Suggested citation: Tyagi, Akanksha, Neeraj Kuldeep, and Aarushi Dave. 2020. Are Urban Microgrids Economically Feasible? A Study of Delhi’s Discom and Consumer Perspectives for BYPL. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

Urban microgrids with rooftop solar (RTS) PV and battery energy storage systems (BESS) can help power distribution companies (discoms) meet the accelerating electricity demand in cities. These may be a more convenient alternative to usual methods of procuring additional generation capacity and building new grid infrastructure. Last year, BSES Yamuna Power Limited (BYPL), in association with Panasonic India, piloted four urban microgrids in their service area.

This study employs the VGRS framework to assess the impact of these systems on BYPL revenue. It also uses a discounted cash flow method to estimate the impact on consumer finances. The analysed microgrid consists of 7 kWp RTS PV system coupled with a 10 kWh/ 5 kW lithium-ion battery. For this purpose, four scenarios were developed for the discom and consumer.

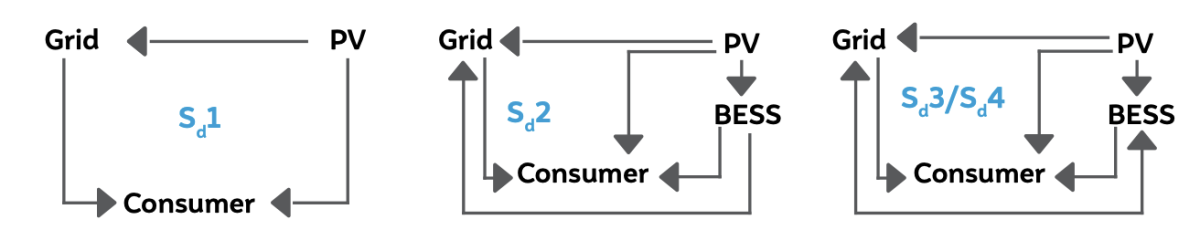

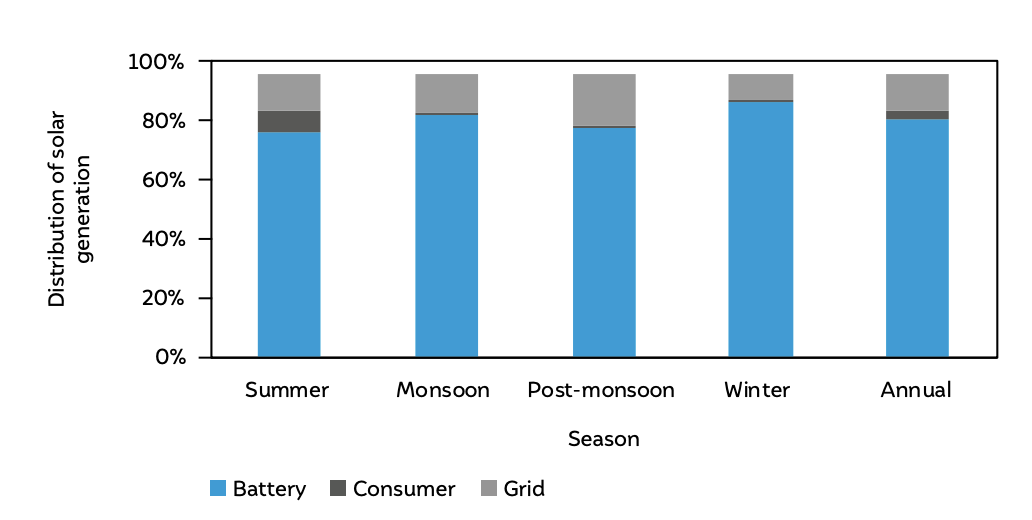

Discom scenarios:

Consumer scenarios:

Urban microgrids with rooftop photovoltaic (PV) and battery energy storage systems can help power distribution companies (discoms) meet the accelerating electricity demand in cities. These may be a more convenient, less time-consuming alternative to procuring additional generation capacity, augmenting transmission and distribution networks, and building new infrastructure. For consumers, these systems offer multiple value propositions – more reliable power supply, reduced electricity bills, and earnings from the export of stored electricity.

Solar storage microgrids could curb urban electricity woes; given the potential benefits, they offer for discoms and consumers. However, the high costs of energy storage may prove to be a deterrent. So, before installing and scaling these systems, it is necessary to understand better the impact of these systems on both the discom and consumer.

This report employs a cost–benefit analysis framework, value of grid-connected rooftop solar (VGRS) (Kuldeep, Kumaresh Ramesh, et al. 2019), to assess the economic viability of solar storage microgrids from the perspective of discoms. It also uses a discounted cash-flow analysis to estimate the financial impact on customers. These two approaches are applied to a case study of a pilot system installed by BSES Yamuna Power Limited (BYPL), a Delhi-based discom, in one of their offices. The unit consists of a 7 kWp (kilowatt peak) rooftop solar (RTS) PV system coupled with a 10 kWh (kilowatt-hour) behind-the-meter lithium ion BESS (battery energy storage system). These two components work in congruence with the grid to meet consumer demands.

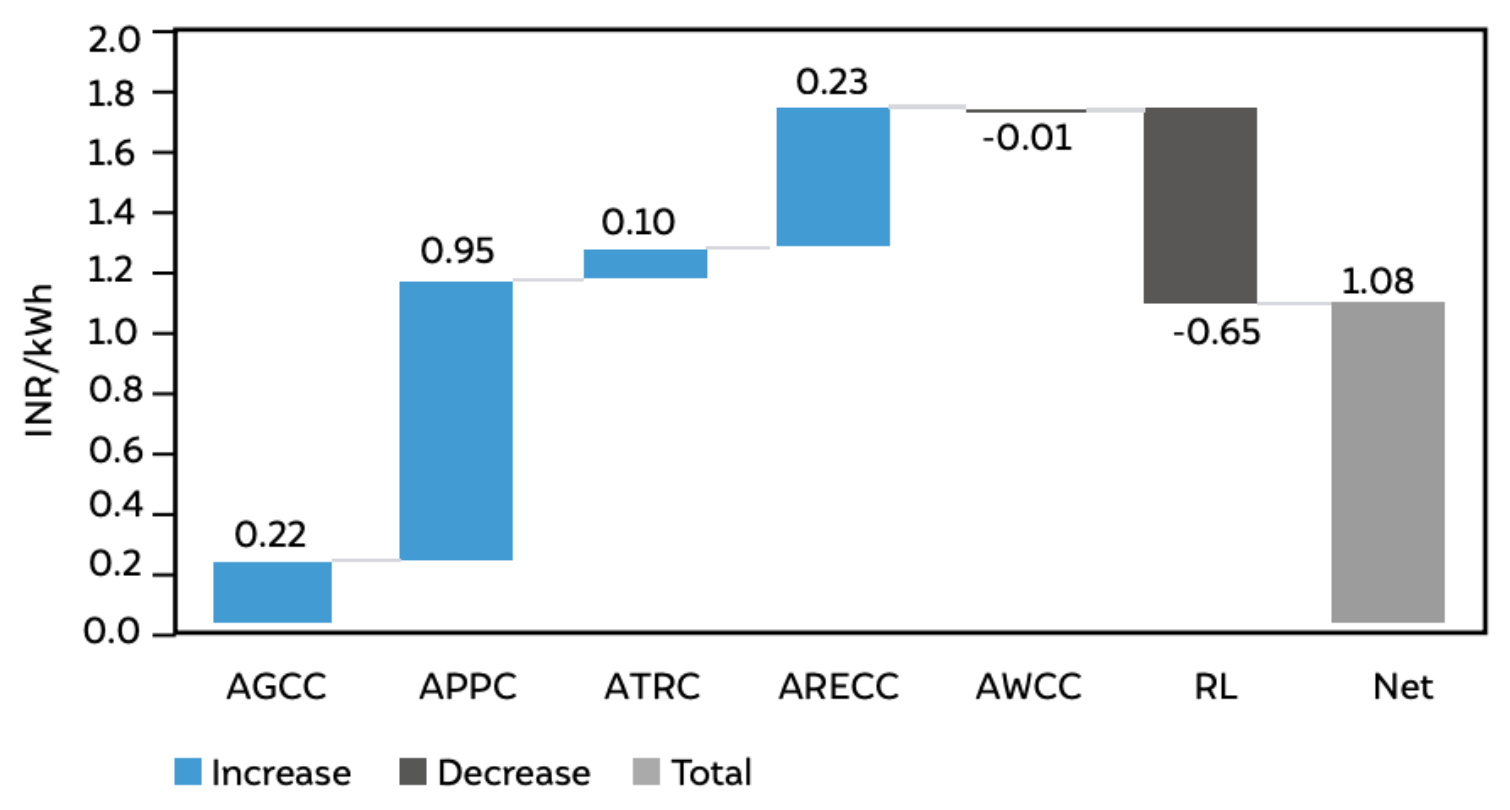

While applying the VGRS framework, we analysed the load profile of the discom and consumer. We found that the discom’s load varies significantly throughout the year. Besides variations during peak hours, the baseload also changes dramatically across seasons. The current practice of discoms dividing the year into two broad peak and off-peak periods to strategise their operations and use the microgrids is inefficient. Instead, using distinctive microgrid schedule and a battery dispatch for each season is more effective. Furthermore, there is a significant difference in the load profile of the discom and consumer. For BYPL, monsoon (July to September) is a peak period while winter (December to March) is the offpeak season. For the consumer, on the contrary, summer (April to June) is the peak season and demand tends to be softer during the monsoons. These differences make it challenging to schedule the dispatch of stored electricity from the battery such that it assists both stakeholders equitably.

To estimate the impact of these different demand curves, and the roles of PV and BESS, we developed four scenarios for the feasibility analysis. For the discom, these are PV only (Scenario 1/Sd1), PV-BESS (Scenario 2/Sd2), PV-BESS-Grid (Scenario 3/Sd3), and optimised PVBESS-Grid (Scenario 4/Sd4).

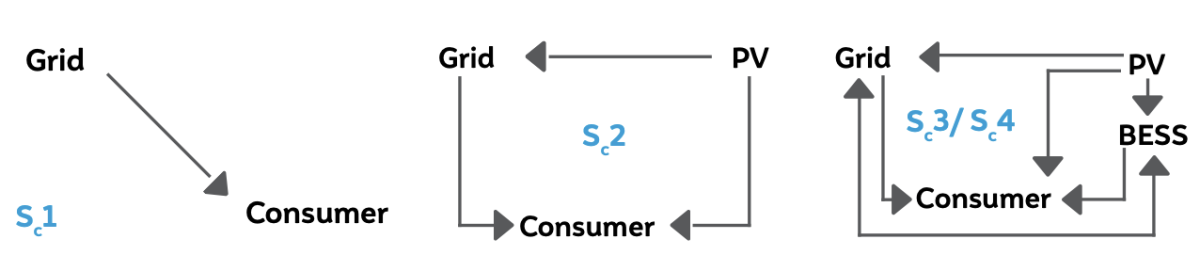

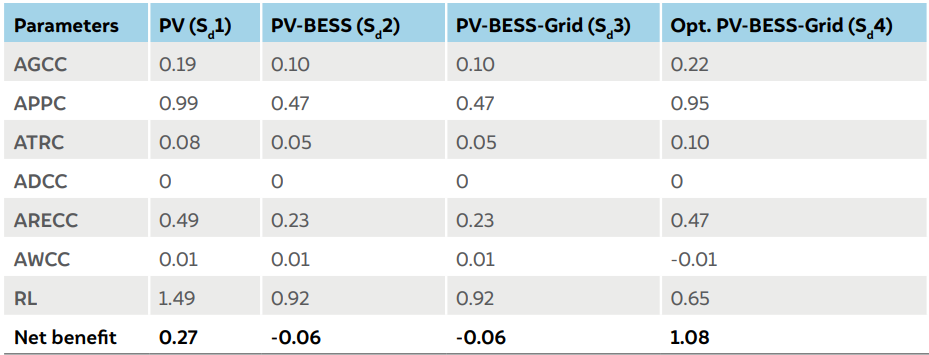

In these four scenarios, we calculated the impact PV and BESS have on discom revenues by considering different costs and benefits. Among the costs, we discussed revenue loss (RL) to discoms due to changes in the consumer’s reliance on the grid. As for the benefits, we looked at the savings from reduced procurement of generation and transmission capacity (avoided generation capacity cost/AGCC and avoided transmission charges/ATRC, respectively), power (avoided power purchase cost/APPC), and renewable energy certificates (avoided renewable energy certificate cost/ARECC), along with deferred upgradation of the distribution network (avoided distribution capacity cost/ADCC). Lastly, we looked at the net impact of these expenses and earnings on discoms, as reflected in their working capital requirement (avoided working capital requirement/AWCC). Table ES1 summarises the results from the four scenarios in the form of generation-normalised net present value for 25 years (INR/kWh).

Table ES1 BYPL makes the highest profit in scenario 4 (Sd4)

Source: Authors’ analysis

Among the different benefits, the savings from APPC represent 54 per cent of the cumulative benefits to the discom. This is driven by the increased export of solar electricity to the grid, which helps discom minimise their power procurement costs both from short-term purchases and scheduled procurements under long-term PPAs (power purchase agreements). Overall, in Sd1 (PV), BYPL makes a profit of INR 0.27 for each unit of solar electricity generated in its service area from the analysed 7 kW capacity. In contrast, in Sd2 (PV-BESS) and Sd3 (PV-BESSGrid), BYPL loses INR 0.06, for each unit of solar electricity generated based on the analysed capacity. Finally, Sd4 (Opt. PV-BESS-Grid) yields the maximum profit of INR 1.08, indicating that optimising battery usage (charge–discharge intervals) according to the seasonal load experienced by the discom can enhance the benefits these systems offer discoms.

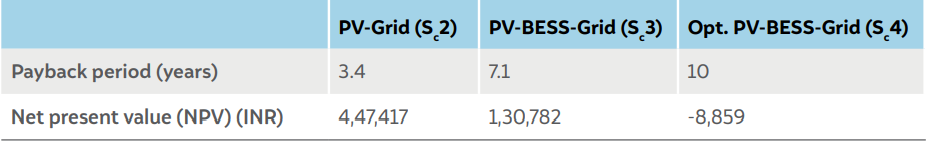

A similar procedure was adopted for the consumer. Here, the base scenario of the grid (Sc1) is compared to PV only (Sc2), PV-BESS-Grid (Sc3), and optimised PV-BESS-Grid (Sc4). The motivation was to estimate the impact of prioritising the operations of a microgrid for discoms over consumer finances. The economic viability of installing RTS and BESS for consumers was determined by the payback period and net present value (NPV). These parameters are essential to understand if the system will be economically lucrative or incur losses. Table ES2 shows various financial metrics over the lifetimes of microgrids. For the PV system alone (Sc 2), the consumer can recover the installation cost within three years, and the NPV is INR 4,47,417. Here, the consumer saves an average of 69 per cent on their monthly electricity bills. In the case of PV-BESS-Grid (Sc3), the payback period increases to seven years. This is driven by reduced savings on the electricity bill (59 per cent) and the capital and replacement cost of the battery. As expected, the NPV is reduced to INR 1,30,782. The modelled optimised Opt. PV-BESS-Grid scenario (Sc4) has the longest payback period of ten years and an NPV of INR -8,859. The average electricity bill savings are reduced to 37 per cent. These results indicate that the preferential utilisation of supply from microgrids for discoms leads to an increased financial burden for consumers.

Table ES2 Payback period for the consumer is shortest in scenario 2 (Sc2)

Source: Authors’ analysis

This case study highlights some vital recommendations for future system design and deployment. First, we need regulatory provisions to support dispatch by the consumers from behind-the-meter storage to the grid. Such provisions would allow discoms to utilise the exported electricity to reduce power procurement, manage peak demand, and minimise transmission and distribution losses. At the same time, it is necessary to optimise the permissible export of electricity to the grid. Besides prioritising consumers for greater favourable gain, excess export to the grid might be challenging for discoms to manage. Therefore, to sustain equitable benefits for consumers and discoms alike, regulations should focus on restricting the permissible export of electricity to the grid to promote selfconsumption by consumers, while ensuring access to electricity for discoms within the manageable technical limits. Next, to encourage uptake by consumers, we need differential time-of-day tariffs for battery export for all consumer categories. Such tariffs can be designed to incentivise consumers to export electricity to the grid during peak hours or to charge battery from the grid during off-peak hours. Lastly, to ease the financial burden imposed by high system costs on consumers, discoms should implement new business models based on cost-sharing and leasing. Such support policies and innovative market frameworks are a prerequisite for the proliferation of urban microgrids on a large scale.

Urban microgrids have applications in managing intermittent solar generation and in reducing solar export to the grid with increased self-consumption. These applications lead to many indirect benefits to discoms, including reduced peak demand, lower transmission and distribution losses, distribution network upgrade deferral, etc. Greater transparency regarding these benefits, from discom and consumer perspectives, is essential to devise innovative policy, regulatory, and market interventions to support the higher uptake of microgrids. The following section outlines some of the key findings from the BYPL case study. A detailed assessment of the economic viability of installed microgrids provided the following insights:

The discom peak demand in urban centres, with the increased penetration of air conditioners and electric vehicles, is likely to rise sharply in the coming years. This would also shift demand patterns from having uniform peak and off-peak periods to featuring intermittent peak and off-peak hours. As discussed, urban microgrids with dispatchable storage would provide greater benefits to discoms and contribute to smoothing the demand curve. The proliferation of urban microgrids, however, is contingent on various support policies and innovative market frameworks:

Enabling a Circular Economy in India’s Solar Industry

Community Solar for Advancing Power Sector Reforms and the Net-Zero Goals

Mapping India’s Residential Rooftop Solar PotentialA bottom-up assessment using primary data

Promoting the Use of LPG for Household Cooking in Developing Countries