Suggested Citation: Jha, Shaily, Sasmita Patnaik, and Rithima Warrier. 2021. Are India’s Urban Poor Using Clean Cooking Fuels? Insights from Slums in Six States. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

This brief examines access to clean cooking energy, specifically across urban slum households in six Indian states - Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh. Urban slums suffer from the double burden of pollution. They are exposed to the high ambient particulate matter pollution of cities and the household air pollution (HAP) from unclean cooking fuels. The analysis focuses on cooking fuel use patterns of households, the extent of LPG and solid fuels use, fuel stacking behaviour, and the primary cook’s perception of various cooking fuels and their impact on health. The survey covered 656 households across 83 urban slums (notified and non-notified) spread across 58 districts. The study, however, does not provide a state-level analysis because of the smaller sample size for urban slums in states such as Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh.

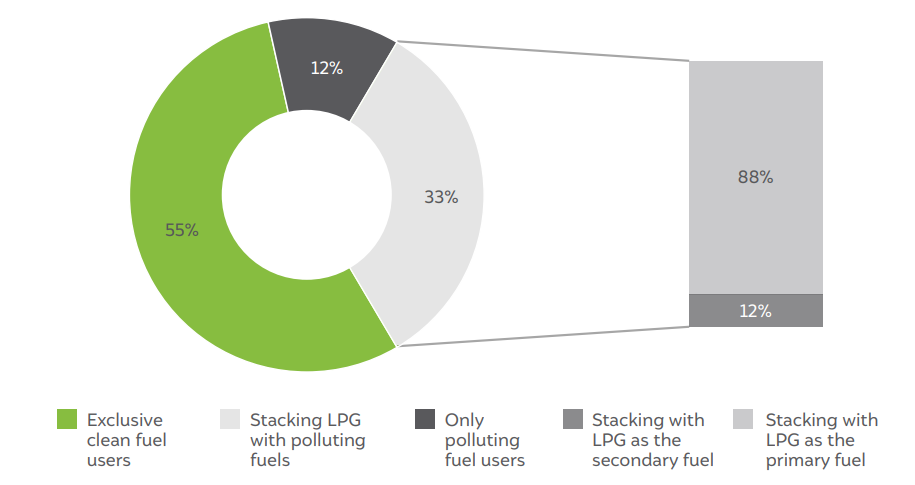

To reduce the health impacts from HAP, households who are stacking with polluting fuels would need to transition to exclusive use of clean cooking fuels

Source: Authors’ analysis

With increased urbanisation, India is experiencing acute air pollution in its urban centres. Slum dwellers are doubly affected, both by the higher concentration of particulate matter in urban areas as well as indoor air pollution from the use of unclean cooking fuels. With more than 13.7 million people living in slums in country (Census 2011), there is a strong impetus to understand the use of clean cooking fuels in such households. Existing literature on energy access and use in slums across developing countries assume that energy infrastructure is available in these settlements as they are situated in urban environments (Butera et al. 2016). Household air pollution (HAP) has an estimated average contribution of 30–50 per cent to ambient air quality across India’s urban and rural areas (Balakrishnan et al. 2019). Addressing biomass burning for cooking, water heating, and space heating during the winters has the potential to help reach the national ambient air quality standards (Chowdhury et al. 2019).

However, our analysis shows that a large share of these households do not have access to clean fuels due to lack of afforability or patchy supply. In this brief, we discuss access to clean cooking energy in urban slums across six states (Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Chhattisgarh). These states have a low socio-demographic index and a high disease burden due to air pollution (Balakrishnan et al. 2019). The findings of this brief are based on a primary survey conducted in rural areas and urban slums in these states – Cooking Energy Access Survey 20201. The analysis focuses on the fuel use patterns of households, the extent of use of LPG and solid fuels, fuel stacking behaviour, and the primary cook’s perception of various cooking fuels and their health impacts.

Slum households vary widely in their use of clean cooking fuels. Therefore, to understand their cooking energy use patterns better, we categorised these households into three groups:

*In this brief, the use of clean cooking fuels is considered synonymous to use of LPG.

1. This has been referred as ‘our survey’ thereafter.

Figure ES1 To reduce the health impacts from household air pollution (HAP), households that are stacking with polluting fuels will need to transition to exclusive use of clean cooking fuels

Source: Authors’ analysi

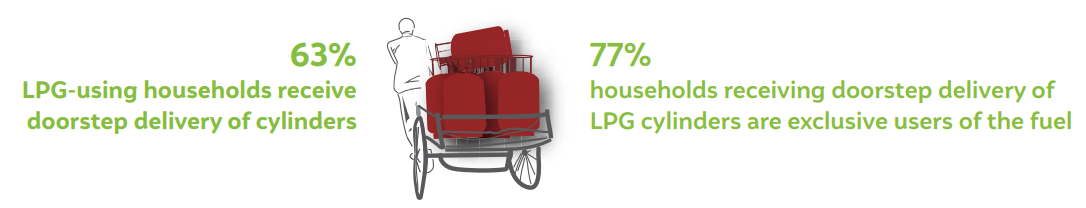

While most urban slum households have an LPG connection, exclusive use of LPG is limited to just over half of the total households. The household’s economic status (measured through asset ownership) and their access to doorstep delivery of LPG refills are two critical factors that determine their ability to use LPG exclusively. We found that households with higher asset ownership have significantly higher odds of using LPG as an exclusive fuel.

Although schemes like Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY) have helped increase LPG adoption, this has not resulted in the complete replacement of biomass-based fuels. Despite 86 per cent of households having an LPG connection, the data shows that over a third of slum households are stacking with polluting fuels (including firewood, dung cakes, agriculture residue, charcoal, and kerosene). Most of these households use polluting fuels daily or at least weekly, which increases their exposure to household air pollution.

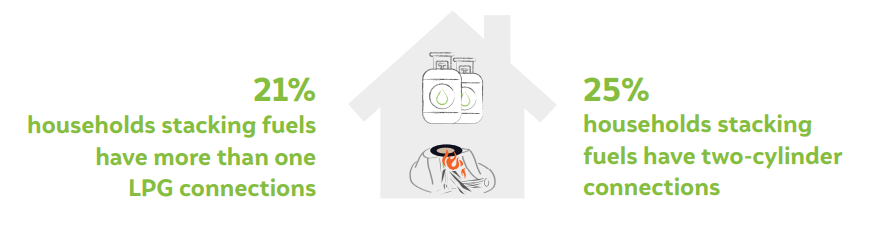

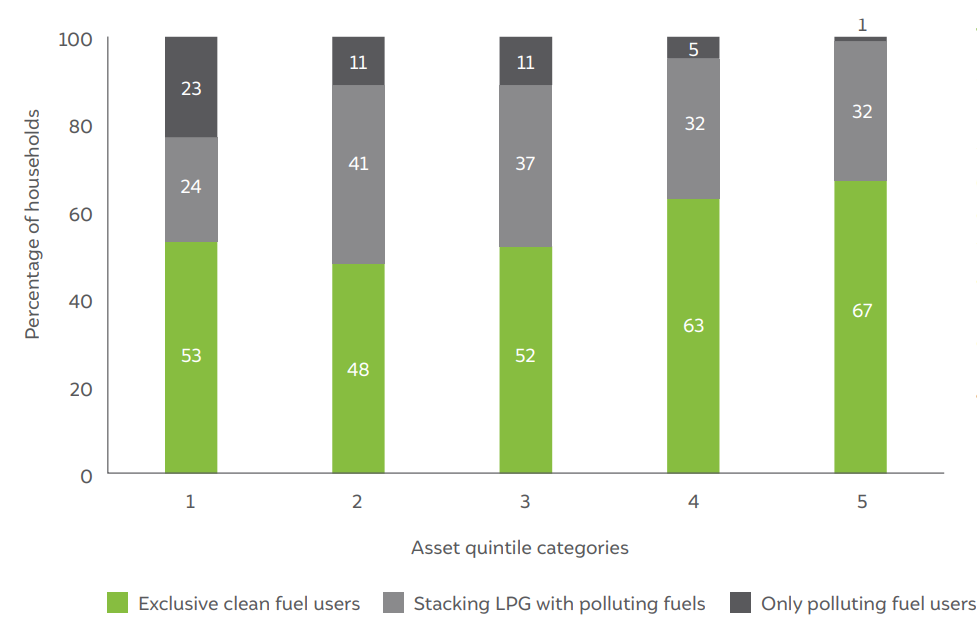

Among the households stacking LPG with polluting fuels, the reasons for stacking vary: affordability, free-of-cost availability of biomass, seasonality, and taste preferences. Across asset quintiles, we find that stacking is highest among the middle categories (second and third quintile), though most households in these categories have adopted LPG. Still, the affordability of the fuel remains a significant concern. One-fourth of households who are stacking polluting fuels have a median annual refill rate of eight cylinders and above (same as exclusive LPG users), despite having a similar household size as those using LPG exclusively. Most of such households fall in the wealthiest asset quintiles and use a chulha (mud stove) for cooking chapatis or vegetables, suggesting that they are not necessarily using unclean fuels due to the unaffordability of LPG, but due to other factors like taste.

Figure ES2 While stacking is highest among the middle categories (second and third quintile), it is prevalent across all asset quintiles, including the highest one

Source: Authors’ analysis

2.1 Non-cooking uses of polluting fuels

Despite using LPG as the primary fuel for their cooking needs, households that stack fuels use polluting fuels for non-cooking purposes like heating water for bathing (29 per cent) and space heating (10 per cent).

2.2 Seasonal variations in fuel use

Most households (88 per cent) use LPG as their primary fuel in the rainy season, while in winters, less than 45 per cent of households do so. The increased use of polluting fuels in winter could be because during these months, the polluting fuel requirement for non-cooking tasks within the household like water heating for bathing and space heating increases – which leads to the increased use of polluting fuels for cooking as well. Unfortunately, the increased use of polluting fuels in winters exposes households to the double burden of high ambient and household air pollution due to unfavourable atmospheric conditions.

Despite large-scale government initiatives like PMUY, 12 per cent of urban slum households do not use LPG and rely on polluting fuels. While most of these households are aware of PMUY, the high upfront LPG connection cost, along with the high recurring expenditure on refills, deter them from procuring an LPG connection.

Slums across the world are chronically ignored in public policy and suffer because of unauthorised and unsafe habitation without access to government services (Shahadat, Lipu, and Bhuiyan 2014). In terms of energy access, while we see a progressive change in households’ energy use patterns as we move from rural to urban, issues like affordability, availability, preference, and familiarity with the fuel and stove remain essential factors that determine households’ fuel choice.

Understanding categories of users is important for enabling access to and use of clean cooking fuels

We categorised the urban slum population based on their fuel usage patterns – using only clean fuels, stacking clean fuels with polluting fuels, and using only polluting fuels. While most households in urban slums have an LPG connection, only half of them use LPG exclusively. The household’s economic status and its access to doorstep delivery of LPG refills are two crucial factors that determine its ability to use LPG exclusively. Despite being situated in urban areas, 37 per cent of slum households do not receive home delivery of cylinders – availability is an essential factor in determining the household’s likelihood of using LPG exclusively. There is a strong impetus for the OMCs and distributors to improve their home delivery services of LPG refills in slum areas.

Stacking is prevalent in about one-third of households – there is a need for a deeper understanding of households’ preferences, fuel end-uses, and awareness. Most households reported using polluting fuels daily or at least weekly; this effectively increases their exposure to household air pollution despite having access to clean cooking fuels. Among households that stack LPG with polluting fuels, the reasons for stacking differ – affordability, seasonality, and taste preference. More than a quarter of households that stack have a similar level of LPG consumption as those that use LPG exclusively despite similar family sizes. Such households use polluting fuels not because of their inability to afford LPG. But other factors, like free-ofcost availability of biomass, taste, preference for chulha, and alternate end-uses of fuel—for instance, in space heating—influence the household’s decision to use solid fuels. Among households that stack multiple fuels, the use of polluting fuels increases during winter months; this exposes the households to a double burden of high ambient and household air pollution in these months. About 40 per cent of these households also use polluting fuels for non-cooking purposes like heating water for bathing and space heating, especially in winter.

Even with large-scale government initiatives like PMUY, we find that more than 10 per cent of urban slum households do not use LPG. They mainly rely on free-of-cost biomass for their cooking and non-cooking needs. Despite awareness of PMUY among these households, the high upfront cost of procuring an LPG connection and high recurring expenditure on refills deter them from using LPG. Evidently, there is a need to expand the reach of PMUY to cover households across slums.

Integrating the issue of lack of access to clean cooking energy within the discussion on urban poverty

This study reiterates the need to look at poverty in urban areas in the context of energy access. Given the heterogeneity of poverty in urban and semi-urban India, it is essential to understand energy poverty in the context of access to resources for an enhanced quality of life for the urban poor. Similarly, slums dwellers in large and small cities alike may experience additional challenges of access. Furthermore, not all urban poor live in slums; we know even less about the access issues of temporary residents or seasonal migrants in urban India. Therefore, in a rapidly urbanising India, studies on the urban poor and air quality need to integrate a focus on energy access to address the vulnerability of women, children, and communities to HAP and the drudgery of using polluting fuels for cooking and other household energy needs.

Converging energy access in social protection policies for the urban poor

Accounting for the vulnerabilities of the urban poor is crucial in designing and implementing policies, including social protection schemes. As a health and economic imperative, access to clean cooking energy schemes must be integrated into the social assistance programmes of other ministries (e.g., health, education, and nutrition assistance) to offer better support to slum households. This would also reduce the burden on households of claiming and accessing multiple benefits across schemes, thus freeing them to invest more time in productive activities (CEEW 2020). Government programmes such as the National Urban Livelihoods Mission and social service allocations for housing should use existing targeting approaches to include access to clean cooking energy within the ambit of services for the poor

Bringing a renewed emphasis on clean cooking energy access due to COVID-19 is essential

Most households in urban slums rely on daily wage labour or the gig economy for their household income. During the COVID-19 pandemic, these occupations have been among the worst impacted by the lockdown and the economic slowdown. A survey conducted with over 2,000 daily wage workers in urban slums during the lockdown suggests that only 7 per cent of respondents from this group received pay during the lockdown (Basu 2020), causing a massive shock to their livelihoods and wage earnings. This kind of impact pushes households into energy poverty, leading to the increased use of free-of-cost biomass and consequently increasing the risk of exposure to emissions from fuel burning. While the government has committed to supplying up to three free refills to all PMUY households under PM-Garib Kalyan Yojana, less than a quarter of households in urban slums have Ujjwala connections. The low share of PMUY households effectively makes the majority of slum households ineligible for relief support given under the PM-Garib Kalyan Yojana during the lockdown. There is a need to target vulnerable households – beyond PMUY beneficiaries – with differential subsidy support for using LPG in a sustained manner.

Increased poverty would mean increased use of polluting fuels – there is a need for a renewed emphasis on clean cooking energy access during the COVID-19 pandemic as increased use of polluting fuels has health implications (lower respiratory infections and COPD) that increase the risk of COVID-19 infections being more severe.

Assessing Effectiveness of India’s Industrial Emission Monitoring Systems

Catalysing Local Action for Clean Air

Best Practices in CEM (Continuous Emission Monitoring)

What is Polluting India’s Air? The Need for an Official Air Pollution Emissions Database