This two-part blog series is a deep dive into the reasons behind Punjab’s farm fires. In the first part, we described what we learned from farmers in the state’s Majha region; we now turn our attention to the Malwa region, comprising high-burn districts such as Ludhiana, Barnala, and Sangrur. When we arrived here in the first week of November, vast tracts of land were yet to be harvested. As Figure 1 shows, the region’s fire count increased alarmingly as the month wore on.

Figure 1 The number of farm fires in the Malwa region (Punjab) increased rapidly in November.

Source: Authors’ analysis; NASA VIIRS 375 m; Open fires from any burning detected by satellite.

Note: We have considered fire counts between 20/09/21 and 24/09/21 from Malwa region of Punjab that includes, Firozpur, Faridkot, Muktsar, Bathinda, Moga, Mansa, Barnala, Ludhiana, Sangur, Patiala, Fatehgarh Sahib, Ropar and S.A.S. Nagar.

Farmers burn paddy stubble to clear their fields for the winter sowing season. Although machines like Happy and Super Seeders allow them to sow wheat unhindered by paddy residue, burning is often the easiest and cheapest option. But what specific challenges do farmers in the Malwa region face? What can policymakers do to tackle stubble burning? Here is what we learned.

Yield, duration, and residue: paddy variety matters

A key contributor to Malwa’s high fire count is the widespread use of PUSA 44, a long-duration, high-yield, high-residue variety of paddy. Nine of the 12 farmers we spoke with in Ludhiana and Sangrur grow PUSA 44. Two others grow it in combination with shorter-duration varieties, which mature early and give farmers the time they need for eco-friendly stubble management. PUSA 44 is popular with farmers mainly due to its yield. Charanjit Singh, a resident of Ludhiana’s Jangpur village, told us he briefly tried a short-duration variety called PR 126. But when his yield fell “by 4-5 quintals per hectare”, he went back to using PUSA 44.

Machine troubles

In Sangrur, we saw farmers using Happy and Super Seeder machines after burning their paddy residue. Diljeet Singh (name changed), a Super Seeder user, offered us an insight into why this happens. “I used [my Super Seeder] without burning [my paddy residue] last year and got very bad results. My wheat plants’ roots were not strong and were infested with pests,” he explained. Another farmer, Deepinder Singh (name changed), had a similar experience. “I use a combination of burning and the Happy Seeder, and this is the best way to do it,” he said.

A Happy Seeder and a Super Seeder being used in a field after stubble burning in Punjab’s Sangrur district.

Source: CEEW

Learnings from environmental champions

Some farmers are determined to tackle the stubble problem in an environmentally sustainable manner. For instance, Balwinder, a Jangpur resident, saves water by directly seeding his wheat crop, as opposed to transplanting seedlings from a nursery. He then uses his Super Seeder to incorporate paddy residue. “The Super Seeder has saved me the risk of fines,” he said. “I am happy to not be polluting our air. It has improved the health of my soil, so I use less water and urea.”

Raspinder Singh, a resident of Ludhiana’s Sherpur Kalan, offers another inspiring example. For four years, he has managed to persuade his father, a PUSA 44 farmer, not to burn residue. He modified his own rotavator by widening the gap between its blades to ensure that standing stubble does not get stuck in them. He said the machine has improved his soil quality and reduced water and fertiliser use. Raspinder also dedicates four acres of land to organic farming, growing sugarcane, maize and millets “with some success”.

Raspinder Singh’s brother and father demonstrate the functionality of their modified rotavator.

Source: CEEW

The way forward

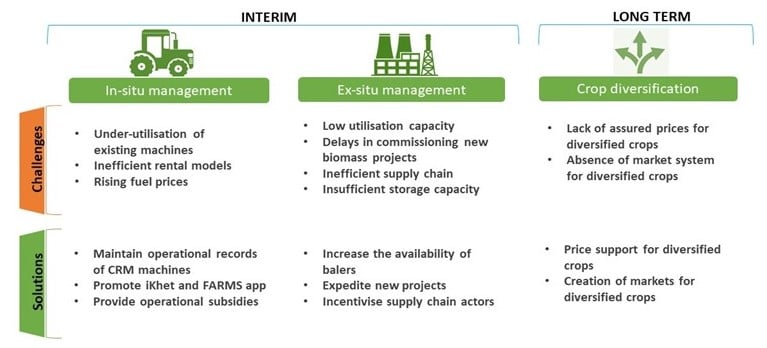

Tackling Punjab’s stubble burning problem will require a suite of interim solutions like operational subsidies for in-situ management of crop residue. It will also need a long-term strategy focusing on crop diversification. The table below lays out a policy roadmap.

Reorient government policies to end stubble burning

Source: CEEW analysis

Every farmer we spoke with in the Malwa region recognises the need for crop diversification. Paddy cultivation has not only contributed to the stubble burning problem (by generating enormous amounts of stubble and offering farmers too short a window to manage them) but has also caused a precipitous decline in Punjab’s water tables. Still, diversified crops are a difficult proposition – just ask Raspinder. “The most difficult thing is the lack of procurement,” he explained. “This leaves the entire marketing process to the farmer. Farmers are not trained to do this….[They] want quick and assured returns and diversified crops take time to sell.”

All of the farmers we spoke to believe procurement at the minimum support price (MSP) should be a prerequisite for diversification. The free market can fetch higher prices, but procurement protects farmers from price volatility. While there has been much debate on the procurement system’s feasibility, this much is clear: farmers will find it challenging to stop growing paddy without government assistance.

Our conversations with farmers over the past three weeks have shown how stubble burning is linked to broader issues of concern in Indian agriculture. Solving the problem will require a deep understanding of these linkages and significant changes in our agricultural policy framework. It will also require us to look at the problem not just through the lens of pollution in the NCR but through the farmer’s eyes too. We hope we have helped our readers do just that.

Add new comment