Suggested citation: Ghosh, Arunabha, and Sanjana Chhabra. 2021. Speed and Scale for Disruptive Climate Technologies: Case for a Global Green Hydrogen Alliance. A GCF-CEEW Report. Stockholm: Global Challenges Foundation.

This study gives an overview of the current status of green hydrogen globally and how it can be a game changer for heavy industries, such as steel, ammonia and petrochemicals, and transport. It proposes a Global Green Hydrogen Alliance to meet vital international clean energy needs. The study suggests that the alliance can be designed as a multi-country, multi-institutional network to assess, develop and design affordable green hydrogen technologies.

While many countries have announced national and regional hydrogen programmes, green hydrogen technology is still far from commercialisation at scale. Three trends — expected shifts in sectoral uses, geographical spread to emerging economies, and the need for low-carbon production — will serve as the foundations of a new wave of hydrogen production and consumption in the coming decades.

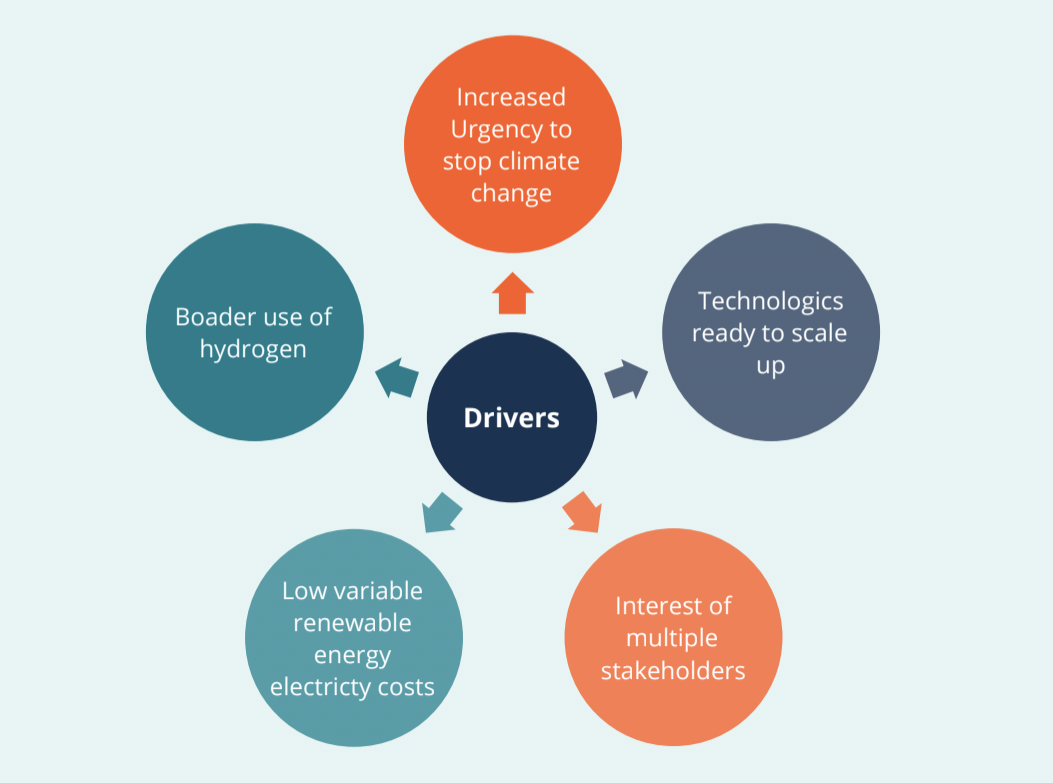

Drivers of green hydrogen

Source: CEEW Research and Analysis

Many major emitters have recognised that without significant industrial decarbonisation, pronouncements of net-zero would have little certainty. How would global industrial emissions be reduced at the pace needed for advanced economies and without deindustrialising fast-growing emerging economies? Green hydrogen could be a game-changer for heavy industries, such as steel, ammonia and petrochemicals, in addition to transport. Many countries have announced national and regional programmes but green hydrogen technology is still far from commercialisation at scale.

Three trends — expected shifts in sectoral uses, geographical spread to emerging economies, and the need for low-carbon production — will serve as the foundations of a new wave of hydrogen production and consumption in the coming decades. These shifts must unfold concurrently.

At least 32 countries plus the European Union have announced or are developing national-level policies and strategies for hydrogen. At least 24 countries and regions have targets and pilots for green hydrogen.

But the scale of transformation has not been fully internalised. Under IEA’s netzero scenario, low-carbon hydrogen use would have to be 19 times greater in 2030 compared to even its sustainable development scenario. The world needs more collaborative action.

There are more than a dozen bilateral partnerships and at least 10 multi-country or multi-firm platforms focused on hydrogen. But they seldom involve developing countries, are not oriented towards joint technology development, and do not focus on deploying technologies in countries that will have the greatest demand for cleaner fuels for industrial development.

Three challenges dominate. First, path dependency in national programmes could lead to sub-optimal outcomes related to technology choices (continued reliance on fossil fuels for hydrogen production), end uses (lesser focus on abating industrial emissions) and differential standards (for storage, transportation and safety).

Secondly, there is a gap between the geographical distribution of green hydrogen potential and the primary destination of investment and projects. Many countries in the tropics have optimal renewable resources and other low-carbon resources for producing hydrogen. But the bulk of the hydrogen programmes are concentrated in developed countries. Of the 33 countries and regions analysed, only seven are in Asia, two of which are developed countries and three are major oil and gas producers. Nearly all of the bilateral partnerships are among developed countries. Multi-party partnerships have primarily been promoted to support national programmes of the sponsoring country, rather than as genuine collaborative efforts.

The biggest obstacle is the absence of leadership. If green hydrogen has the potential to be a foundational fuel for industrial and transport decarbonisation, its development and deployment must be treated as a global public good. There is a need to avoid mercantilist instincts wherein technology development is restricted to a few countries, while trade dependence increases for a clean fuel.

A Global Green Hydrogen Alliance should be designed as a multi-country, multi-institutional network to assess, develop and design affordable green hydrogen technologies that can be deployed at scale, in both advanced economies as well as in developing countries. It would follow a six-step approach.

Step 1: Global inventory of hydrogen programmes and activities to increase transparency and help connect technology developers and firms across borders, creating conditions for collaboration.

Step 2: Periodic technology assessments (biennially) to help members be up-todate about what gaps remain and about new opportunities for joint research.

Step 3: Bilateral/plurilateral partnerships, with the rule being that any initiative would need sponsors from at least two countries to promote collaboration and reduce costs.

Step 4: Pooled funds for enhanced joint R&D, with members allowed to contribute in cash or offer their human resources and laboratory and industry facilities in kind. A portion of this pooled fund could be set aside as a corpus to underwrite R&D projects via partial risk guarantees.

Step 5: Rules of intellectual property ownership and licensing, wherein participating institutions retain their original IP while any new technology developed by a work programme consortium is jointly owned.

Step 6: Alliance-wide standard-setting and inspections for safe storage and transportation via technical supervisory committees having the mandate to set standards and protocols, build capacity in developing countries, and undertake periodic inspections.

The Alliance’s institutional design should prioritise scale, speed and risk. None of the six steps requires a large, bureaucratic secretariat. The Alliance could be designed on a networked governance model, with a governing council overseeing progress made by individual work programmes. Under the Alliance, pilot programmes could up and running in developing countries by 2025. Given pressing concerns about post-pandemic economic recovery, it is easier to see the value of pooling resources through a networked but global platform.

Finally, the Green Hydrogen Alliance must follow a risk-risk approach. These include failures in technological development or in end-use applications, secondorder risks associated with the adverse impacts of faulty storage or transportation of green hydrogen, and tertiary risks involving trade or intellectual property disputes. Set against these risks should be the assessment of the failure to combat climate change by not deploying technologies for industrial decarbonisation rapidly and at scale.

The Global Green Hydrogen Alliance, by building on the existing initiatives and correcting for their governance failures, can be tactically and operationally more efficient, but it would be most critical as a governance innovation at a strategic level.

This paper exposes the dangers of being too sanguine about climate-related announcements without requisite resources, effort or partnership. The first is the belief that merely declaring aggressive targets for decarbonisation is sufficient to deliver results. The pathways to industrial and transport decarbonisation are extremely difficult and need serious attention on the technological front, especially the production of green hydrogen from renewable energy resources. The second danger is that, even if the need to develop disruptive technologies is recognised, there is premature celebration of hydrogen programmes and platforms that do not address underlying challenges. Deeper examination reveals that much of the activity is concentrated in developed countries in Europe and North America. Despite being a critical source of future demand, Asian countries are barely involved in the development, demonstration or deployment of green hydrogen technologies.

The Global Green Hydrogen Alliance would be designed to fill these gaps, rather than substitute for existing platforms. It is proposed as an initiative that is more transparent, genuinely inclusive, capable of pooling resources from many countries, and developing technologies that can be shared and deployed at scale. The failure of global governance in climate technologies is not the absence of initiatives, but the low ambitions and lack of inclusion of many extant offerings. The alliance offers a rethink and reimagination of how climate-friendly technologies can be developed at scale and with speed, while paying attention to the underlying risks. If successful with green hydrogen, such models of technological collaboration could also be used for other disruptive technologies, from batteries to greenhouse gas removal. Many climate technology platforms in the past have encouraged discussions but few have jointly invested in R&D and even fewer have shown how pilots and large-scale commercialisation can be the vision for such initiatives. The limitations in concretely and effectively delivering global public goods starts with the limitations in our imaginations, and, relatedly, in our ability to construct suitable, powerful and collaborative frameworks/ capacities at the required planetary scale.

Assessing Effectiveness of India’s Industrial Emission Monitoring Systems

Evaluating Net-zero for the Indian Cement Industry

Evaluating Net-zero for the Indian Steel Industry

Accelerating the Implementation of India's National Green Hydrogen Mission

Best Practices in CEM (Continuous Emission Monitoring)