Suggested citation: Patnaik, Sasmita, Shaily Jha, and Tanvi Jain. 2021. Improving Women’s Productivity and Incomes Through Clean Energy in India. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water

The study discusses the barriers faced by women micro-entrepreneurs, who are using clean energy-powered livelihood technologies, in accessing finance and policy support. It highlights the potential opportunities for integrating women into the renewable energy ecosystem. It examines how businesses can be scaled up to ensure greater participation of women as entrepreneurs, value chain partners, employees and customers. The study details solutions and recommendations for a range of stakeholders (donors, policymakers, financiers, incubators and enterprises) who could help women scale up the use of renewable energy powered livelihood technologies in their businesses.

Barriers and opportunities for women-led micro-enterprises

Source: Authors' compilation

Loans and clean energy enterprises are the primary source of financing to use DRE-powered products

Investors and donors

Policymakers

Financial Institutions

Entrepreneurship Development Programmes

Clean Energy Enterprises

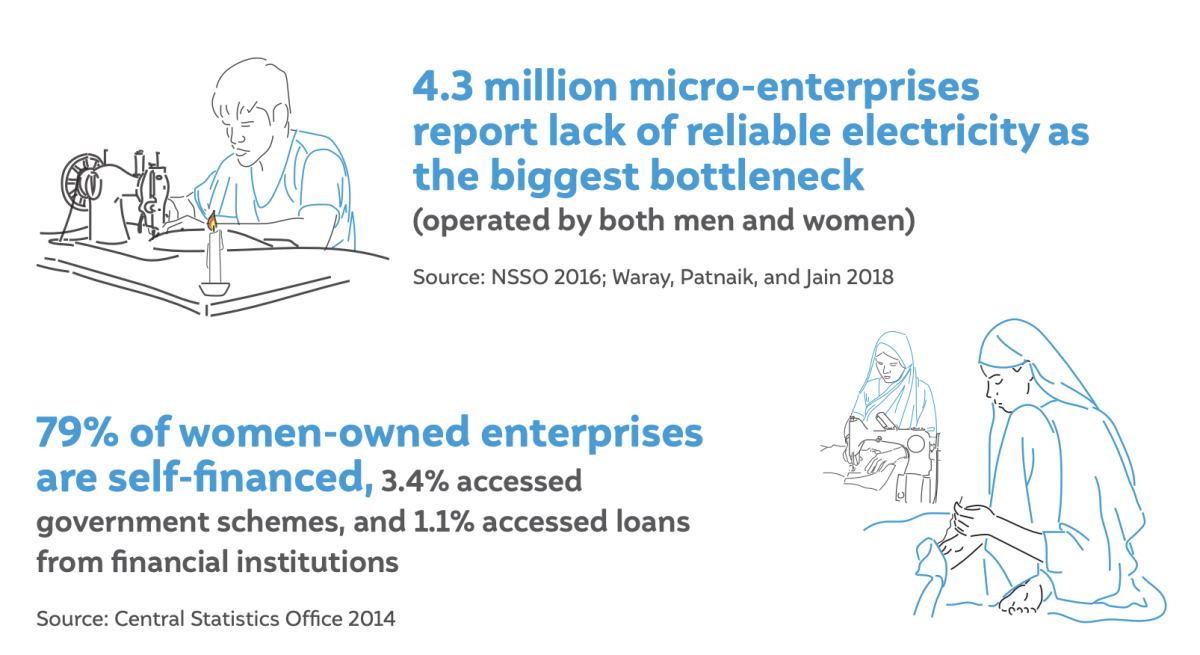

Women comprise almost half of the self-employed farmers (National Statistical Office 2020) and own over one-fourth of the proprietary micro, small, and medium enterprise (MSME) units in the country (MoMSME 2020). And access to electricity can drive economic and social development by increasing productivity, enabling mechanisation (Pueyo and Maestre 2019), and reducing drudgery in economic activities.

Women traditionally have had limited access to mechanisation compared to men, even within family-based occupations, owing to the gendered socio-economic barriers that deprive women of decision-making control and access to credit in economic activities. Lack of mechanisation compels women to operate at low levels of productivity and high levels of drudgery. This restricts their income and available time preventing them from investing in their capabilities and families more meaningfully.

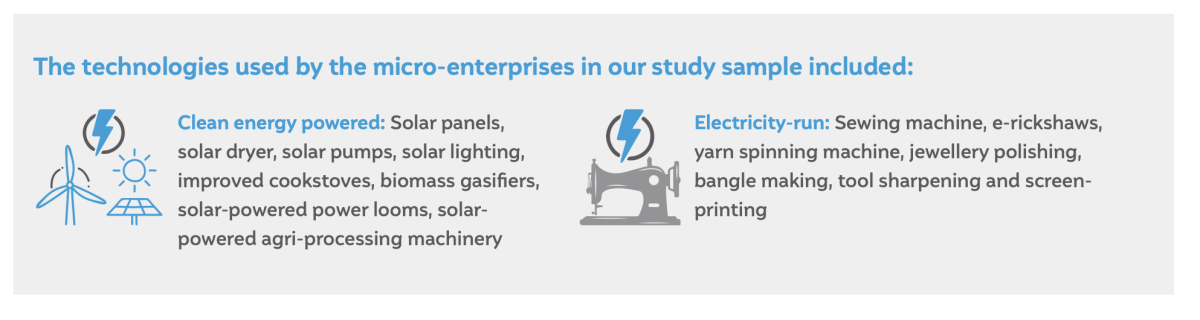

Access to decentralised renewable energy (DRE) and energy-efficient innovations (such as sewing machines, milk-chillers, milking machines, motorised pottery wheels, charkha and weaving machines, and solar pesticide sprayers) have the potential to improve productivity and reduce drudgery in livelihood activities for both men and women (Waray, Patnaik, and Jain 2018). DRE-enabled solutions are also easier to use and more affordable. However, traditionally more women are involved in manual work than men so they could benefit more from mechanisation, especially self-employed women.

Improving women’s productivity and incomes through reliable and affordable access to energy for economic activities could directly contribute to achieving Sustainable Development Goals 5, 7, and 8 simultaneously. Furthermore, as women happen to be an integral part of livelihood activities, their access to access-to-energy companies could help expand markets and achieve scale by working with other women across the value chain as producers, customers, and suppliers of energy products.

Focusing on women-led micro-enterprises as users or potential users of clean energy appliances, this study explores the impediments women entrepreneurs face with the aim to i) increase support for women leading energy access businesses in India, ii) increase participation of women in the clean energy value chain, and iii) increase uptake of cleanenergy-powered livelihood equipment by women micro-entrepreneurs.

As we discuss barriers and proven solutions with the potential to scale, we emphasise on access to finance and government schemes and services to help women micro-entrepreneurs scale and use clean-energy-powered livelihood technologies in their business.

Enterprises, donors, financiers, incubators and policymakers in the clean energy sector: The report discusses how energy enterprises have supported mechanisation for women in rural India. For enterprises in the energy sector, it offers ideas and data for mainstreaming the gender lens in their business and experience gains from it. The report informs other stakeholders (donors, policymakers, financiers, and incubators) on how to support such enterprises, include women as end-users of energy products, and address the barriers presented within the realm of social norms, market approaches, and government policies.

Non-profits, donors, and policymakers working on livelihoods and women’s economic empowerment initiatives: The report offers insights into new business models at the intersection of mechanisation, energy access, and women’s livelihoods. As an intermediary, energy is uniquely positioned to create impact across sectors and demonstrate ways of inclusion. For organisations working across various livelihood sectors, the report offers ideas on working with energy enterprises to mechanise activities and access new financing forms to enable it.

We primarily focus on women as end users of energy products (own account workers/ self-employed/micro-entrepreneurs), who are mostly dependent on debt (loan) and sales to expand their business.1 Typically categorised as micro-entrepreneurs, these are self-employed women who could potentially be buyers and users of clean energy equipment or machines in their business.

We adopted a mixed method for data collection, in partnership with Jagriti Yatra and SEWA Bharat, to understand the challenges women micro-entrepreneurs face in accessing finance and utilising schemes and policies.

We analysed the barriers to scale and opportunities for women micro-entrepreneurs through society, market, and state triad (Pal et al. 2020) to identify overlapping impact and suggest interventions by key stakeholders to enable clean energy enterprises and micro-enterprises to achieve their goals.

We describe the involvement of women entrepreneurs across the energy value chain and deep dive into the barriers and support available across a range of aspects.

Women founders of clean energy enterprises

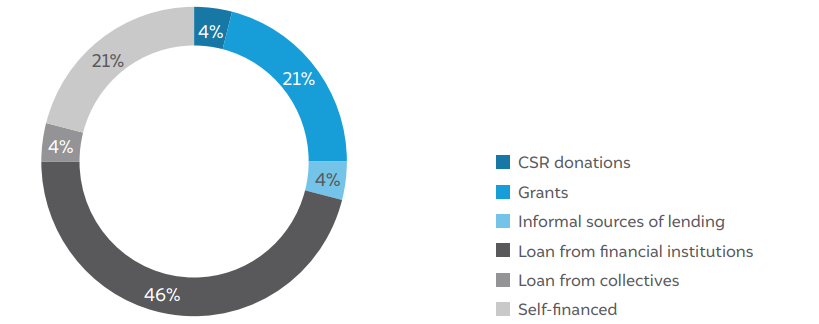

Grant and debt funding remain an essential source of finance for most early-stage women entrepreneurs in the energy sector. While the majority of women-owned enterprises3 have received some form of grant (from donors or incubators), less than 50 per cent of the clean energy enterprises have preferred debt funding, whereas very few have sought equity. We find that the majority of entrepreneurs relied on personal resources for initial financing. About 25 per cent of women entrepreneurs reported accessing available government schemes.

Customised approach to mentorship and technical and financial assistance (based on enterprise’s business stage) is of value for all entrepreneurs. Still, with a strong gender lens, incubation and acceleration programmes can benefit women more than gender-neutral approaches.

Women employees or value chain partners in clean energy enterprises

Women are significantly underrepresented as employees in clean energy enterprises, particularly in technical roles like product design and engineering that could improve products’ uptake and usability (Martin and Glinski 2019). In our interviews, most entrepreneurs reported having women in office-based roles. In technical roles like supply chain management, manufacturing, and installation, only male employees are preferred.

Women are also involved in the clean energy sector (1) as product distributors and sales agents and (2) as workers or suppliers in agriculture and textile value chains. Women as last-mile distributors of energy products have to travel to nearby villages, and they are primarily dependent on other family members for mobility. However, they earn a commissionbased income, and the employer ensures the market is big enough to make a good income. As workers and suppliers, women are supported with guaranteed market linkage, flexible work, access to technologies through a grant model or long-term loans facilitated by partner organisations or the clean energy enterprises offering margin money for loans.

Women-led micro-enterprises as users/customers of energy products and services

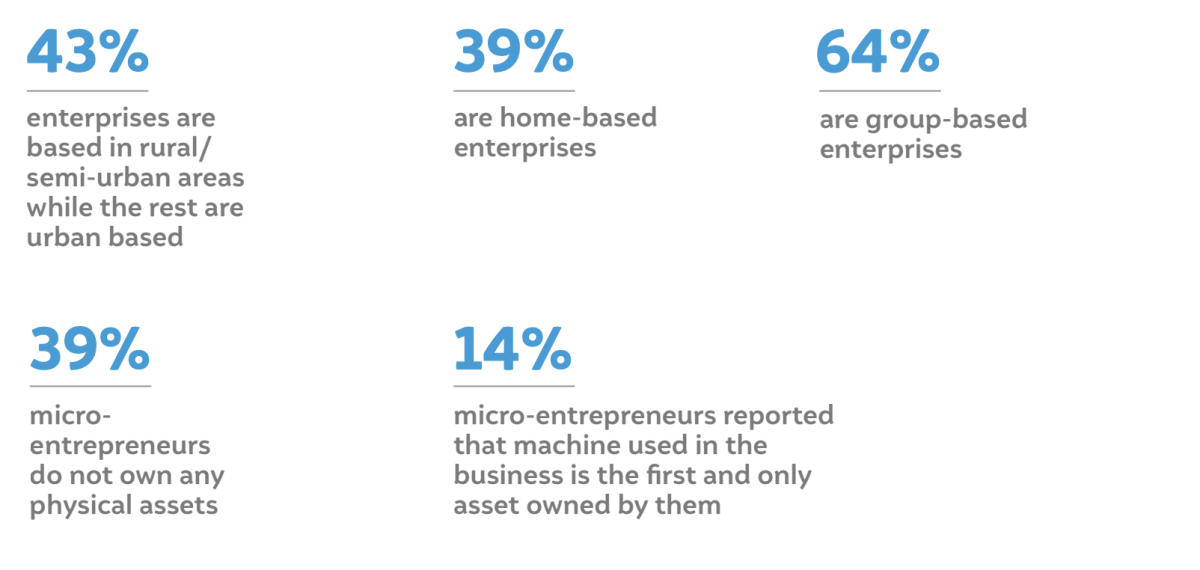

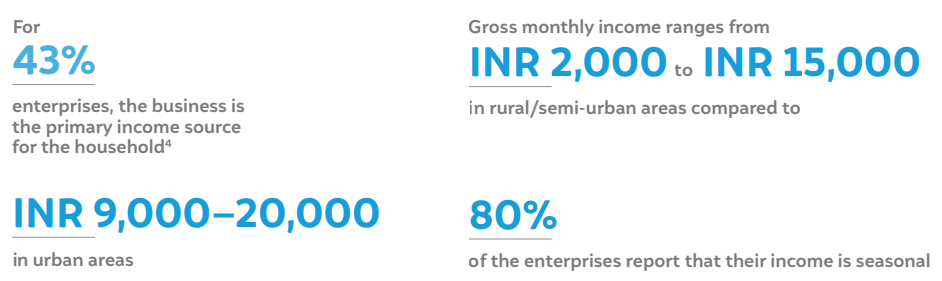

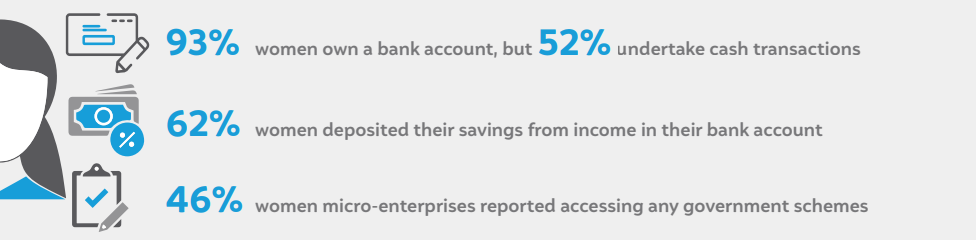

Women micro-entrepreneurs are self-employed women who could potentially be buyers and users of machines powered through electricity or renewable energy. In this study we primarily focus on women micro-entrepreneurs. This section highlights key characteristics of women micro-entrepreneurs in our sample using data from the CEEW micro-entrepreneur survey.

Source: CEEW analysis; Data: CEEW micro-entrepreneur analysis

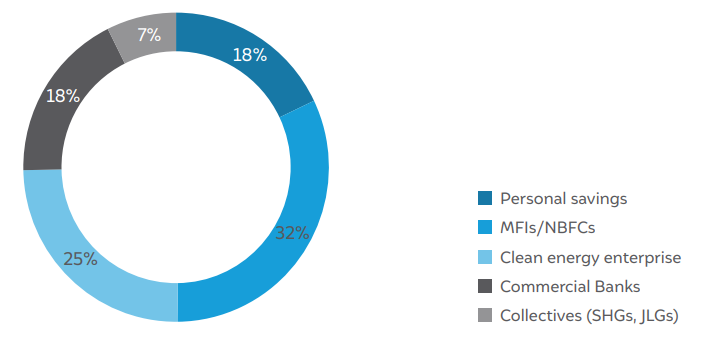

Figure ES2 Loans are the most prominent source of finance for procuring for the machine

Source: CEEW analysis; Data: CEEW microentrepreneur analysis

Sample size: 28

Source: CEEW analysis; Data: CEEW micro-entrepreneur analysis

Figure ES3 Loans and clean energy enterprises are the primary source of financing to use DRE-powered products

Source: CEEW analysis; Data: CEEW microentrepreneur analysis

Sample size: 28

We note two predominant forms of business models through which clean energy enterprises engage with women micro-entrepreneurs: product-based approach and value chain-based approach.

Product based approach

The clean energy enterprise focused on sales and service of the product through partners or micro-entrepreneurs/collectives. Through this model, many enterprises who primarily worked with male collectives or micro-enterprises have reached women micro-enterprises with their solutions.

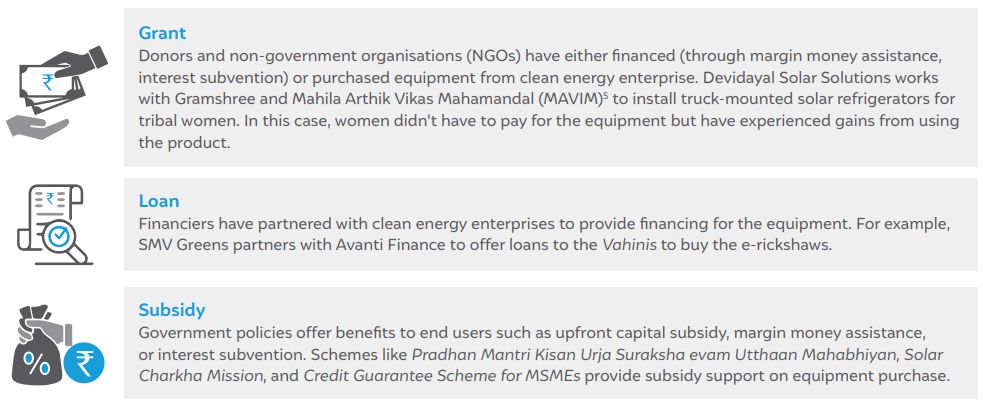

Examples: Alto Precision utilises the State Rural Livelihoods Mission scheme to install agroprocessing machinery for women and Devidayal Solar Solutions works with Gramshree or Mahila Arthik Vikas Mahamandal to install truck-mounted solar refrigerators for tribal women.

Value chain approach

The clean energy enterprise is involved in the business value chain for the end user. The product is part of the offering. Training, financing, product deployment, and market linkage are also provided by the enterprise. This approach helps the enterprise in sustainable growth through repeated customers and closer engagement with micro-entrepreneurs.

Examples: S4S Technologies producing solar dryers has ventured into the food processing value chain and SMV Green Solutions supports women e-rickshaw drivers.

Within the product-based approach and value chain-based approach, women-led microenterprises access technologies through one or a combination of the following financing options:

We acknowledge a variety of initiatives targeting women’s livelihoods in the domain of society, market, and state, which have enabled clean energy enterprises and women-led micro-enterprises to achieve scale and impact. However, we note that barriers of financing, access to schemes, and policy design need well-targeted support to truly create gender-transformative impact through energy access for women founders of clean energy enterprises, women employees, and value chain partners and end users of energy products and services (women-led micro-enterprises).

Some interventions by clean energy enterprises have moved from being gender neutral to gender-sensitive. Still, there is an opportunity for them to become gender-transformative by investing in women and equalising gender relations in the long run. Current interventions by businesses, donors, policies, and financiers do not always aim to engage with the gender dynamics between women and men in ways that create sustained impact and avoid unintended consequences. While one could argue that it is not always possible for a business to engage deeply with gender relations, we have listed examples where businesses have engaged with barriers for women within households and communities through their marketing, sales or financing strategy, complemented by their local partners’ efforts. To support this endeavour, government policies and schemes would need to be gender-sensitive in their design and implementation guidelines, and not just in sectors with greater livelihood opportunities for women but also in other sectors to encourage greater participation of women. Through more inclusive product design, financing support, scheme design and implementation, and social safety nets for women, the energy access for livelihoods sector would be able to achieve greater scale for themselves and depth of impact.

Closing the gender gap in the economy would entail better targeting of funding for women and integration of gender-inclusive strategies in all sectors, including the energy sector. As of 2017–18, the energy sector, despite being well funded, has had around 10 per cent of the total funding focused on gender equality over the past years. With an optimistic business case for the sector, there is an opportunity to better integrate a gender perspective in energy programmes, with the understanding that enhanced access to reliable and affordable modern energy is crucial for women and girls (OECD GENDERNET, 2020). In the current economic recovery context post COVID-19, it is important that governments, donors and investors work to improve productivity and reduce the drudgery for women-led micro-enterprises, which can contribute to the rebuilding of the economy through better incomes for the household and generation of employment.

We hope this report is able to shed light on the potential strategies that could be adopted and scaled in the energy sector to support women entrepreneurs across the value chain by addressing the barriers of financing and access to policies. We also hope that the recommendations listed in the document are able to guide key actors in the sector—clean energy enterprises, donors, financiers, accelerators and incubators, policymakers, and entrepreneurs themselves across all stages of growth—to accelerate the pace and scale of interventions that could impact and improve productivity as well as incomes for women’s micro-enterprises in India.

1 A detailed assessment of barriers and opportunities for women-led clean energy enterprises has already been covered in Martin and Glinski (2019).

2 Refer to Annexure I for the detailed list of stakeholders interviewed.

3 About 75 per cent of the clean energy enterprises we interviewed were women-owned, operational for about four years.

4 In such cases, often-family members are also involved in running the business.

5 MAVIM is Maharashtra’s state ‘Women Development Corporation’, established in 1975 and registered under Companies Act, Section 8A, as a not-for-profit company.