Suggested Citation: Soman, Abhinav, Karthik Ganesan, and Harsimran Kaur. 2019. India’s Electric Vehicle Transition: Impact on Auto Industry and Building the EV Ecosystem. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

This report, supported by Shakti Sustainable Energy Foundation, explores various aspects of India’s transition to electric mobility. It examines the impact it would have on the automotive value chain, particularly on the automotive components industry and the jobs in this sector. The report quantifies the impacts and proposes strategies to ensure a transition trajectory that can mitigate any adverse fallout. Further, it maps the current e-mobility ecosystem in India and compiles the various policy, finance, and supply chain challenges that the various stakeholders face.

The automotive industry in India is facing headwinds – from a general economic downturn to the need to improve emissions performance and the impending shift to electrification. Charting the future course of the auto industry, especially with regard to electrification, will require an in-depth understanding of the opportunities and impacts that can be expected. In this study, we have attempted to assess these by comparing a scenario with 30 per cent electric car (EV) sales in 2030 against a business-as-usual (BAU) scenario with limited EV penetration.

Beyond 2030, several countries with a significant export share of car and car auto components today are targeting 100 per cent EV sales. This may present a lost opportunity for the Indian auto industry if they are unable to capture the fast-growing global EV market due to limited capability and expertise in EV manufacturing.

We find that, despite the fewer components needed for producing an electric car, the localisation of electric powertrain and battery pack assembly can result in a 5.7 per cent higher output value addition for the auto industry in a 30 per cent electric car sales scenario, when compared to value addition in a BAU scenario in 2030. However, with limited indigenisation of powertrain and battery pack assembly, there will be an 8 per cent lower value addition from an EV transition in 2030.

Around 20 to 25 per cent fewer additional car manufacturing jobs will be created in a 30 per cent electric car sales scenario, but there will be no job losses as a result of the transition. However, it is critical to ensure that a trained workforce is made available for the new EV manufacturing jobs that will be created, which would require new and different skill sets.

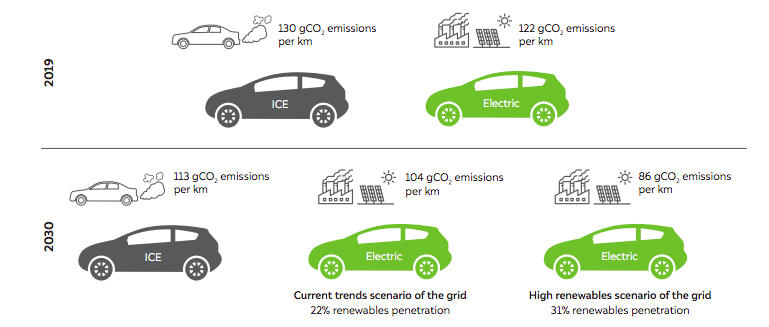

Electric car use can have positive impacts from macroeconomic and environmental standpoints. Specifi cally, the import burden per internal combustion engine (ICE) car will be 4.1 times higher for private cars and 5.7 times higher for commercial use cars when compared to electric cars over their lifetimes, when comparing oil and battery cell imports in 2030. CO2 emissions per electric car will be, in addition, 8 to 24 per cent lower than that of an equivalent ICE car over its lifetime in India.

Further, based on consultations with 28 stakeholders from the EV ecosystem in India, we have identified supply chain, policy, and financing barriers that are impeding the growth of EVs in India today. Overall, while there is a strong case for transitioning to EVs, as identified in this study, a policy package will be needed to address the existing barriers and develop a thriving EV ecosystem in India.

Source: Harsimran Kaur/CEEW

The automotive industry has been an important contributor to macroeconomic growth and employment in India since its inception. The industry is undergoing a transition on many fronts, with the introduction of stringent emissions norms, automation, and policies in favour of electrifying transport. We looked at how a transition to electric vehicles will impact the auto industry to determine arguments for and against electrification.

At the outset, while there is room for growth in ICE car sales even with 30 per cent electric car sales in 2030, investment decisions regarding whether to expand ICE car manufacturing capacity will require information on projected EV sales.

Countries across the world are undertaking EV transitions, and given India’s ambition to become a global hub for auto manufacturing, building an EV ecosystem in India is of strategic importance. The burgeoning global EV market is a potential opportunity that the Indian automotive industry could exploit.

With a concerted effort to indigenise both electric car powertrain and battery pack assembly, the Indian automotive industry can produce a 5.7 per cent higher value add in a 30 per cent electric car sales scenario than in a business-as-usual (BAU) scenario with limited electric car penetration. On the other hand, with limited indigenisation of powertrain and battery pack assembly, there will be an 8 per cent lower value addition from car manufacturing in 2030 as compared to BAU. While we have not considered cell manufacturing in India, it is an additional avenue for creating further value addition.

Given the lower job intensity associated with manufacturing the powertrain of an electric car, around 20–25 per cent fewer jobs will be supported in a 30 per cent electric car scenario as compared to BAU depending on the level of indigenisation. This does not translate to ‘job loss’ due to an EV transition as is often claimed and is true of countries where car sales have plateaued. Instead, for India, this means that fewer additional jobs will be created in car manufacturing in the future in case of 30 per cent electric car penetration in new sales. The new EV jobs will, however, require a trained workforce which does not exist in India today, and therefore reskilling as well as vocational training will be critical to achieving the EV sales target.

Importing battery cells for electric cars will be cheaper than importing the oil needed for ICE cars in 2030. The import burden per ICE car is 4.1 times higher for private vehicles and 5.7 times higher for commercial vehicles compared to the import burden of an electric car over its lifetime, considering oil and cell imports, respectively. The economic benefits of reduced spending of forex reserves on oil imports make a strong case for an EV transition. We also find that in addition to reducing local air pollution, CO2 emissions per electric car will be 8 to 24 per cent lower in 2030 (depending on renewable energy penetration in the grid), highlighting the environmental case for an EV transition in India.

While compelling reasons for electrifying transport abound, the EV ecosystem in India is still in its infancy. Various existing and upcoming stakeholders today face supply chain, policy, and financing barriers as documented in this report. Market entry for potential EV manufacturers is challenging on account of these factors, which explains the lacklustre performance against the existing NEMMP target for 2020. Additional policy interventions that improve the attractiveness of electric cars vis-a-vis ICE cars, targeting both supply and demand, are urgently needed if EV targets are to be pursued for 2030.

A transition to e-mobility will upend the automotive industry and will have commensurate impacts on other sectors of the economy. A thorough assessment of the net impact of such a transition on the economy, and the extent to which it addresses externalities, should shape India’s decisions to develop this emerging industry. Meanwhile, it is also important to be cognizant of the efforts required to develop an EV ecosystem in India, and the timelines involved in building competence indigenously in manufacturing so as to reap the maximum benefi ts from this transition. While the EV transition seems inevitable and is gaining momentum in India, a concrete pathway for the future of e-mobility, that expounds on priorities and incorporates Indian realities, is the need of the hour.

The Road Ahead for Private Electric Buses in India

A Feasibility Study of Electric Bicycles

How Does Intermediate Public Transport (IPT) System Operate in Lucknow?

Decarbonising Shipping Vessels in Indian Waterways Through Clean Fuel