Suggested citation: SEI & CEEW (2022). Stockholm+50: Unlocking a Better Future. Stockholm Environment Institute. DOI: 10.51414/sei2022.011

This report, in collaboration with Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI), is an independent scientific report for the UN international meeting, ‘Stockholm+50: a healthy planet for the prosperity of all – our responsibility, our opportunity’. Based on a synthesis of scientific evidence and ideas, it identifies concrete actions under three broad shifts: redefining the relationship between humans and nature; ensuring lasting prosperity for all; and investing in a better future. The report analyses the barriers to change and underlines the ways to unlock progress by improving coherence, accountability, solidarity and a renewed multilateralism. It highlights that these shifts require the involvement of multiple actors – including governments, multilateral institutions, private sector and individuals – and emphasises on reforming the global governance landscape. It makes recommendations for reform and new thinking on complex issues of finance, technology, lifestyles and others, all of which need bold action for a better future.

Fifty years since the 1972 UN Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm, the world has changed in alarming ways. Stockholm+50 is an opportunity to move beyond gridlocked international negotiations. It is a chance to reshape national and global interactions, deliver equity and amplify a global movement for a more caring world. This report is a contribution to support and enable a legacy that unlocks a sustainable future for all humans and the planet.

Looking back at the past 50 years, the world has changed in many ways – but not in the direction called for at the UN Conference on the Human Environment, held in Stockholm in June 1972.

Today we commemorate that conference at the UN international meeting ‘Stockholm+50: a healthy planet for the prosperity of all – our responsibility, our opportunity’. The context in which the Stockholm+50 international meeting takes place is alarming: we face intertwined crises of the state of our planet and extreme inequality among people and societies. The Covid-19 pandemic continues to slow or reverse progress. And geopolitical shifts highlight our interconnectedness and vulnerabilities more than ever.

At the 1972 gathering in Stockholm, heads of state committed to taking responsibility for protecting and promoting human and environmental health and well-being.

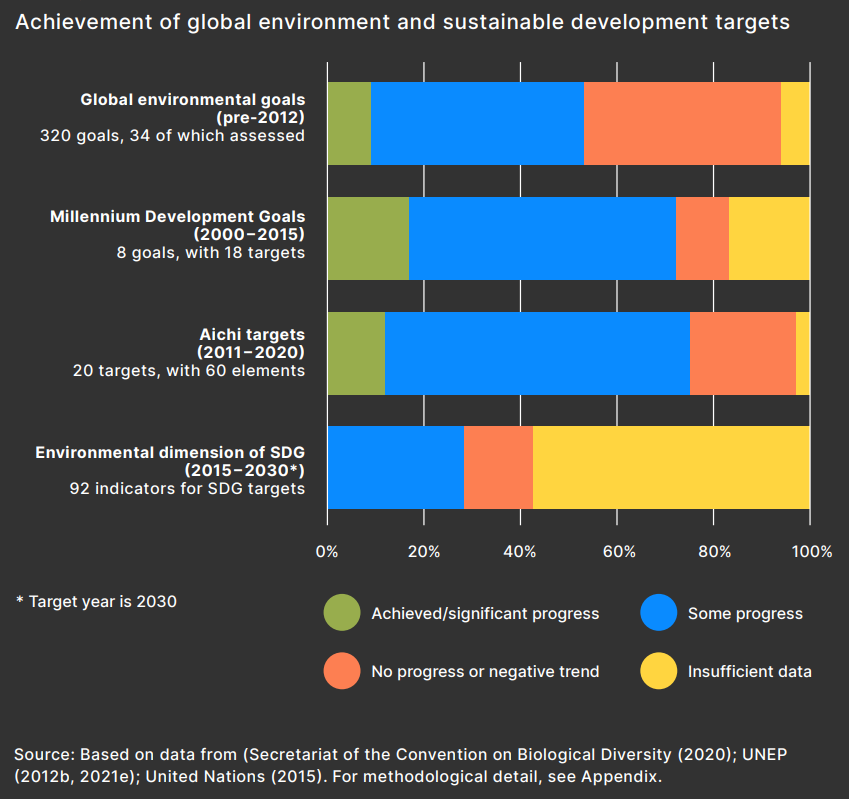

Today, we can see that the track record to deliver on the ambitions of half a century ago has been poor. Our assessment of the framework for environmental action conceived in 1972 shows that, while knowledge, goals and agreements have only increased, international supporting measures – financing, technical cooperation and organization with strong mandates – remain too weak to deliver on the goals and lead to actions in accordance with our knowledge. So far, only about one-tenth of global environmental and sustainable development targets have been achieved, and outcomes and impacts for a healthier planet remain insufficient.

Humans are causing unprecedented change to the global environment and are risking tipping points with major and irreversible changes in our lifetimes. Climate change has already caused widespread adverse impacts to nature and people, and limiting global warming to 1.5°C is beyond reach without immediate, rapid and large-scale reduction of emissions. Biodiversity and ecosystems are deteriorating worldwide, and goals for conserving and sustainably using nature cannot be met by current trajectories.

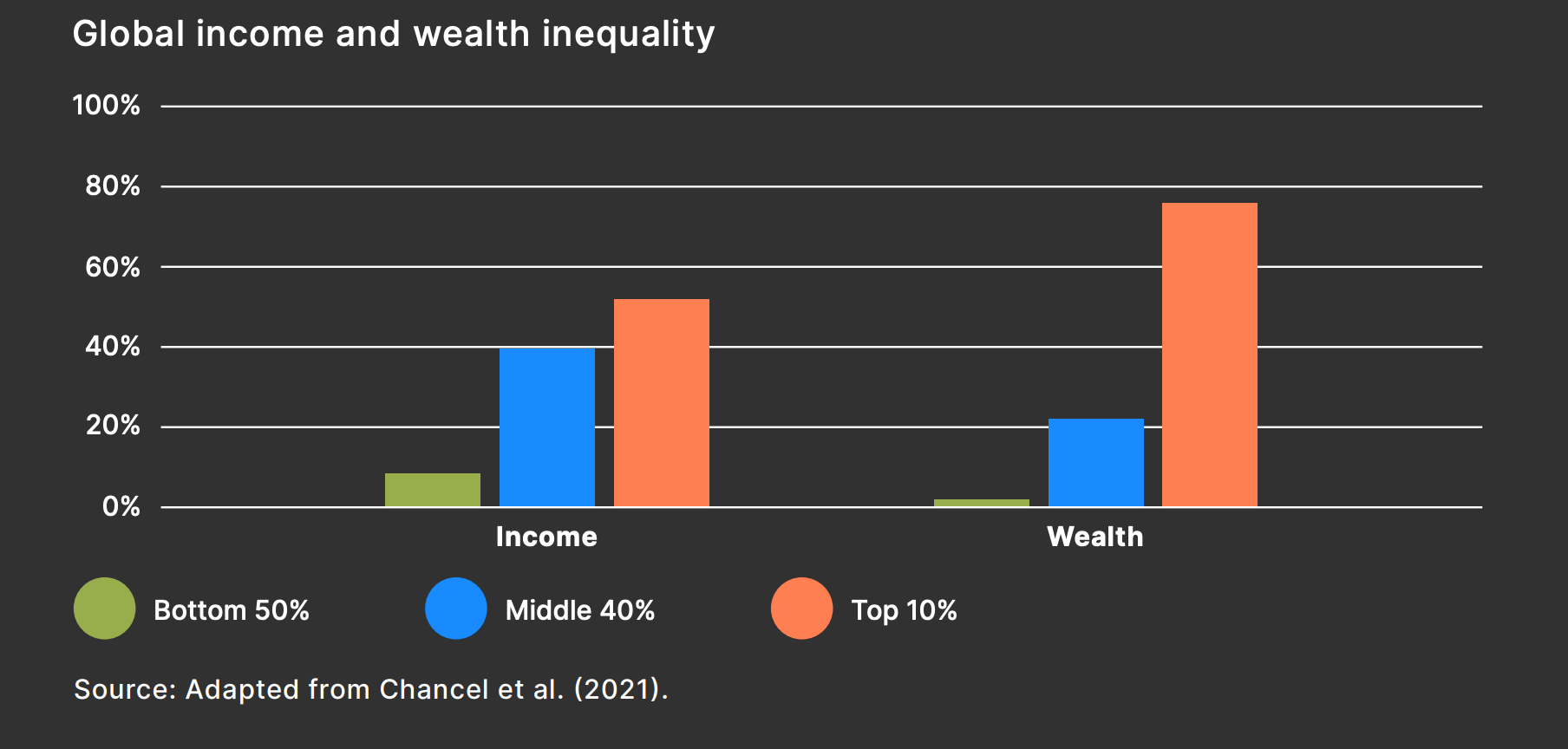

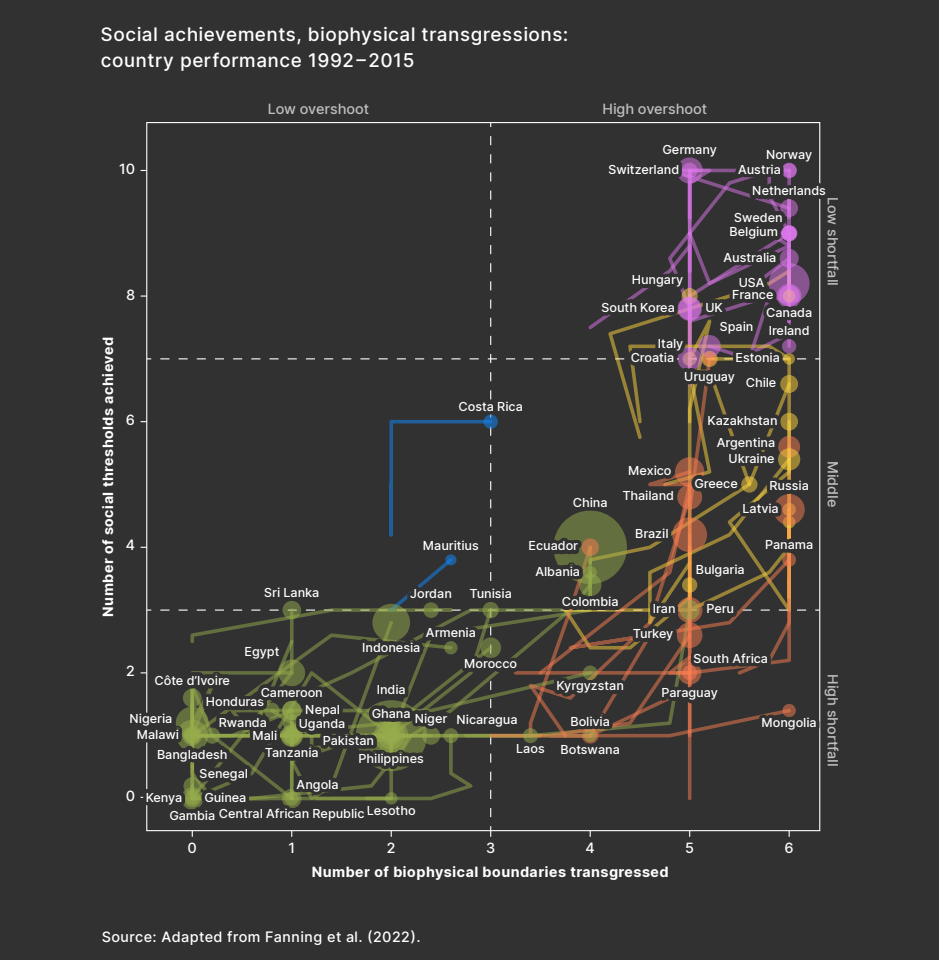

Unsustainable production and consumption patterns put a healthy planet and sustainable development at risk. The use of natural resources has more than tripled from 1970, continues to grow. The use of these resources and their benefits is unevenly distributed across countries and regions. The poorest half of the global population owns barely 2% of the total global wealth, while the richest 10% owns 76% of all wealth. Compared to 1972, overdevelopment and affluence, rather than underdevelopment and scarcity, are the drivers of unsustainable resource use. Currently, no country is delivering what its citizens need without transgressing the biophysical planetary boundaries.

The inequity among people and places in both causing deterioration and suffering from its impacts is high. The poorest half of the global population contributed 10% of emissions; the richest 10% of the global population emitted more than half of the total carbon emissions during 1990–2015. Meanwhile climate disaster–related death tolls of potentially exposed populations during 2000–2017 indicate 16 deaths per million for high-income groups, compared to 60 per million for low-income groups. The social and economic costs of inaction are predominantly borne by the poorest and most vulnerable in society, including Indigenous and local communities, particularly in developing countries.

High-income countries must drastically reduce their footprints, especially in light of their cumulative footprints over time, to avoid closing development pathways for low-income countries and future generations. A person born today may live in a world that is on average 4°C warmer than today, in which 16% of species would be at risk of extinction, and their exposure to heatwaves during their lifetimes is up to seven times that of a person born in 1960.

Today, our modes of consumption, production and finance are leading to environmental changes that undermine hard-won development gains. But a ‘low-carbon life’ can and should be a good life – and one that is easily accessible to all. The coming decade is crucial to redirecting our trajectory toward a sustainable and just future.

The framework for environmental action conceived in 1972 has delivered political and scientific activity, but the outcomes remain insufficient. The world has already agreed on a vision for sustainable development and common future – Agenda 2030. This vision still needs to come to fruition.

There is growing momentum for change. Public opinion reflects the sense of urgency and indicates willingness to change lifestyles. Youth worldwide are both exercising and demanding more agency to fight climate change, environmental degradation and inequity. Key technological development and uptake has occurred faster than anticipated, and evidence builds of the many wins and co-benefits from taking climate and sustainability action at a policy level.

We need to compress timescales for decision-making and implementation of key investments and infrastructure, without compromising values of democratic legitimacy and inclusiveness. Simultaneously, timescales must be extended in decision-making to avoid intergenerational discrimination and committing ourselves to unsustainable infrastructure, and to enable bold, long-term transformation.

We have the means to act; we need incentives that favour actions over commitments. We are better equipped than ever to make 2022 a new watershed moment for pursuit of our sustainable future on Earth. If we unlock change now to enable delivery on a compelling post-2030 vision, we won’t need a Stockholm+100.

With Stockholm+50, we must unlock change that is substantial and systemic. A sustainable world should provide a good quality of life that is broadly shared and can be maintained indefinitely into the future.

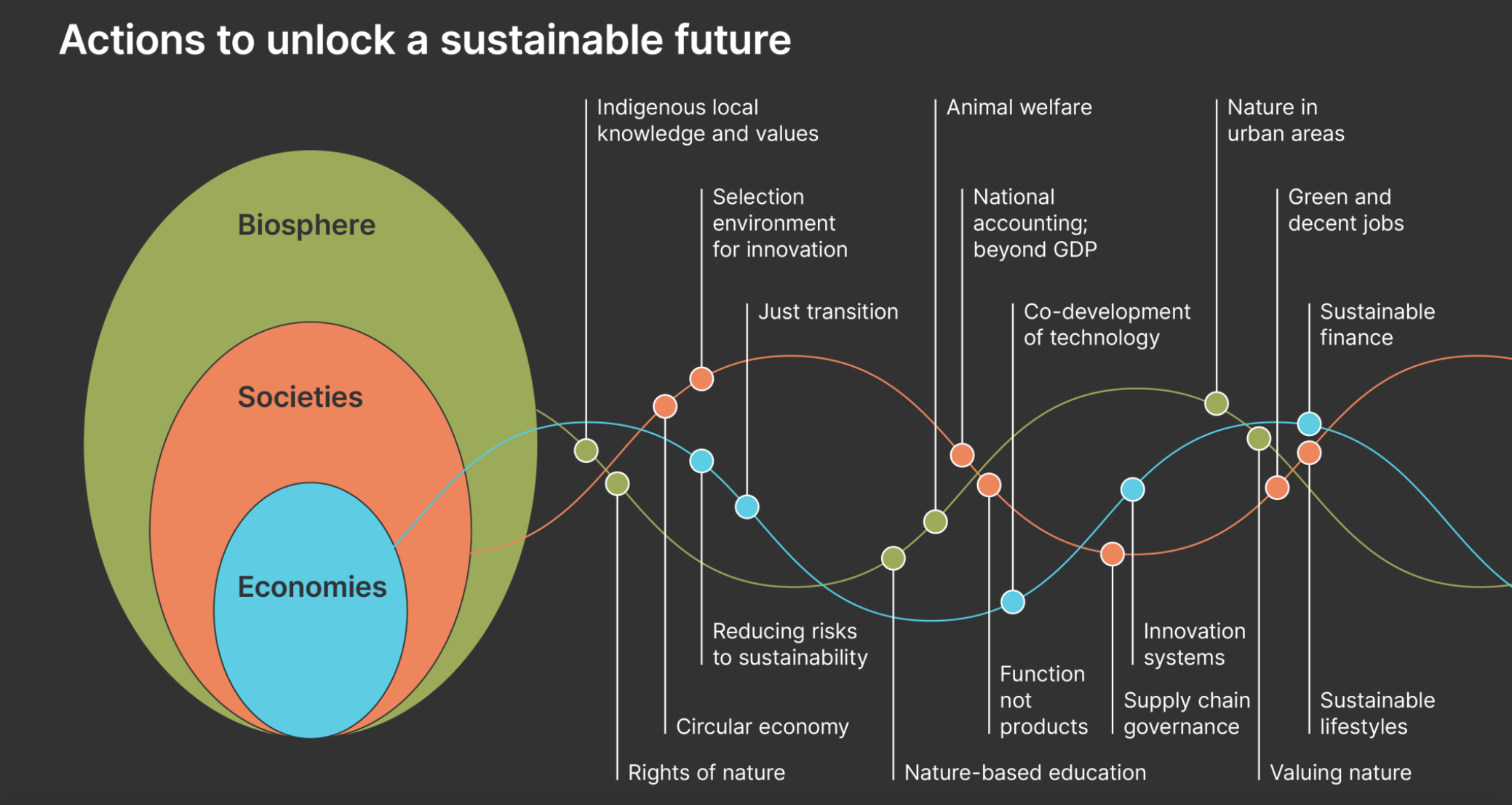

Based on a synthesis of scientific evidence and ideas, we identify concrete actions under three broad shifts that would take us to a more sustainable development. If they are initiated now, they can accelerate change, large and small, for the long term.

The past 50 years – and even the past 5 years – have seen huge losses and degradation of nature globally. Humans have altered 75% of the planet’s land surface, impacted 66% of the ocean area, and destroyed (directly or indirectly) 85% of wetlands. Many societies value nature as an instrument, something to be used for resources; that perspective has driven the ecological decline of the past half-century and beyond. An instrumental valuation often underpins policies and economic structures that in turn shape behaviour and social norms at the individual level. Repairing the relationship between people and nature will require redressing this imbalance, by placing more emphasis on the intrinsic and relational value of nature. Such a shift would be transformative, requiring deep changes across societies, economies and communities: how we live in our cities, how we produce food, how and what we learn, and the knowledge and rights that inform our choices.

Calls to action

The amount of natural resources extracted by humans globally each year has tripled since 1970. High-income countries have consumed most of these resources, with CO2 consumption footprints that are more than 13 times the level of low-income countries. Ensuring lasting prosperity for all and bringing emission and resource footprints within ecological limits requires a complete rethink of our ways of living, and a shift in social norms and values that drive human behaviour. It requires redefining prosperity at all levels in society and economy.

Calls to action

To ensure prosperity for all and repairing our relationship with nature, investing in a better future is necessary. Today, we have the paradoxical situation of a massive amount of capital ready for sustainability investments, yet persistent funding gaps in low-income countries.

The SDG funding gap globally has been estimated at USD 2.5 trillion by the OECD, while UNCTAD estimates that the value of sustainability-themed investment products in global capital markets increased by more than 80% from 2019 to 2020. Action is needed to not just mobilize capital for sustainability, but to ensure sufficient levels at lower costs, supporting allocation to places and sectors in need, and transitioning out of unsustainable practices and capital goods.

Calls to action

Progress in these action areas are steps on our path to sustainability, that would activate and accelerate the three shifts we urgently need now and hopefully lead to systemic changes. At the same time, we also need to address the systems and infrastructures we have inherited, in processes that will unfold more slowly. The governance context in which we understand these barriers has changed since 1972. Our world today has shifted even more toward multi-level, polycentric governance, where we have a complex set of actors, institutions, and sources of agency.

Decision makers and policymakers, at all levels, should dismantle barriers of political incoherence, weak multilateralism, limited accountability, and unreformed international finance, which prevent our acceleration towards sustainable and equitable societies.

We hold the keys that can unlock opportunities for change. Setting small and large processes in motion today can allow us to progress on the goals that were established 50 years ago, at the first UN meeting to bring together humans and the environment.

We repeat the same call made in the 1972 UN Stockholm Declaration for a new watershed moment in 2022:

A point has been reached in history when we must shape our actions throughout the world with a more prudent care for their environmental consequences. Through ignorance or indifference we can do massive and irreversible harm to the earthly environment on which our life and well-being depend. Conversely, through fuller knowledge and wiser action, we can achieve for ourselves and our posterity a better life in an environment more in keeping with human needs and hopes.’

Rethinking Ocean Governance in an Era of Climate Urgency

Trust and Transparency in Climate Action

Operationalising the Loss and Damage Fund to Address Climate Impacts

Sustainability-driven Non-tariff Measures