Suggested Citation: Kurinji, L. S, and Sankalp Kumar. 2021. Is Ex-situ Crop Residue Management a Scalable Solution to Stubble Burning? A Punjab Case Study. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

This study focuses on the ex-situ crop residue management and examines the economics of crop residue supply chain in Punjab. It compares the delivered cost of various types of biomass products such as bales, briquettes, and pellets to end-users. Further, it investigates the viability of the use of paddy residue in coal-fired power plants to supplement the use of coal in the state. The study also identifies tangible solutions to support the biomass supply chain and scale up ex-situ management in Punjab.

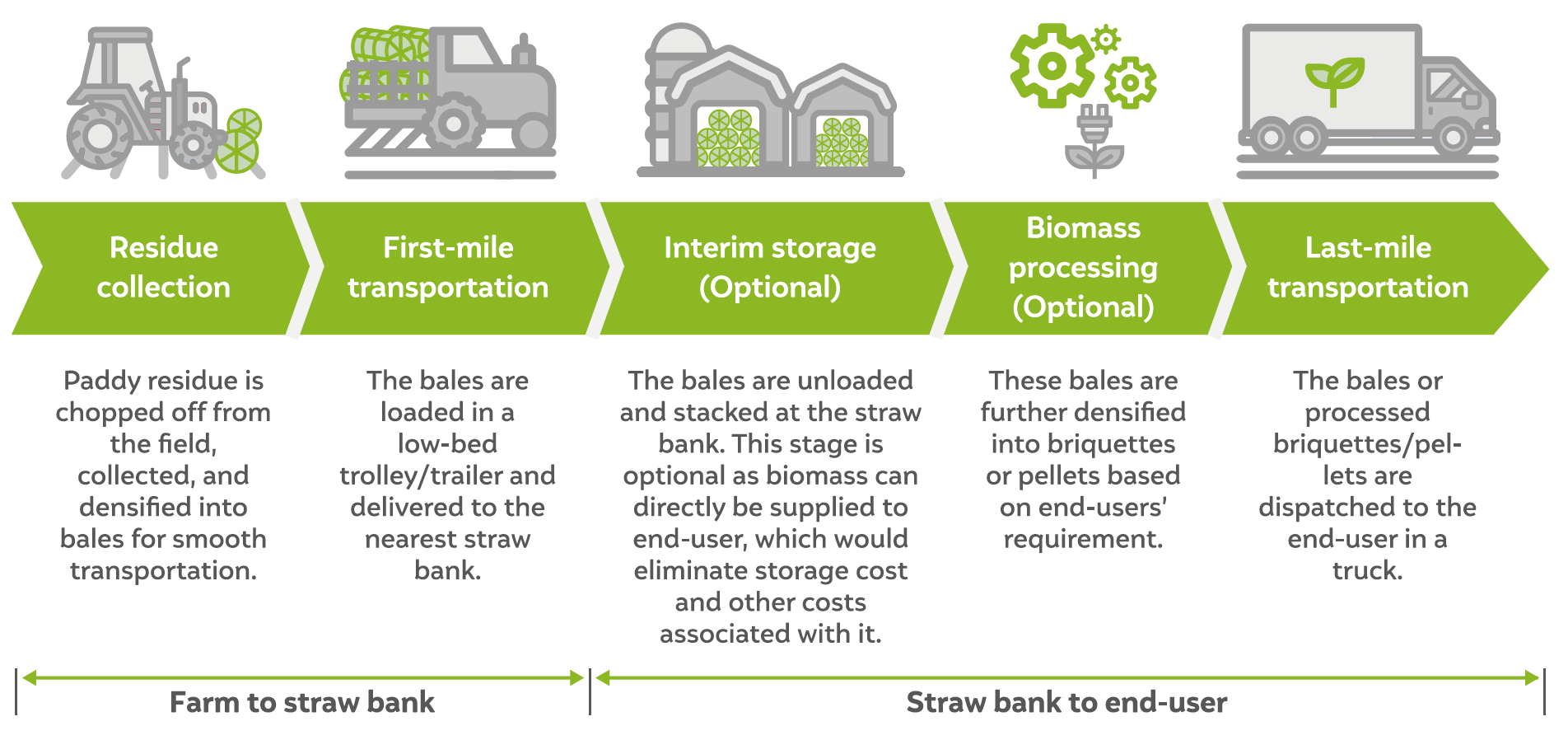

Supply chain of crop residue for ex-situ management

Source: Authors' compilation

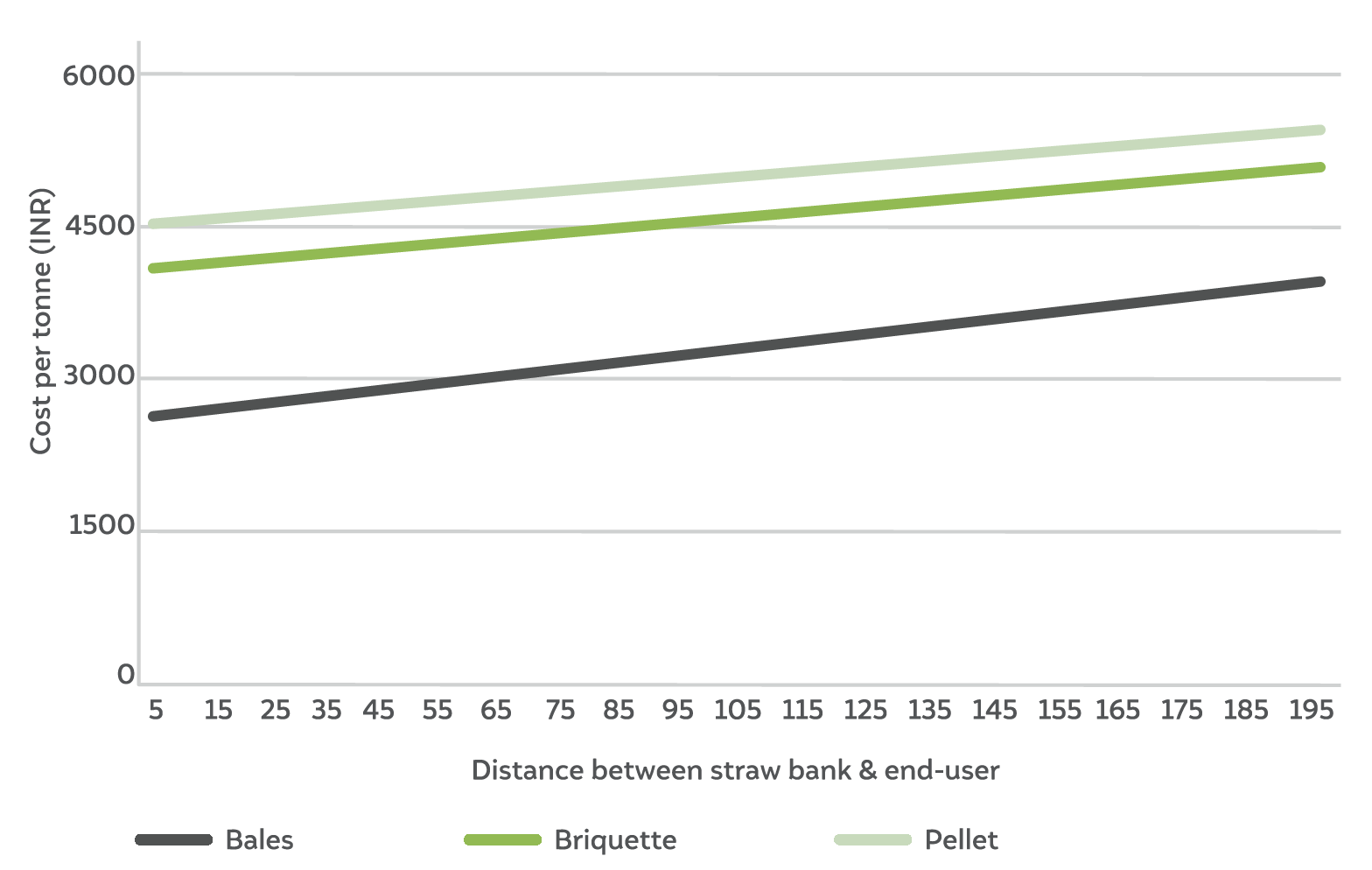

Delivered cost of biomass-based products increases with distance

Source: Authors's analysis

Agriculture and allied sectors contribute around 16.5 per cent to India’s GDP and employs nearly half of the country’s workforce (PRSIndia 2020). A massive amount of crop residue (~683 million tonnes) is generated during crop production in the net sown area of 140 million hectares across the country. While farmers use crop residue as animal fodder and for roof thatching, a significant portion (178 million tonnes) is left unused ever year (TIFAC and IARI 2018). Further, the unhealthy practice of on-farm burning of agricultural residue to clear land for the next crop, primarily in the north-western states of India, contributes to alarming levels of air pollution in the Indo-Gangetic plains.

Farmers in Punjab, where 20 million tonnes of paddy residue is generated every year during the Kharif season (Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare 2018), face an unenviable task of clearing this residue in a short window of 15–20 days. This reduced timeframe is an offshoot of the Punjab Preservation of Subsoil Act (2009), implemented to save groundwater by mandatorily postponing the transplanting of paddy from April–May to beyond 10 June (Jain 2019). In 2018, 65 per cent of paddy residue (nearly 13 million tonnes) was set on fire in the fields of Punjab, choking the air in the entire Indo-Gangetic plains (Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare 2018). The System of Air Quality and Weather Forecasting And Research (SAFAR) under the Ministry of Earth Sciences (MoES) estimated that paddy stubble burning in Punjab and Haryana contributed 40–45 per cent to Delhi’s air pollution during peak burning days in 2019 (Press Trust of India 2019).

The courts have come down heavily on stubble burning, forcing the state and central governments to initiate measures to clamp down this practice in Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh. One such effort was through the New and Renewable Sources of Energy (NRSE) policy 2019, wherein the Punjab government encourages setting up of biomass power generation units and production of biofuels (bio-compressed natural gas [CNG], bio-ethanol, and bio-diesel) using biomass (mainly rice straw) as feedstock. As of September 2020, Punjab has 11 operational biomass power plants, with an aggregate capacity of 97.5 MW, in which 0.88 million tonnes of paddy straw are consumed annually (Chaba 2020b). In 2018, the central government reported that 1.10 million tonnes of paddy residue (5.5 per cent of total residue generated) were used in various ex-situ methods such as in paper/cardboard mill and biomass power projects (Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare 2018).

Ex-situ residue management methods such as biomass power plants and biofuel projects offer an attractive option of managing the excess crop residue generated. Therefore, to ensure sustainable use of crop residue, Punjab government is inclined to sign memoranda of understanding (MoUs) with private players to set up more biomass-based projects in the state. An investment of INR 4.45 to 6 crore per MW is needed for biomass power plants (Central Electricity Regulatory Commission 2019). But due to the lack of assured biomass supply, the private sector is not finding it economically viable to invest in additional biomass plants. To ensure a reliable supply of biomass to the end-user, the Punjab government needs to create a dense network of collection centres for effective supply chain management (SCM).

Entities involved in SCM facilitate the fast clearing of residue from the field to reach the enduser. Given the voluminous nature and seasonal availability of the crop residue, its handling and on-time delivery becomes a central issue as it requires a vast workforce, heavy vehicles for logistics and extensive storage infrastructure. In addition, as crop residue has lower energy density,1 it is subjected to densification processes such as baling, briquetting, and pelletisation, which adds to the feedstock supply cost (J. Singh, Panesar, and Sharma 2010). Therefore, entrepreneurs in the supply chain find the economics of handling crop residue unattractive.

Pushed by an interest to understand the economics involved in the supply of biomass to end-users in Punjab, we undertook this study. We interviewed prominent firms involved in ex-situ SCM namely Punjab Renewable Energy Systems Private Limited, A2P Energy Solution Private Limited, Farm2Energy, and RY Energies in Punjab to chart the various steps (Table ES 1) involved and computed the delivered cost of paddy residue from the farm to the end-user. From these interviews, we have gathered insights on the delivered cost of various types of biomass products like bales, briquettes, and pellets to end-users. We further investigate the viability of the use of paddy residue in coal-fired power plants to supplement the use of coal in the state.

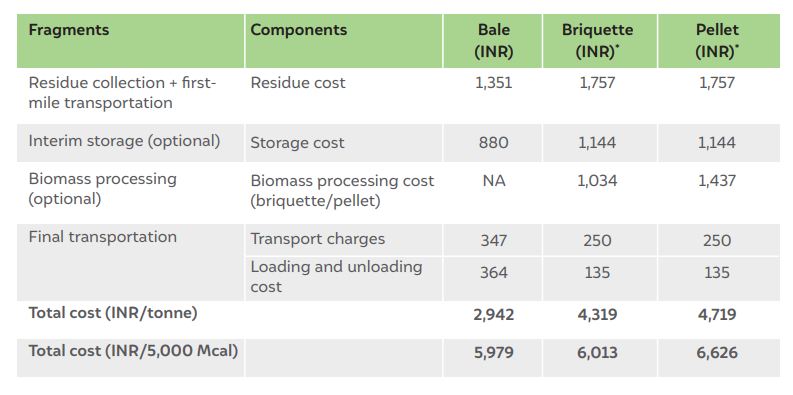

Table ES1 Supply chain of crop residue for ex-situ management

Source: Authors’ compilation

We summarise our findings on the delivered cost of paddy residue, optimum distance, and different forms of crop residue used for transit in the following. To calculate the delivered cost of biomass for the end-user, we divided the supply chain into two parts: farm to straw bank and straw bank to end-user (Table ES1).

For computing expenses incurred for residue transportation from farm to the straw bank, we consider the rental cost of machinery (such as chopper/cutter-cum-spreader, baler, and raker), labour, and fuel required for cutting and baling of paddy residue, loading and unloading cost of bales at farm and straw bank, and transportation charges for carrying bales from farm to straw bank (Table ES1).

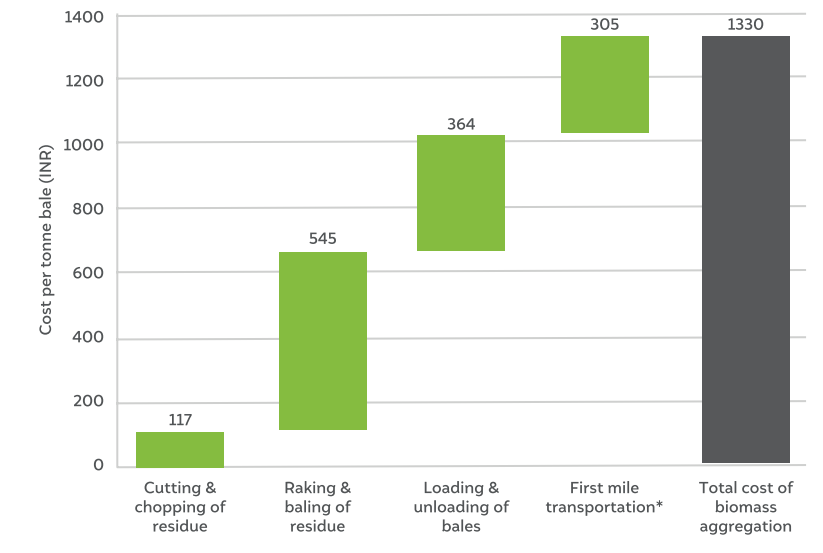

Figure ES1 Raking and baling cost is the highest in the aggregation of crop residue from farm to the straw bank

Source: Authors’ analysis

*An optimum distance of 15 km between farm and straw bank is considered.

For costs incurred to transport farm residue from straw bank to end-user, we consider biomass conversion cost (briquetting and pelleting cost), loading and unloading cost at the straw bank and end-user, respectively, and transportation charges. We take into account three forms of biomass transported to the end-user — bales, briquettes and pellets. Both briquettes and pellets can be used in boilers and stoves. But considering their different sizes, briquettes are preferred in large and medium-scale boilers, while pellets are widely used in small-sized devices, such as pellet stove, furnace, and cooking range (The AGICO 2020). As briquette and pellets are preferred over bales because of their increased energy content in industries and power plants, we also estimate and compare the delivered cost per 5,000 Mcal of bales with briquettes and pellets.

Table ES2 Delivered cost of biomass per tonne to the enduser located at a distance of 50 km

Source: Authors’ analysis

*About 1.3 tonne of residue is required to produce 1 tonne of briquette/ pellet. Additional cost of collection, transportation and storage of 0.3 tonnes of residue for every tonne of briquette and pellets has been added to briquettes and pellets resulting in the variation of collection, first mile transportation and storage cost between the three forms of biomass.

Based on our assessment and consultations with prominent stakeholders, we recommend the following strategies for better management and scaling up the ex-situ use of crop residue.

Punjab has been experiencing the problem of stubble burning for several decades, causing extensive air pollution. Needless to say, a multi-pronged strategy is needed to curb the practice. Several approaches, including in-situ treatments such as the use of Happy Seeder, mulching, composting, and ex-situ options, have been recommended to dispose of crop residue beneficially. The farmer’s choice of crop residue management depends upon the economics of the selected option, availability of implements, and the time needed for its implementation. Burning the stubble on the open field is always the easiest option for farmers. In 2018, 13 million tonnes of paddy residue (65 per cent of the total 20 million tonnes generated) were set on fire in the fields of Punjab, choking the Indo-Gangetic plains. Several experts have expressed the view that biomass-based power generation in Punjab can result in a useful consumption of crop residue as well as reduce pollution from coal-fired thermal power plants. Lack of a dense network of biomass supply chain facilities is proving to be a hurdle for scaling up ex-situ management of crop waste in the state.

Supply chain entities play a prominent role in reaching the biomass from the farmer and the end-user. Only 10 well-known SCM entities are currently involved in the supply chain business in Punjab. Developing a dense network of crop residue managing facilities could significantly reduce cost of transport. Our estimates show that transit of paddy residue in the form of bales for a distance of 5–15 km from farm to straw bank typically costs INR 1,150–1,350 per tonne. Cutting and baling of residue constitutes 55 per cent of the delivered cost of residue from farm to the straw bank. The role of supply chain entities role in providing customised farm implements needed for residue collection assumes greater importance, as individual farmers do not maintain an inventory of ex-situ farm implements.

If the state government decides to use 10 per cent of blended biomass pellets for cofiring state’s coal-fired thermal power plants, 1.47 million tonnes of paddy residue will be consumed annually in this process. Introducing a regulation mandating the minimum usage ratio of biomass derived from crop residue and stipulating a blending ratio and technical guidelines for residue usage in appropriate industries will significantly boost the demand for crop residue.

Though biomass pellets are the most demanded form of paddy residue in power plants, our estimates indicate that the delivered cost of pelleted crop residue is the highest among available options. Decentralising the sourcing of crop residue within a radius of 5–10 km of the end-user’s location would curtail the need for interim storage and drastically bring down transportation costs. Further, a clear data that maps all the end-users with their annual biomass demand would help supply chain entities to develop clear storage and logistics plans. In addition, the areas where there is a deficit in demand or potential end-users the state government can focus their in-situ management resources in that particular areas. As with increase in distance ex-situ becomes less economical, the policymakers should prioritize deployment of in-situ farm implements like Happy seeders in these locations.

Assessing Effectiveness of India’s Industrial Emission Monitoring Systems

Catalysing Local Action for Clean Air

Best Practices in CEM (Continuous Emission Monitoring)

What is Polluting India’s Air? The Need for an Official Air Pollution Emissions Database