Suggested Citation: Agarwal, Nandini, Apoorve Khandelwal and Aradhna Wal. 2023. How to Design Scalable and Sustainable Programmes: Framework for India’s Sustainable Agriculture Initiatives. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

Click to read more about each case study

This report presents a scalability framework, a non-prescriptive tool for designing, implementing, and evaluating scalable programs for sustainable agriculture. The framework provides a set of outcomes that, when fulfilled, help a project achieve scale. These outcomes are communicated in the form of key success factors for scalability. The key factors are useful for a range of stakeholders such as NGOs, government departments, corporates, development financiers, and community-based organizations, among others.

The agrarian complexities India faces are large-scale and systemic, intertwined with socio-economic and environmental issues. Challenges of high input costs, deteriorating soil health, continued debt cycles, inequitable market access, and lack of financial security, specifically affecting small and medium farmers, can be overcome through high-impact and scalable solutions in a sustainable manner. In this context, sustainable growth and scalable impact were part of the Indian government’s agenda for its G20 presidency in 2023, with agriculture being one of the key focus areas.

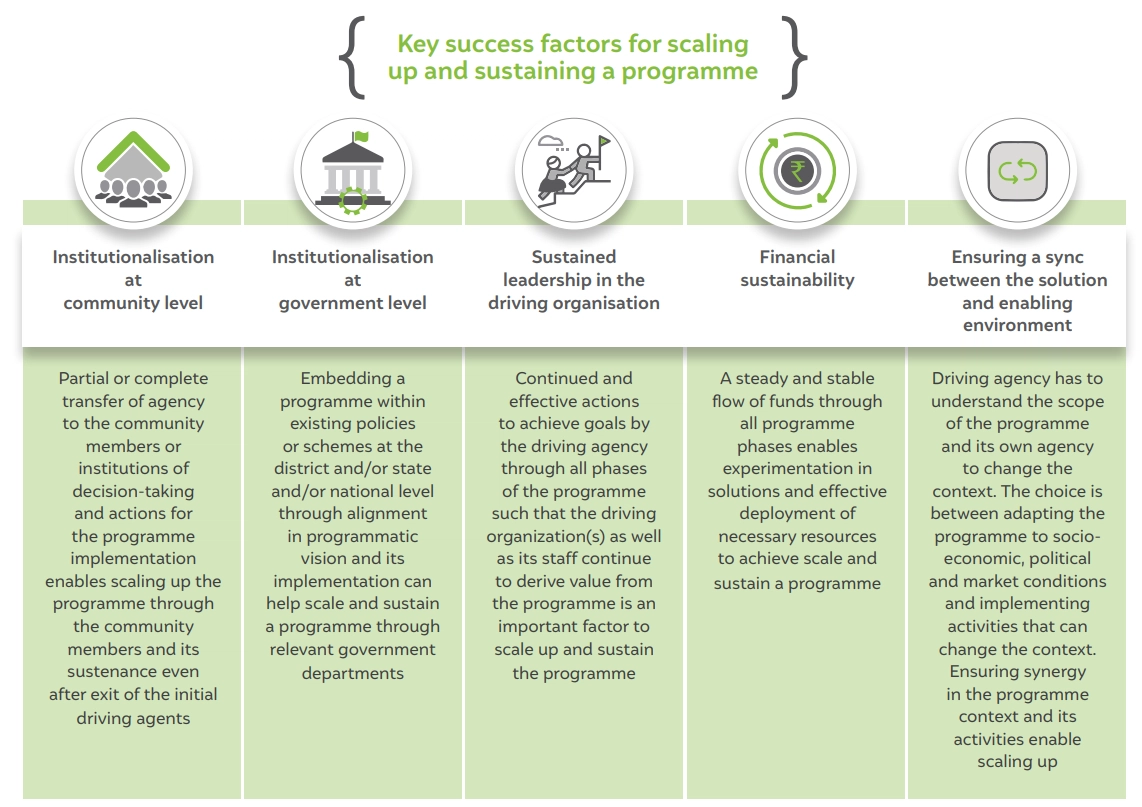

There are five key success factors that enable scaling up a program. These include:

It’s been decades since the Green Revolution, and India’s agricultural systems are facing a crisis resulting from high input costs, deteriorating soil health, continued debt cycles, inequitable market access, and lack of financial security, specifically affecting the small and medium farmers (Dutta 2012; Reddy and Mishra 2010). The crisis is compounded by extreme climate events—droughts, floods, untimely rains, and desert locusts—which have harshly impacted farmers across the country (Gupta et al. 2021). The agrarian crisis has become acute because sustainable agricultural practices and systems (SAPSs) are not widely practiced. Only five SAPSs—crop rotation, agroforestry, rainwater harvesting, mulching, and precision—have scaled up beyond five per cent of the net sown area (ibid). As the challenges we face are large-scale and systemic, intertwined with socio-economic and environmental issues, high-impact and scalable1 solutions are needed to counter them. A viable solution comes in the form of SAPSs, which are capable of achieving multiple outcomes:

Sustainable growth and scalable impact are part of the Indian government’s agenda for its G20 presidency in 2023, with agriculture being one of key focus areas. Mission LiFE, a mass movement for individual and community-led scalable actions for sustainable production and consumption, was already launched in the country in 2022. At the Government of India’s urging, the United Nations declared 2023 as the International Year of Millets (IYM). India is also the chair of IYM’s Steering Committee, with a mandate to scale up millet production among UN member nations.

In the light of such fierce ambitions and timely calls for action, practitioners need to design scalable programmes to make a sizeable impact and bring the required systemic shifts. Our report answers the question, “What are the factors that ensure the scalability of a programme?” Many innovative solutions and projects operate in India. Only those with a high degree of an understanding of and access to social and human capital, financial resources, and government support scale up as we have explained in this report.

Existing scalability literature rarely draws from the Indian experience and hence not useful to practitioners or programme implementers. Therefore, actors such as non-governmental organisations (NGOs), government departments, corporates, development financiers, and community-based organisations will benefit from this scalability framework that extracts learning from successfully scaled up programmes for sustainable agriculture in India. This report is aimed at the following stakeholders to help them design, implement, and evaluate scalable programmes:

The scalability framework provides a set of outcomes which, when fulfilled, helps a project achieve scale. These outcomes are communicated in the form of key success factors for scalability. These key factors should be kept in mind while designing and implementing scalable programmes. Any organisation (NGOs, CSOs, corporate, government department, investor) that wishes to drive or evaluate their project’s ability to scale up and sustain can use this framework.

Figure ES1 Five key success factors that enable scaling up of a programme

Source: Authors’ compilation

Institutionalisation at the community level is a partial or complete transfer of agency of taking decisions and actions for the programme to community members or community-level organisations. The community starts expanding the ambit and the vision of the programme, which was done earlier by the programme initiator. This was exemplified in the Tasar Silk Value Chain case study, where the nongovernmental organisation (NGO) Professional Assistance for Development Action (PRADAN) moved out of its active interventional role and community members took over the strategic thinking for and engagement with the tasar silk value chain.

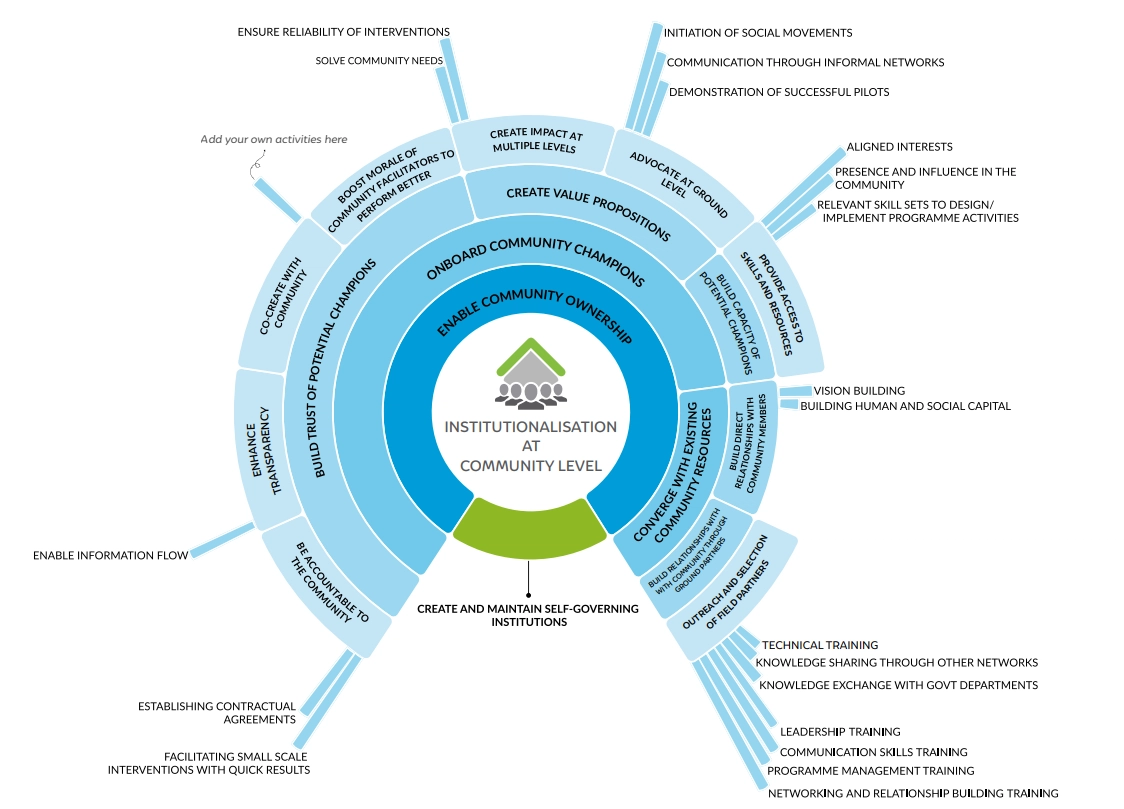

Figure ES2 Success factors that drive institutionalisation at community level

Each arc represents a key success factor (here, institutionalisation at community level is enabled by its own set of enabling factors as you move outwards from the center).

The spokes are jump-off points. Put simply, they are a set of activities, pathways, mechanisms, or tips for the implementing organisation to drive the related success factor. Can you think of additional activities from your experience?

Source: Authors’ analysis

If a programme fulfils the community’s needs, aligns with their interests, and deploys resources to skill and capacitate the community members, it can deepen its reach within the community to establish their ownership and agency. Thus, one of the ways to ensure institutionalisation at the community level is by enabling community ownership. In addition, institutionalisation at the community level can also be achieved by self-governing institutions.

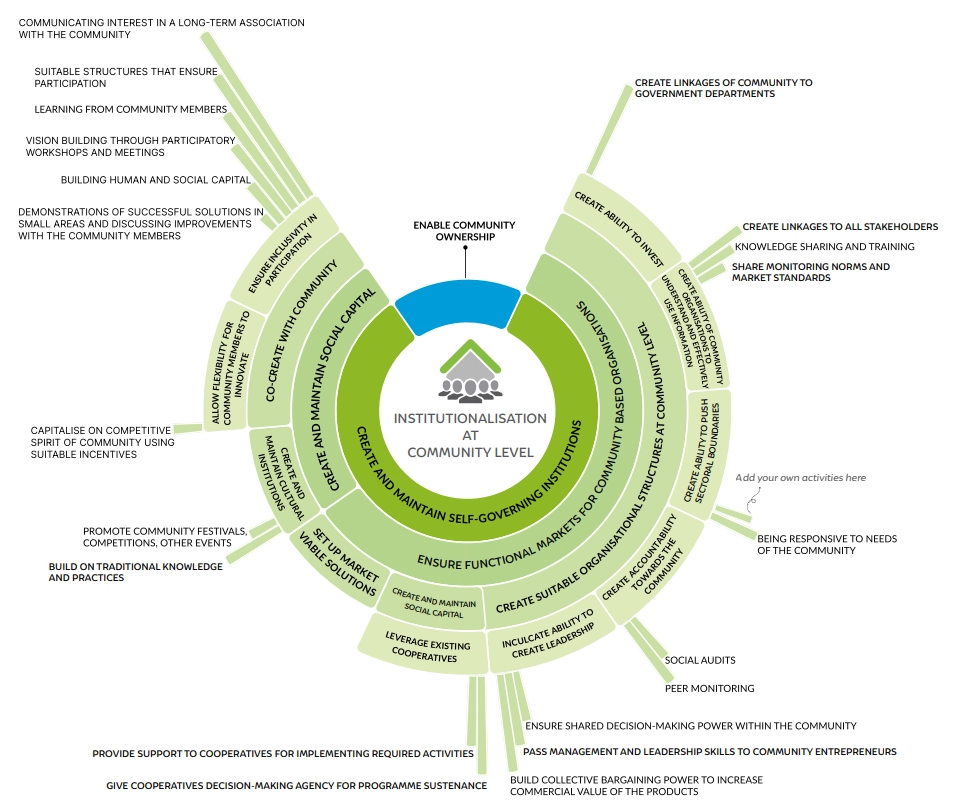

Source: Authors’ analysis

Embedding a programme within the existing policies, schemes, or department missions through a formal alignment of its vision and mission with the state and/or national government can create institutionalisation of the programme within the government. Through case analysis, we understand that such integration of a programme with government departments at the national or subnational levels can propel a programme to scale up at a high velocity.

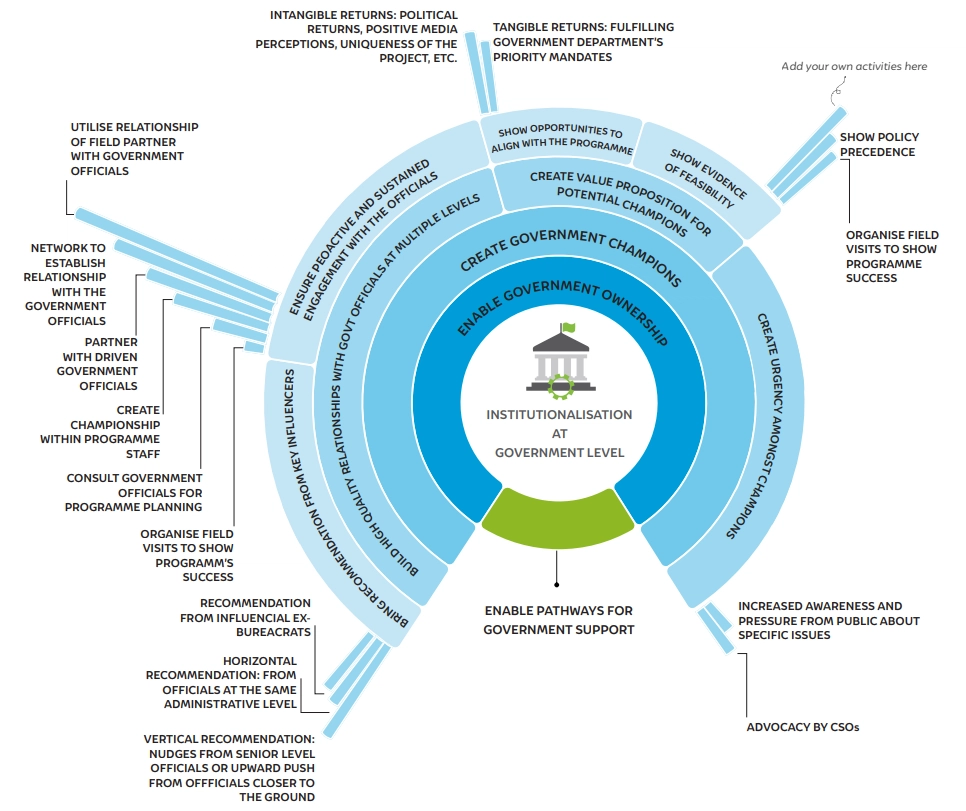

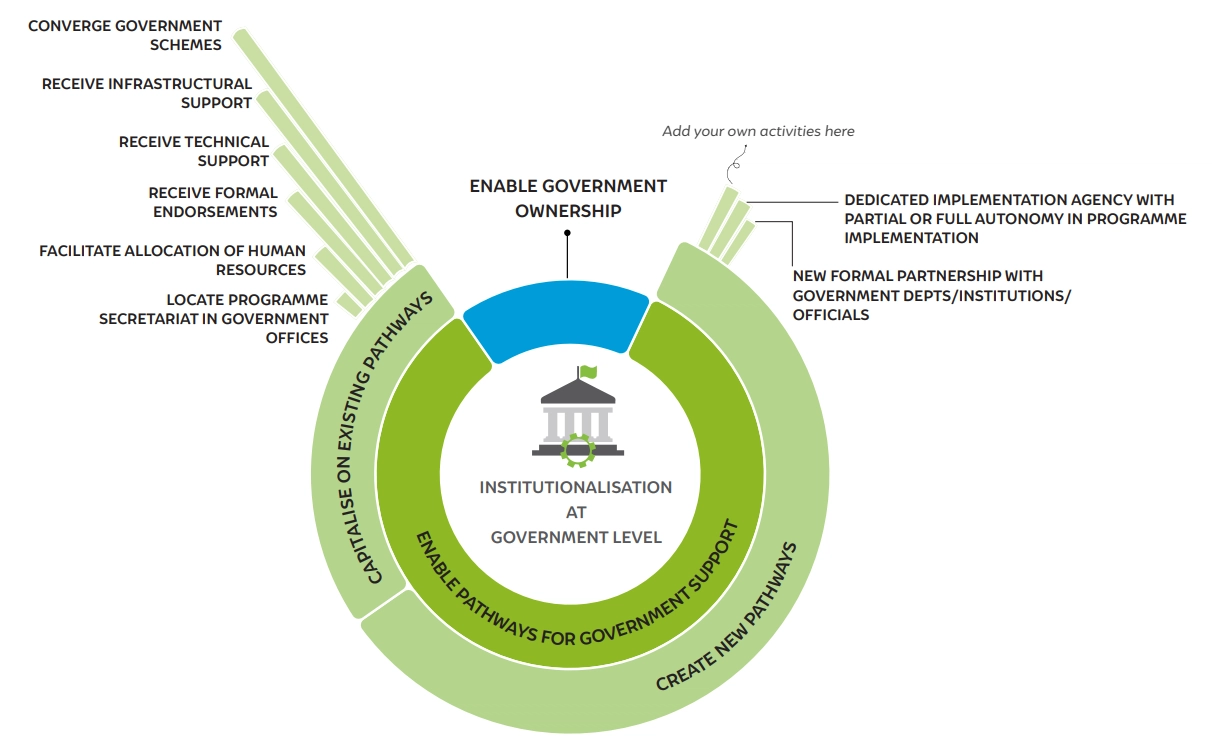

Figure ES3 Success factors that drive institutionalisation at government level

Each arc represents a key success factor (here, institutionalisation at government level is enabled by its own set of enabling factors as you move outwards from the center).

The spokes are jump-off points. Put simply, they are a set of activities, pathways, mechanisms, or tips for the implementing organisation to drive the related success factor. Can you think of additional activities from your experience?

Source: Authors’ analysis

This is evident in the trajectory of the Odisha Millet Mission (OMM) case study, where the state government launched an official mission on millets to promote their production and consumption by creating strong market linkages for farmers. While the existing Revitalising Rainfed Agriculture Network (RRAN)-led programme was already successful at district levels, its institutionalisation at the government level facilitated the scaling up of the OMM programme. Institutionalisation at the government level can be facilitated by government ownership and by enabling pathways for the government to support the programme.

Source: Authors’ analysis

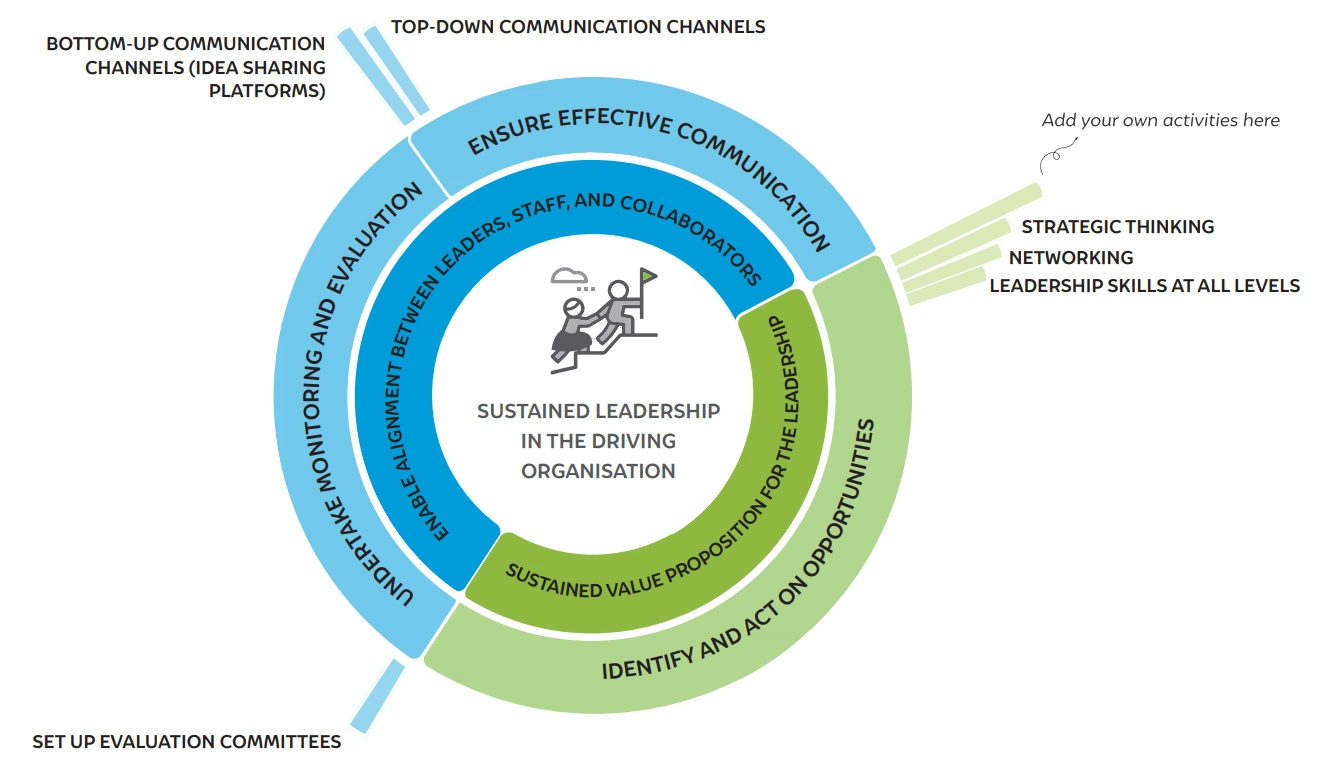

Sustained leadership refers to the continued and effective actions towards programmatic goals by the programme driver. This leadership in the driving organisation should back the programme throughout its trajectory, even if the programme were to move from one driving organisation to the other. We found that the management at Andhra Pradesh Community-Managed Natural Farming (APCNF) instilled such leadership among the programme staff, from ground level up to higher executive levels, through constant communication and alignment on programme objectives and vision. Sustained leadership in the driving organisation can be ensured when the driving organisation derives constant value from the programme, and when there is alignment among the leaders, staff, and collaborators of the programme on the vision, mission, and execution.

Figure ES4 Success factors that drive sustained leadership in the driving organisation

Each arc represents a key success factor (here, sustained leadership in the driving organisation is enabled by its own set of enabling factors as you move outwards from the center).

The spokes are jump-off points. Put simply, they are a set of activities, pathways, mechanisms, or tips for the implementing organisation to drive the related success factor. Can you think of additional activities from your experience?

Source: Authors’ analysis

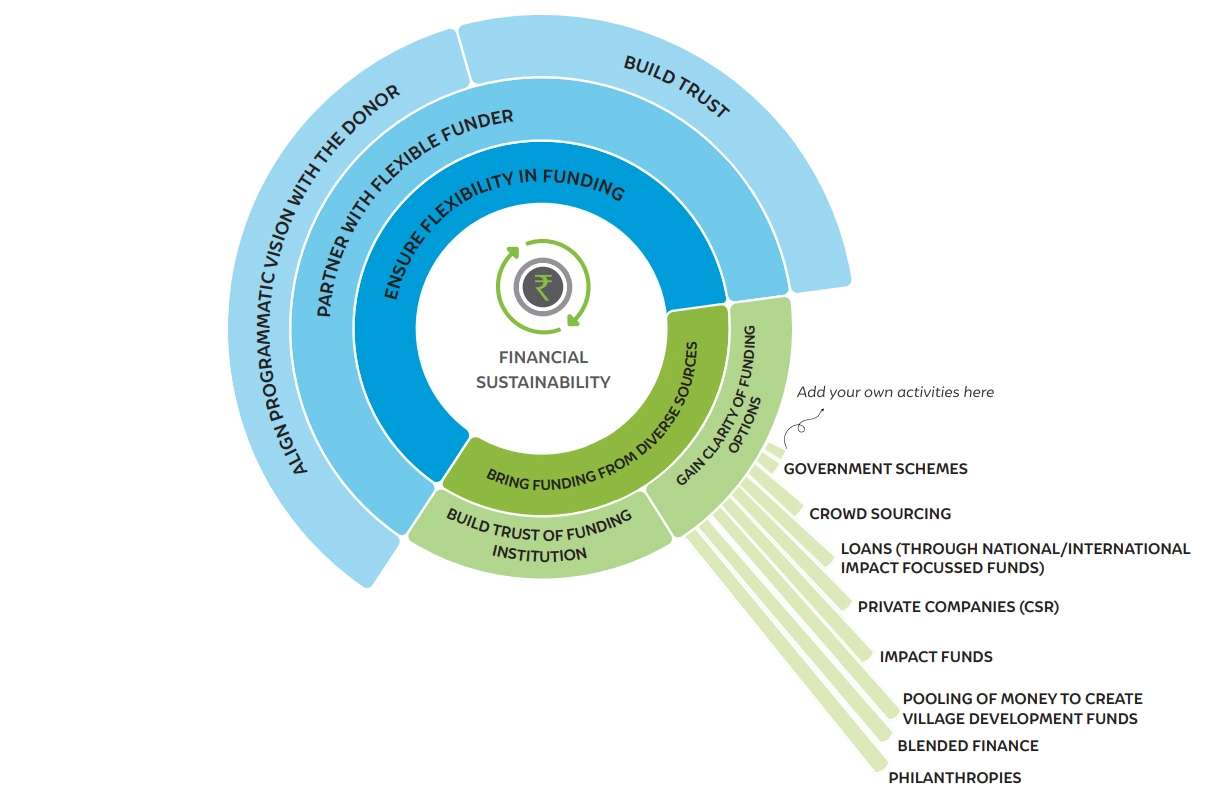

Financial sustainability is imperative for scaling up a programme. Irrespective of whether the programme is in its pilot stage or has reached the national level, the driving organisations or institutions have to ensure a steady and stable flow of funds for further scaling up and sustenance of the programme. Financial sustainability can be enabled by ensuring diversity and flexibility in funding sources. There are several options to access a diverse portfolio of funds, such as government schemes, corporate social responsibility (CSR) funds from private companies, development funds, philanthropies, and impact funds. It is important for the programme driver to have clarity on what kind of funds their programme requires. For example, during the tasar value chain pilot stage, PRADAN was conscious of their need for flexibility to deploy funds to conduct experiments for finding the right technical solutions. Thus, they looked for funders who were aligned with their approach and long-term programme goals. In all instances, it is important for the driving organisation to build the funder’s trust.

Figure ES5 Success factors that drive financial sustainability

Each arc represents a key success factor (here, financial sustainability is enabled by its own set of enabling factors as you move outwards from the center).

The spokes are jump-off points. Put simply, they are a set of activities, pathways, mechanisms, or tips for the implementing organisation to drive the related success factor. Can you think of additional activities from your experience?

Source: Authors’ analysis

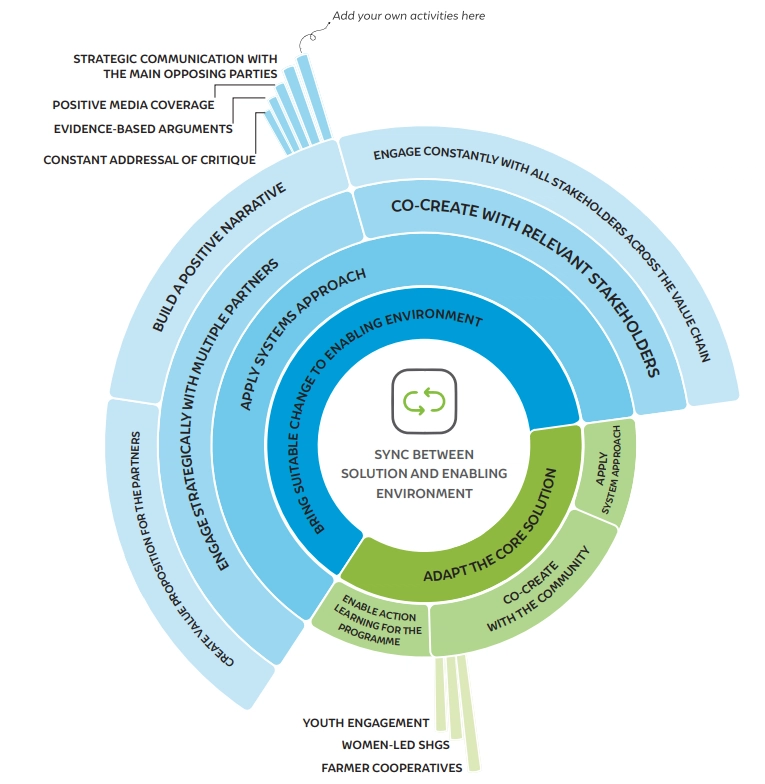

Each core solution of the programme is implemented in a given context. It operates within a political economy in the presence of certain social structures, physical infrastructure, natural resources, and financial resources. Some aspects of this enabling environment are beyond the influence of the driving organisation. For example, certain policy changes, the presence of external stakeholders, or technological innovations may affect the programme. On the other hand, the core solution refers to activities that the programme undertakes to solve the given challenges and achieve the programme objectives. These are the key programmatic solutions that the implementers have the influence to implement according to the context. For example, adopting a new technology for the sustenance of the programme, or partnering with stakeholders to increase market linkages for the programme. For all programmes, it is important to ensure a sync between solution and enabling environment to scale up.

Figure ES6 Success factors that ensure a sync between solution and enabling environment

Each arc represents a key success factor (here, a sync between solution and enabling environment is enabled by its own set of enabling factors as you move outwards from the center).

The spokes are jump-off points. Put simply, they are a set of activities, pathways, mechanisms, or tips for the implementing organisation to drive the related success factor. Can you think of additional activities from your experience?

Source: Authors’ analysis

It is important to understand the scope of this framework so as to most effectively engage with the theory:

The team shortlisted six cases from India based on select criteria such as programmes’ focus on vulnerable populations, diversity of the driving agencies (NGOs, governments, private companies), and agro-climatic zones in which they function (see the Research Approach section to read more on case study selection).

Our team used grounded theory to analyse the cases presented below. From each programme’s strategic decisions on what activities to undertake, and their successes, challenges, and failures, we extracted the reasons for how they scaled up and sustained. Through this method, we have generated the theory of scaling up solutions relevant to agriculture in India and presented it in the form of a scalability framework in this report. We triangulated our findings with experts working on the ground for programme implementation, in the finance sector and in the government sector. Our motivation is to enable the user to scale up solutions that drive sustainability in agriculture by applying this framework, which presents the DNA of scalable projects.

APCNF is a government-driven natural farming programme, implemented by the Rythu Sadhikara Samstha (RySS) in Andhra Pradesh. RySS, a body functioning under the aegis of the state agriculture department, implemented the APCNF in 13 districts, in 2015, by building on the precedents set by the Zero Budget Natural Farming (ZNBF) movement in the neighbouring states. As the programme scaled up from just over 40,000 farmers, in 2015, to 750,000 farmers, 2018 onwards, it established natural farming as a pathway for alleviating agricultural debt cycles, skilling farming communities, and creating community cadres for programme ownership by the community.

The NGO PRADAN established a long-running programme on tasar sericulture in pre-divided Bihar in 1988, which continued in the districts across Bihar and Jharkhand, eventually scaling up to seven states across India. Its objective was to learn from and improve on traditional sericulture practices of tribal communities, improve their livelihoods, and create strong units of leadership within the participating communities. To achieve these objectives, the programme trained and empowered tribal youth to take on entrepreneurial roles to support the tasar value chain. PRADAN won the cooperation of the Central Silk Board (CSB) and eventually the union Ministry of Rural Development (MoRD).

Revitalising Rainfed Agricultural Network (RRAN) piloted the OMM (known as the Malkangiri pilot) in 2012. It reintroduced millets in districts of Odisha as a hardy, drought-resistant crop better suited to the state’s climatic conditions and the needs of tribal farming communities. RRAN and their ground partners targeted interventions not only at farmers and farmer-related institutions but also roped in government’s tribal schools to be millet-based food consumers. The programme cemented support among the community, from the district, and eventually state government departments. The state government took over OMM in 2017 as its flagship programme for millet-based agriculture. From a pilot in four blocks of Malkangiri, in 2012, the programme has scaled up to 142 blocks, across all of the 19 districts in Odisha by 2022–23.

Tarun Bharat Sangh (TBS) initiated and scaled-up successful water resources revitalisation programmes in arid areas of Rajasthan, based on gram swaraj or self-rule for villages. In its initial years, the programme built rainwater harvesting structures, revived rivers and ensured equitable sharing of community resources. In its first three years, it helped communities build 24 rainwater harvesting structures, As the programme scaled up, the River Arvari Parliament of 142 villagers, nominated by their gram sabhas, was formed to protect the revived river Arvari from a government-sanctioned external fishing contractor and establish sustainable agricultural practices on the nearby land. TBS went on to initiate national and international water conservation forums and campaigns that even resulted in the government designating Ganga as the national river.

Engineer Sonam Wangchuk built the pilot ice stupa in the Union Territory of Ladakh in 2014 to alleviate water scarcity in the region. Wangchuk’s design improved on the older technology of artificial glaciers and leveraged the region’s historic practices of collective water management to encourage community ownership. The ice stupa is built as a single, freestanding tower made of ice that does not melt easily. It stores the water available in cold weather till the following spring, to be used for irrigation, ensuring the community’s access to water. The project started with a successful six-metre-tall prototype in one village and scaled up to 16 villages within four years.

In 2000, ITC launched a pilot to create direct links with farmers they procured agriculture and aquaculture products from. The pilot focused on forming an IT network across rural regions of 10 states by creating communication hubs called E-choupals, and community members were trained in entrepreneurial skills to operate these hubs. It gave community members easy internet access and information technology skills and created an electronic marketplace. The programme enabled them to connect directly with buyers and access important information on rates and market trends, gather knowledge on better agricultural practices, realise faster payments, get weather advisories, and avail crop insurance.

Readers interested in understanding how the programmes we analysed overcame certain barriers are invited to read the detailed case study chapters. They elaborate the activities the programmes undertook in each phase and explain their trajectory.

This scalability framework is a non-prescriptive tool for designing, implementing, and evaluating scalable programmes for sustainable agriculture. It is useful for a range of stakeholders such as NGOs, government departments, corporates, development financiers, and community-based organisations, among others. It offers them insights into the successes of previous programmes and aids in decision-making in diverse contexts and throughout the programme trajectories. We encourage users to apply the success factors as per their programmatic needs. You may find that some success factors would be more relevant to your context than others; for example, if the need of the programme is to engage with the community, then you may refer to the key factor ‘institutionalisation at the community level’. However, the more (and the more deeply) key factors are achieved, the higher the chances of scaling up.

This study has the potential to evolve in many ways—take a deeper look at the risks attached to the implementation of each success factor and how programmes can account for them; understand how success factors are interconnected with one another; further allocating weightage to key and sub-success factors to help users prioritise them according to their contexts.

Policy Study on Re-calibrating Institutions for Climate Action

Millet Mantra - The Culinary Centrepiece of India's G20 Presidency

Identifying Pathways for Scaling Up Climate-Smart Agriculture

Policy Study on Sustainable Agriculture