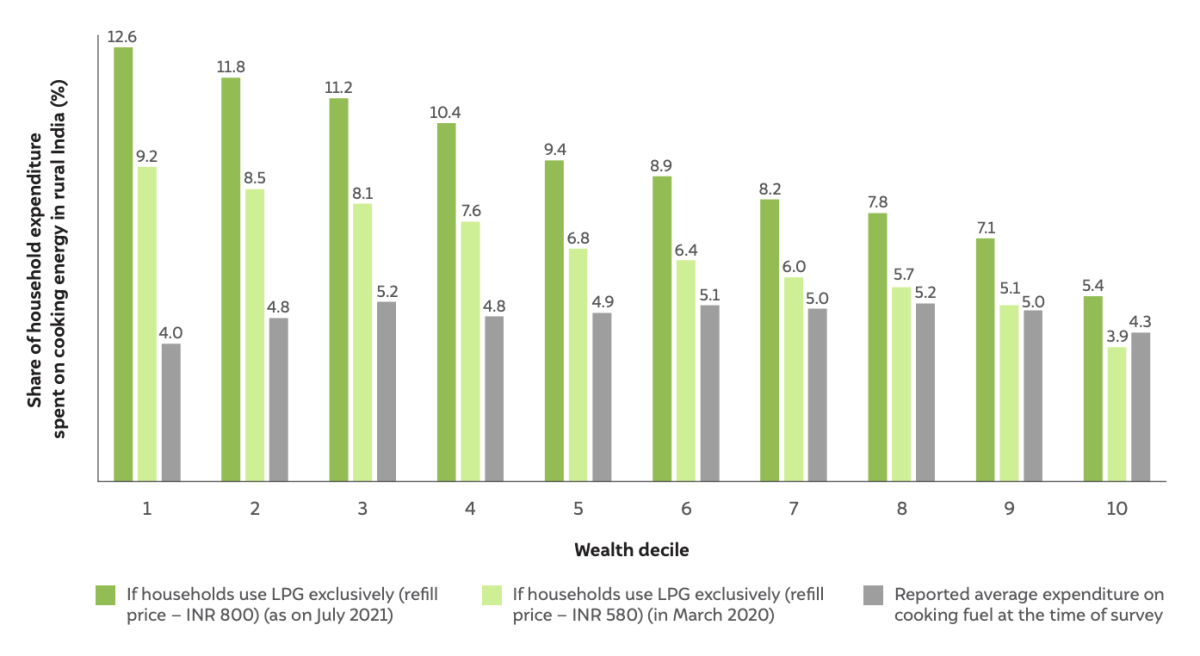

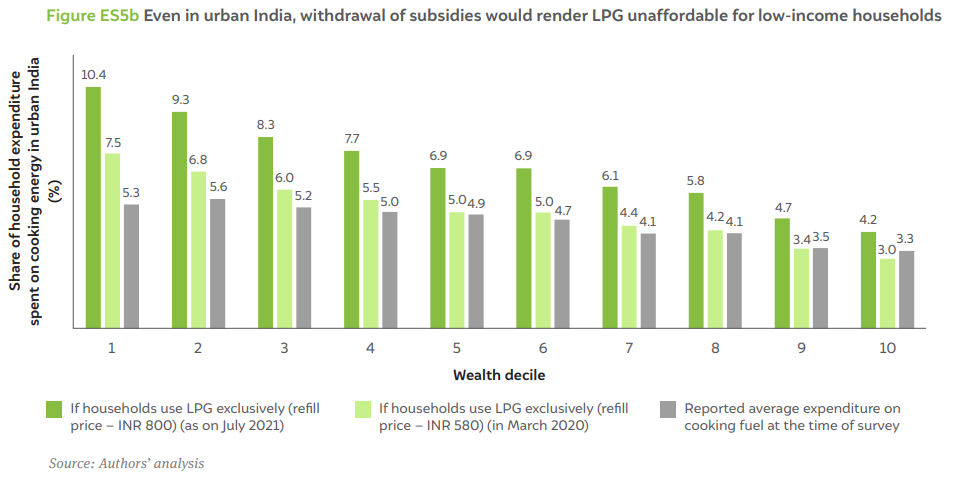

The recurring expense associated with LPG refills is the most important driver for stacking among LPG users. At the time of the IRES survey, a typical rural Indian household would have had to spend 6.7 per cent of their total monthly expenditure on LPG to use it as an exclusive cooking fuel (at a subsidised LPG refill price of INR 580 or USD 7.94).2 This is ~40 per cent higher than what rural households actually spent on cooking fuel at that time (4.9 per cent of the total monthly expenses). Further, exclusive LPG use was deemed affordable only by rural households in the topmost wealth decile (Figure ES5a).3 This partly explains why fuel stacking is a common phenomenon in rural India. In urban India, a typical household will have to spend 5.1 per cent of their overall monthly expenditure to use LPG exclusively, which is only slightly higher than their current reported expenditure on cooking fuels (4.6 per cent) (Figure ES5b).

Our assessment also indicates that after the government suspended LPG subsidies in May 2020, the affordability barrier would have become even more daunting for households. At a refill price of ~INR 800 (USD 11) as of July 2021, a typical household would have to allocate a significantly higher share of its overall monthly expenditure (9.3 per cent in rural India and 7.1 per cent in urban India) to use LPG exclusively (assuming there has been no change in household income/expenses). Combined with the drop in household incomes due to the pandemic-induced economic crisis, high LPG prices pose a risk to its sustained use, particularly among low- and middle-income households.

Figure ES5a In rural India, most households would need to significantly increase their cooking energy expenditure to transition to exclusive use of LPG

Source: Authors’ analysis

2. We assume that rural households can meet their annual cooking energy needs through seven 14.2 kg cylinders, which is also the average consumption of exclusive LPG users (in five-member households) in rural India, as per the IRES. We use the currency conversion factor of INR 73/USD.

3. To assess the long run economic status of rural households, we computed the wealth index for each household using principal component analysis based on 11 indicators spanning house characteristics and ownership of various consumer durables and motorised vehicles. Based on the relative values of this wealth index, we divided rural households into 10 wealth deciles. Refer to the technical document (http://bit.ly/IRES1) for further details.

Figure ES5b Even in urban India, withdrawal of subsidies would render LPG unaffordable for low-income households

Source: Authors’ analysis

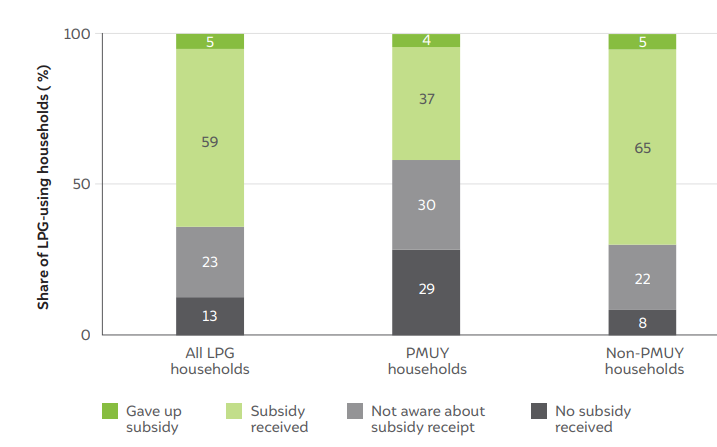

Closely related to affordability is the issue of subsidy receipt. Until the discontinuation of the LPG subsidy in 2020, the subsidy amount was credited directly to the household’s registered bank account after every refill. As per the IRES, 13 per cent of households did not receive the subsidy for their last LPG refill and 23 per cent did not know if they had received it or not. Subsidy non-receipt and lack of awareness of receipt were more pronounced among PMUY beneficiaries (59 per cent), perhaps because of ongoing loan adjustments (Figure ES6).4 However, even among non-PMUY households, a significant share – 30 per cent – of LPG users face these issues. Besides the high refill price, the lack of information or uncertainty about subsidy (receipt) could further enhance the (perceived) cost of LPG and deter households from transitioning fully to clean cooking energy.

Figure ES6 Around one-third of LPG users either did not receive a subsidy on their last refill or were not aware of it

Source: Authors’ analysis

4. Under PMUY, the government bears the LPG connection cost (~INR 1,600 or USD 22), which includes the installation cost, administrative charges, and security deposit. However, a PMUY beneficiary has to pay the remaining amount of INR 1,600 (for the LPG stove and cylinder) either upfront or through a loan from the oil marketing companies (OMCs). In case the consumer avails the loan facility, the subsidy amount for subsequent refills is first used to repay the loan. Consumers start receiving subsidy credits only after the full repayment of the loan.

Among households that stack LPG with solid fuels, the limited availability of refills is another key reason (cited by 46 per cent of them) for stacking. We found that only 64 per cent of all LPG users get their LPG refills delivered home. Urban households are more likely to get their cylinders home delivered (83 per cent) compared to rural ones (54 per cent).

In the case of households that do not have access to home delivery, members have to travel an average one-way distance of 4.9 km in rural areas and 2.4 km in urban areas to get their cylinders refilled. The average distance to be covered to procure LPG in rural areas varies significantly between states – from as low as 1.3 km in Andhra Pradesh to as much as 8.4 km in Madhya Pradesh. Barring Bihar and West Bengal, which have high population densities, almost all central and eastern Indian states have poor home delivery rates. Further, states with a higher share of newly connected or PMUY households have poorer home delivery rates, possibly because of the lower demand for refills. Low consumer density in rural areas further drives down dome delivery rates, as distributors have to travel long distances to deliver cylinders without any additional financial incentive.

We also found that nearly three-fourths of LPG users in rural areas have single bottle connections (SBCs) and only 18 per cent of them receive LPG refills on the same day. Thus, lack of home delivery combined with the prevalence of SBCs and delays in receiving LPG refills result in rural LPG users’ continued reliance on biomass

PMUY has accelerated India’s progress towards attaining multiple Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – SDG 3: Good health and well-being; SDG 5: Gender equality; SDG 7: Affordable and clean energy; SDG13: Climate change; and SDG15: Life on land/forest degradation. However, the country needs to overcome several remaining gaps to ensure universal access to clean cooking energy.

According to the IRES, 15 per cent of Indian households did not have an LPG connection as of March 2020, with unaffordability being the major barrier. The Indian government recently announced Phase 2 of PMUY in Budget 2021 to facilitate 10 million new connections (Press Trust of India 2021). PMUY 2.0 should aim to improve LPG access among the remaining households by improving the enrolment process and conducting awareness campaigns and targeted beneficiary identification. States such as Jharkhand, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, and Odisha should receive special attention, as they lag significantly behind the national average for LPG penetration.

The unaffordability of LPG refills remains the biggest barrier to its uptake as the primary or exclusive cooking fuel. Since May 2020, the government has discontinued the subsidy on LPG refills. This suspension of the subsidy, combined with the increasing market price of LPG, puts many households at risk of abandoning LPG altogether. Providing an adequate subsidy is crucial in making LPG affordable, sustaining the recent gains in LPG coverage, and weaning households away from using polluting solid fuels. We estimate that an effective price of INR 450 (~USD 6.2) per refill would bring the share of household expenditure on the exclusive use of LPG closer to the cooking energy expense borne by households at the time of the survey. However, even at this effective price, many low-income households may still find it unaffordable.

It is also important to target subsidies to deserving households given the fiscal constraints and financial burden associated with universal subsidies. Three potential approaches could be explored for targeting LPG subsidies.

However, all targeting approaches pose the risk that households no longer eligible for the subsidy may turn to procuring multiple connections or exploit other loopholes in the targeting mechanism. Thus, appropriate deduplication and delivery authentication systems would need to be implemented in parallel.

In addition to subsidy provision and targeting, the government must also run information campaigns to encourage LPG consumers to check their bank accounts for the subsidy amount and inform the bank and the LPG distributor in case of any changes in their phone numbers or bank details.

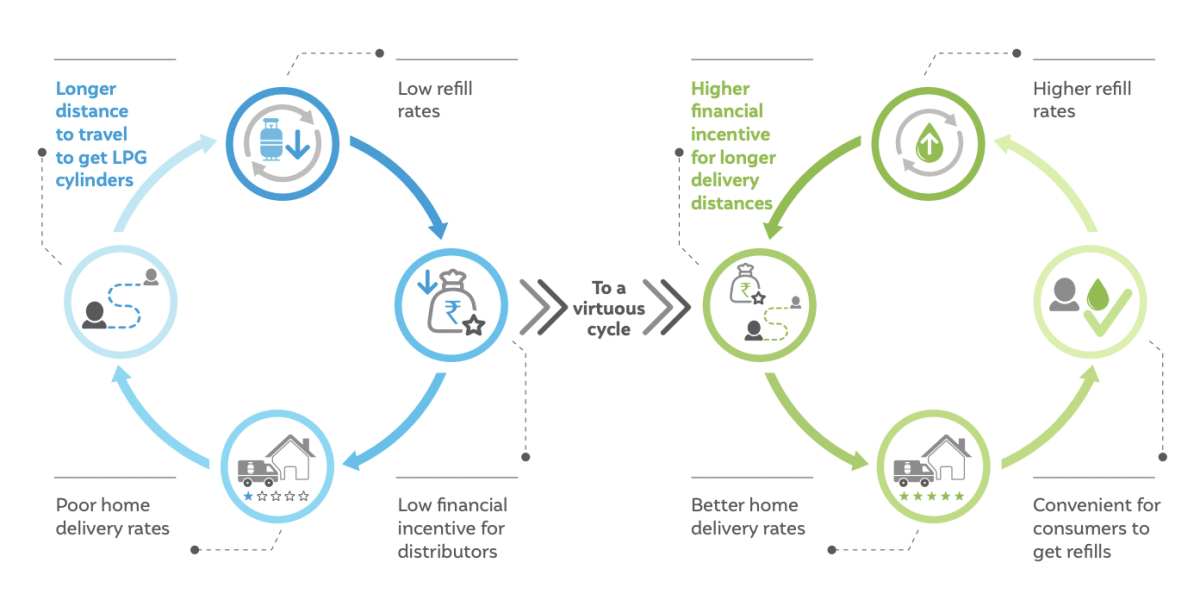

Beyond economics, availability also influences households’ adoption of LPG as the primary or exclusive cooking fuel. OMCs could leverage datasets like the IRES and identify regions where poor availability of LPG is a significant reason for biomass stacking. This would include states with a large number of PMUY households, such as Odisha, Jharkhand, and Assam. The government should also incentivise rural distributors to provide home delivery by providing a higher commission per refill, which is currently uniform across the country at INR 62 (USD 0.85) per LPG refill. Providing differential commissions linked to connection density would further improve the last-mile delivery of refills and create a virtuous cycle (Figure ES7).

Figure ES7 Linking the distributor commission with connection density would incentivise home delivery of LPG

Source: Authors’ illustration

Subsidy support for LPG may still be ineffective in face of the easy availability of the free-of-cost biomass. About 14 per cent of rural households in India rely on free-of-cost biomass exclusively, while another 50 per cent collect biomass to supplement clean fuels. Integrating the LPG programme with broader social assistance and rural development programmes would help enhance rural incomes. In addition, the government could pilot initiatives to promote decentralised biomass processing units that manufacture briquettes and pellets for industrial/commercial establishments using locally available biomass. Besides putting a monetary value to locally available biomass, this could create income opportunities for households currently gathering it for free.

Over the past decade, India has made significant strides in bridging the gaps in households’ access to clean cooking fuels. Improving LPG’s penetration among the deprived, enhancing its affordability for the needy, and boosting its availability for the hard-to-reach must remain a key priority to ensure that we completely eliminate solid fuels and the associated air pollution from Indian kitchens by 2030.

Source:CEEW

India has witnessed unprecedented progress in improving clean cooking energy access over the last decade, with households’ use of LPG as the primary fuel increasing from 29 per cent in 2011 to 71 per cent in 2020. This change can be attributed to government efforts to improve LPG availability and affordability through increased distributorships and fuel subsidies over the past decade. However, a major thrust to improve LPG access among poor and rural households, particularly in energy-poor states, came in the form of the PMUY scheme. As of March 2020, more than 85 per cent of Indian households had an LPG connection, but unaffordability still remains a major barrier for non-consumers. Thus, PMUY 2.0, announced in the Budget 2021, should target and identify the remaining vulnerable households. Also, states such as Jharkhand, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, and Odisha should receive special attention under PMUY 2.0, as they lag behind the national average for LPG penetration.

In addition to new connections, sustained use of LPG has also improved, but it is far from attaining desirable levels. About 53 per cent of Indian households rely on solid fuels for some or all of their cooking. Use of solid fuels along with LPG – fuel stacking – means continued exposure to harmful HAP despite having an LPG connection. While affordability was found to be the biggest barrier for sustained and regular use, other factors also played a role: a preference to cook a few items on a wood fire or chulha, easy availability of free-ofcost biomass, and gaps in LPG availability. Interestingly, these factors play out differently across the country: households in Haryana and Kerala cited taste preferences as the biggest reason for stacking. In comparison, in Odisha and the hilly states of Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand, easy availability of biomass trumps all other reasons. By leveraging data through large surveys such as the IRES, OMCs and the government can devise a state-specific, or still better, a district-specific, targeting approach to address key barriers.

Despite these variations in households’ reasons for stacking, affordability remains the biggest barrier to LPG adoption. For decades, the government has tried to address this challenge through recurring subsidies on LPG use. But the recent suspension of subsidies, despite the increasing market prices of LPG, puts many vulnerable households at risk of abandoning LPG altogether. Lack of reliable alternatives and habit formation over time mean that the middle to higher income groups will likely continue to use LPG despite the higher prices. However, the poor need to receive targeted support to sustain their LPG use. We estimate that an effective price of INR 450 (~USD 6.2) per refill would bring the average affordability ratio for exclusive LPG closer to the cooking energy expenditure borne by households at the time of the survey.

Considering the COVID-linked economic crisis, both the Government of India’s ability to subsidise LPG and people’s capacity to pay for non-subsidised LPG have reduced. The only way out of this will be to develop an easy-to-administer targeting approach that helps the poor continue to use clean cooking fuels without putting additional pressure on government resources.

We discuss three potential approaches for targeting LPG subsidies.

However, all the targeting approaches pose a risk that households no longer eligible for the subsidy may turn to procuring multiple connections. Thus, appropriate deduplication and delivery authentication systems would be needed.

On the other side of the affordability equation, enhancing rural incomes should also be a focus. Thus, integrating the LPG programme with broader social assistance and rural development programmes is important. The transition from biomass to LPG will free up several hours of productive time for women who can possibly leverage those hours to perform livelihood activities promoted by the livelihood missions of their respective states. Similarly, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) can provide women workers with the option of booking an LPG cylinder against three days of work. This may also address the issue of women’s lower agency in influencing LPG purchase decisions, which are otherwise usually made by the family’s male head (Jha, Patnaik, and Warrier 2021).

Subsidy support for LPG and improving household incomes may still fall short of entirely closing the gap between LPG and the free-of-cost biomass. About 14 per cent of rural households in India completely rely on free of cost biomass exclusively. Creating an opportunity cost for biomass, or an opportunity cost for the time spent procuring and preparing biomass, is imperative. Promoting decentralised biomass processing into briquettes and pellets to be used in local industrial and commercial establishments can put a monetary value to the biomass, creating a potential income for those involved in gathering it.

Beyond economics, LPG’s availability also influences its sustained use. Only 54 per cent of rural consumers receive home delivery. Those who do not receive, travel about 5 km one-way to procure the cylinder, sometimes risking their daily wages in the process. The average distance to be travelled to procure LPG also varies significantly between states: from as low as 1.3 km in Andhra Pradesh to as much as 8.4 km in Madhya Pradesh. Here, again, by leveraging datasets such as the IRES, OMCs could prioritise regions where the poor availability of LPG features as a significant reason for biomass stacking. Also, incentivising rural distributors through higher commissions to cover the disproportionately high delivery costs would help improve home delivery rates and LPG’s sustained use in rural areas.

Over the past decade, India has made significant strides in enhancing access to clean cooking fuels. Improving LPG’s penetration among the deprived, enhancing affordability for the needy, and boosting availability for the hard-to-reach must remain the government’s focus to ensure that we completely eliminate solid fuels and the associated air pollution from Indian kitchens by 2030.

Assessing Effectiveness of India’s Industrial Emission Monitoring Systems

Catalysing Local Action for Clean Air

Best Practices in CEM (Continuous Emission Monitoring)

What is Polluting India’s Air? The Need for an Official Air Pollution Emissions Database