Suggested citation: Rahman, Anas, Shalu Agrawal, and Abhishek Jain. 2021. Powering Agriculture in India: Strategies to Boost Components A & C Under PM-KUSUM Scheme. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

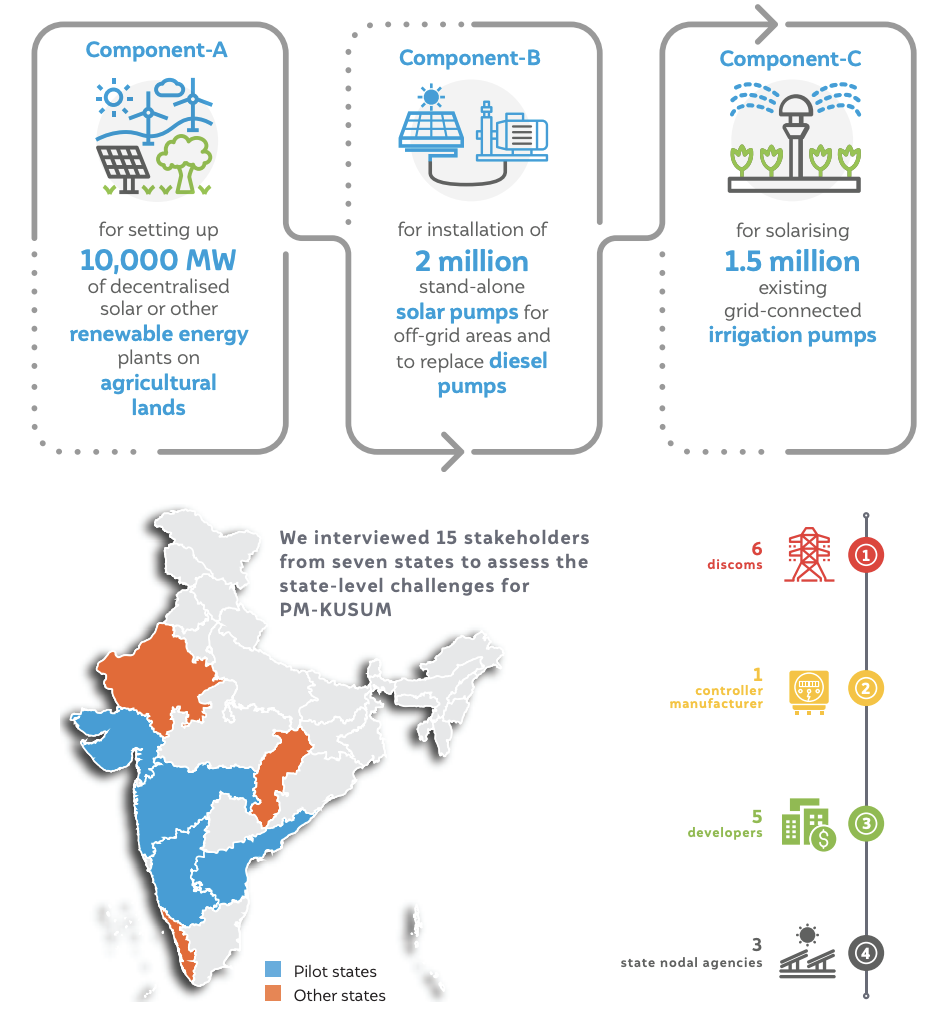

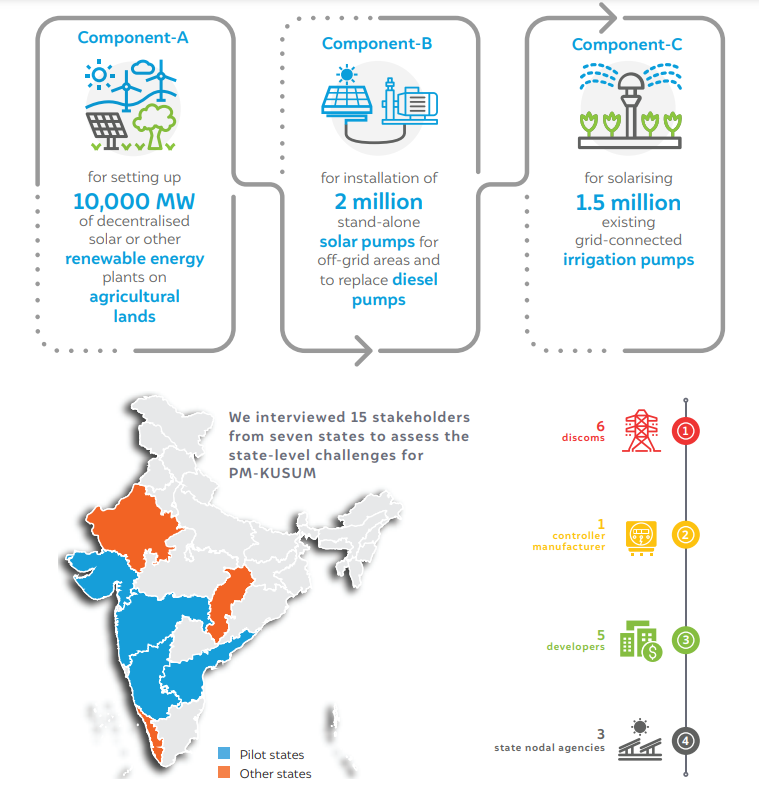

This study intends to help unlock the potential of two solarisation models - solarisation of rural electricity feeders and solarisation of individual grid-connected pumps - to power India’s irrigation needs. These two models are promoted under components A and C of the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Urja Suraksha evam Uthhan Mahabhiyan (PM-KUSUM) scheme launched by the Government of India in 2019. However, these components have seen only a few takers among the states and power distribution companies (discoms). Based on in-depth consultations with representatives of discoms, state nodal agencies of renewable energy, and private developers and manufacturers across seven Indian states, the study discusses the challenges hindering the components’ uptake and solutions to address the same.

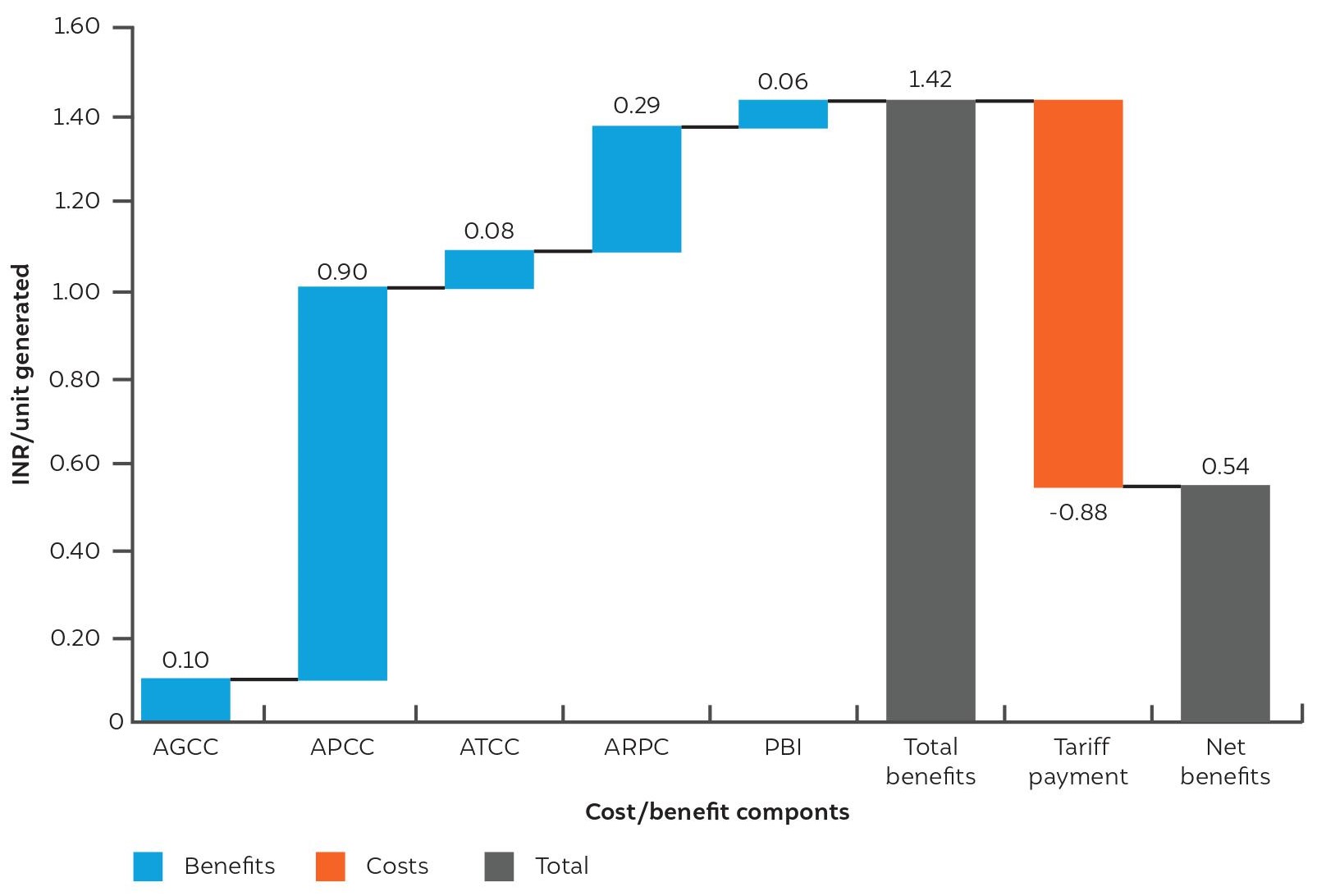

Component-A: Decentralised solar plants on farmlands

Under this model, farmers can set up solar or other renewable power plants on their land (directly or by leasing out land to developers), and the discom would purchase power from them.

A Karnataka discom would gain a net benefit of INR 0.54 for each unit produced from the Component-A power plant over 25 years

Source: Authors’ analysis using VGRS framework developed by Kuldeep et.al. (2019)

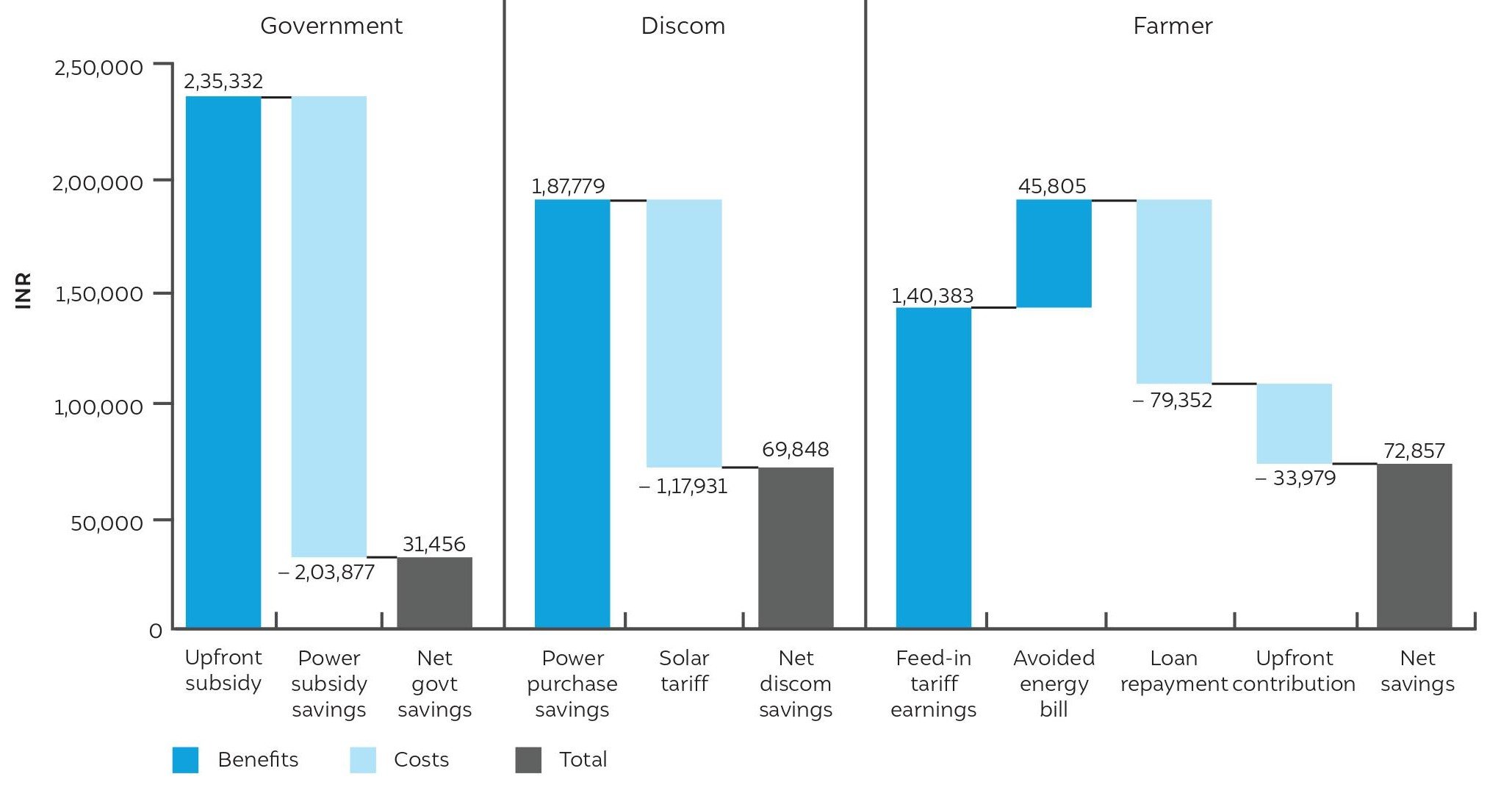

Component-C: Grid-connected solar irrigation pumps

Under this model, farmers with existing grid-connected pump sets are eligible for subsidies to solarise their connections, and sell any excess power to the discoms at a predetermined tariff.

All three stakeholders would theoretically benefit from Component-C

Source: Authors’ analysis

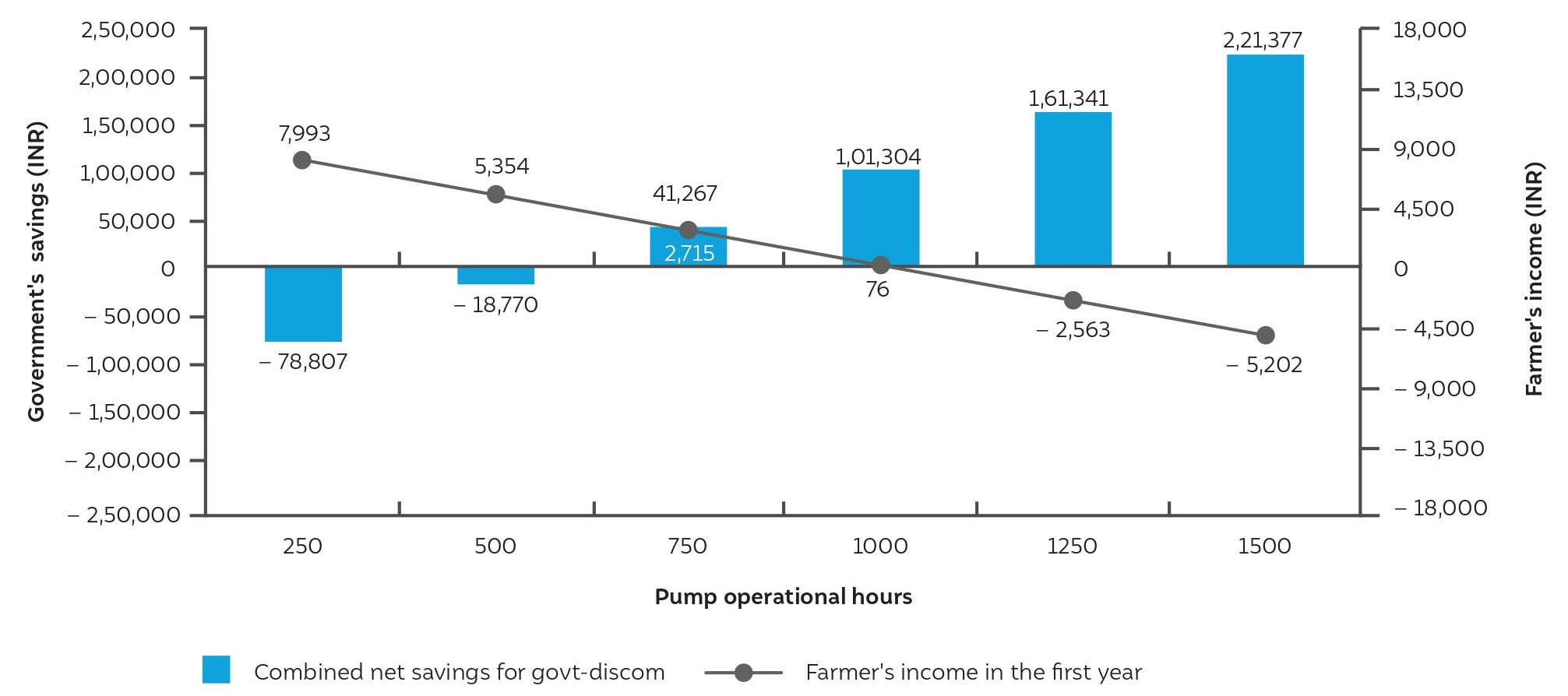

There is a strong negative correlation between farmer’s income and combined net savings for the government and discom

Source: Authors’ analysis

To stimulate the uptake of Component A, we recommend the following measures:

To support the off-take of grid-connected solarisation model under Component C, we propose the following:

The Government of India launched the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Urja Suraksha evam Utthaan Mahabhiyan (PM-KUSUM) scheme in 2019 to improve irrigation access and farmers’ income through solar-powered irrigation. Under its components A and C, the scheme aims to promote innovative models for solar-powered irrigation by setting up solar power plants on agricultural land, and solarising existing grid-connected pumps, respectively. These components intend to support farmers to be net energy producers and earn an additional income. Concomitantly, the state governments are expected to reduce their agriculture power subsidy bills, while the discoms procure low-cost solar power sourced closer to the consumers through these models.

Notwithstanding the pandemic-related challenges, with almost half the scheme’s target period already over, these components have not taken off in most states. Only the Rajasthan government has offered letters of award for projects under Component-A. Rajasthan is also the only state that has begun installing grid-connected solar pumps under Component-C, that too on an experimental basis. In contrast, Component-B of the scheme promotes stand-alone solar pumps and is progressing well across many states. Therefore, this study investigates the reasons behind the slow uptake of the components A and C of the PMKUSUM scheme and proposes solutions to overcome the key barriers.

We do so by capturing the experience of seven Indian states in the implementation of the components A and C of the PM-KUSUM scheme and related previous pilots. Our findings are based on detailed interviews with 15 key informants across power distribution companies, state nodal agencies, developers, system integrators, and manufacturers. During the semistructured interviews, which lasted for 45-90 minutes, we focused on identifying potential administrative, regulatory, financial, operational, and technical challenges hindering the scheme’s rollout. We also discussed possible solutions to address these challenges. In addition, we conducted a scenario-based economic analysis to assess the economic viability of Component-C for farmers, the power distribution companies (discoms), and the government. Below we summarise our key findings and recommendations.

Under Component-A, farmers can set up solar or other renewable power plants on their land (directly or by leasing out land to developers), and the discom would purchase power from them. Most discom respondents were enthusiastic about this component due to its potential to reduce the power-purchase cost, but shared concerns about several implementation challenges, including surplus of contracted generation capacity. Unattractive tariffs for developers, delays in land leasing/conversion and inability of farmers to mobilise equity or debt finance also emerged as key challenges. To overcome these challenges, we propose the following recommendations for Component-A.

1. Modify the scheme timelines to enable the inclusion of Component-A in discoms’ power-purchase planning

Many discoms are not in a position to benefit in the short term from the component due to surplus contracted capacity and low variable cost of power from conventional power plants. Many are not in a position to shoulder the additional burden for long-term benefits, a situation further exacerbated by the pandemic-induced stress on discoms’ finances. Savings from renewable purchase obligation (RPO) fulfilment also depends on the discoms’ power-purchase plans and the level of enforcement of RPO regulations. The Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) should modify the timelines for the scheme to enable the discoms to align the component with their power-purchase planning and gain maximum benefit from the component. The central government should also strengthen the RPO regulations enabling the discoms to plan for RPO fulfilment through Component-A power plants.

2. Reduce risks and improve the competitiveness of decentralised power plants

The MNRE should study the impact of new customs duty on the cost competitiveness of small-capacity power plants and take appropriate measures to mitigate the associated disadvantages. The MNRE, in consultation with the Forum of Regulators (FOR), should also prepare a guidance note for the state SERCs to standardise an approach for tariff for Component-A power plants considering the factors like limited economies of scale, lower DC-to-AC conversion efficiency, etc. Two key risks concerning the deployments under Component-A are grid unavailability and counter-party risk. The MNRE should strengthen the compensation clauses in grid unavailability and put the onus on the discoms to ensure a minimum grid availability. The discoms should be penalised in the event of failure to honour the power-purchase agreements (PPAs) to reduce the counterparty risks for the developers.

3. Undertake broader policy reforms to address the bias against distributed solar power plants

Under the current Inter-State Transmission System (ISTS) regulations, solar power plants are exempt from transmission charges, and no transmission losses are accounted for towards solar generation. This statute, which was brought in over a decade ago to promote the solar power sector, has unintendingly favoured large utility-scale solar power plants in a few states with high generation potential, like Rajasthan, over the distributed solar plants. The former offers cheaper rates due to favourable generation conditions and the discoms do not have to bear the inter-state transmission costs, thus reducing the effective cost of power by about INR 0.5-2.2 per kWh (Menghani 2021). The central government should do away with this archaic statute and initiate policies favouring distributed power plants if Component-A or similar schemes are to succeed.

4. Streamline land regulations to ensure smooth implementation

State regulations concerning land leasing and land conversion from agricultural to nonagricultural uses have been a critical barrier in the scheme’s implementation. Some states prohibit the leasing of agricultural lands for non-agricultural purposes. Even states like Karnataka, with provision for ‘deemed diversion’ of agricultural land for solar projects, have witnessed administrative delays in this regard. Implementing agencies should work closely with the state revenue department to identify and address these challenges.

5. Adopt innovative models to overcome financing challenges with farmer-owned power plants

Usual means of project financing for developers are inadequate for farmer-owned power plants for two reasons. One, farmers are not able to raise/contribute the 30 per cent equity for the power plant. Two, in the absence of any track record as a developer, they cannot access loans from banks without collateral. Banks do not take agricultural land as collateral for non-agricultural purposes. State nodal agencies (SNAs) need to work with financial institutions to try innovative models such as the farmer-developer specialpurpose vehicle (SPV) piloted in Karnataka.

6. Ensure inter-departmental coordination to mitigate any issues in the planning and implementation phases

Multiple agencies like the discoms, SNAs and revenue departments have roles to play at different stages of implementing this component. States should form a PM-KUSUM steering committee, led by the implementing agency, with state-level representatives from all the concerned departments. Such an arrangement can anticipate any interdepartment coordination issues in the planning and implementation phases and address them

The Component-C of the PM-KUSUM scheme aims to support the solarisation of the existing grid-connected pumps through two models – individual-pump solarisation and feeder-level solarisation. In this study, we focused only on the individual solarisation model as many of the challenges and issues concerning feeder-level solarisation are akin to Component-A.

We find that most stakeholders are not enthusiastic about this model. The discom representatives unanimously anticipated difficulty getting farmers to pay the upfront contribution, as most target farmers already benefit from free or highly subsidised power. In the absence of upfront beneficiary contribution from the farmers, the economic viability of the component is uncertain. The alternative financing options – either increasing the farmer’s loan component or increasing the government subsidy share – both necessitate a lower feed-in tariff (FiT) while balancing the burden on the exchequer. In such cases, the opportunity cost of selling power becomes higher for the farmer, as they could benefit more by growing more crops or selling water to neighbours. We find that, in specific contexts, farmers have chosen such alternative options, which in turn affects the loan repayment and the financial viability of the model. We also found that the SERCs are not adequately equipped to assess the opportunity costs of selling surplus power while deciding the FiT, leading to a wide variation in the FiT under Component-C across states.

We also identify operational challenges for the discoms pertaining to metering and billing, free-ridership, and gaps in infrastructure. While metering is critical for accounting under Component-C, it is afflicted by issues of trust deficit between the farmers and the discoms and challenges in billing sparsely distributed agricultural connections. The free-rider problem emerges when only some farmers in a feeder participate in the scheme, while the rest gain access to reliable day-time supply without investing in the solar asset. Finally, inadequate maintenance of the agricultural feeders by the discoms due to poor revenue recovery is also a concern, as Component-C requires that feeders are well-maintained and on, at least during the daytime.

Overall, there remain significant uncertainties around the economic viability and operational sustainability of Component-C. We propose the following steps to address the unknowns before implementing the model at scale.

1. Discoms should lead the component’s implementation

The study makes it abundantly clear that the implementation of the component will throw up many challenges that only the discoms can tackle. The discoms’ role in Component-C is pre-eminent, and all the states should appoint the discoms as the implementing agency for the component.

2. Pilot the model in different contexts

The experience from the limited number of pilots on the individual-pump solarisation model so far suggests that the outcome of Component-C depends on an array of localised factors. The current cropping pattern, the existing power supply conditions and alternative options with surplus power are some of these determinants. Given that these factors vary immensely even within states, states must carry out pilots in different agroeconomic contexts before scaling up the model. The pilots should specifically test out the following aspects:

Beneficiary contribution and metering modalities: Farmer’s willingness to pay for solarisation would depend on many factors like the current supply condition, the FiT and the metering modality. The discoms need to test out different combinations of financing structure and metering options acceptable to farmers and assess their economic viability.

Use of surplus power and impact on groundwater: Using surplus power for selling water or cultivating more crops can put more stress on the groundwater, particularly in water-scarce regions. The discoms should conduct pilots to study farmers’ behaviour concerning surplus power and water use, to better plan their deployment strategy. They should also prioritise farmers using water-efficient practices to achieve the component objectives sustainably.

Feasible approaches to address metering, billing and free-rider problem: Technological solutions like smart meters and smart transformers can address some of the operational concerns but come with their own challenges. Network connectivity and trust issues with remote billing can pose a challenge. The discoms must engage with the farmers in the target feeder to ensure maximum participation in a feeder, build trust, and promote community ownership of the scheme during the pilots.

Infrastructure costs: The discoms should carry out comprehensive infrastructure assessment in the pilot projects to assess the infrastructure challenges and costs. The study should include pump sizes in use by the farmers, the status of grid infrastructure, and sources of other commercial losses before implementing the component in any feeder.

3. Complement the component with other key measures to make it viable

The states along with the MNRE could take some essential steps to make Component-C more feasible and sustainable.

Larger reforms in agriculture power supply: It is pretty difficult to get farmers to contribute to the scheme component in the backdrop of free agriculture power. Component-C cannot be decoupled from the larger reforms needed in the sector. Instead, it should be implemented in consonance with subsidy and tariff reform measures.

Pump replacement: Although the states are not receiving the central government’s subsidy share for pump replacement, replacing old inefficient pumps with efficient ones is likely to have a net positive outcome for both the state and the farmer. The discoms can test out the overall benefit from pump replacement through pilot studies.

Framework for determining FiT: As the conventional methods of determining electricity tariffs are inadequate to capture the complexities of the scheme, the MNRE should create a framework to guide the SERCs to determine a FiT that is viable for the discom, farmers, and the state government.

The PM-KUSUM scheme has been running since early 2019. However, the progress of the scheme, particularly on the two novel approaches that it introduced, components A and C, has been marginal, at best. These components intend to support farmers with additional incomes, improve power quality for irrigation, reduce agriculture power subsidies, and further clean-energy transition in the agriculture sector. However, the planning and implementation challenges at the state level are significant and need immediate attention to materially yield outcomes against these components of PM-KUSUM.

For Component-A, most of the discoms are enthusiastic. However, they are concerned about the short-term disruption in their finances. The concern stems from the fact that many discoms across the country already have surplus contracted capacity. With existing PPAs to honour, the room for additional procurement under Component-A is limited, even though it makes economic sense in the medium- to long-term. Modifying the scheme timelines and converging them with state-level power procurement planning would allow the discoms to leverage this model to meet future energy demand in a planned manner.

Further, the current ceiling tariffs finalised by many states are not finding traction among developers. Relatively higher capital and overhead costs for small-scale power plants, poorer grid availability at the distribution substation, and counterparty risks increase the cost of power under Component-A as compared to utility-scale solar plants. The MNRE must prepare a model framework, in consultation with the Forum of Regulators, to guide the SERCs in using a standardised approach in determining viable ceiling tariffs for projects under Component-A. The impact of recently introduced basic customs duty on solar modules and cells should also be assessed thoroughly as they disproportionately impact the capital cost of plants under Component-A.

Beyond the economics of the component for the discoms and the developers, the implementation challenges such as restrictions and delays in leasing or conversion of agricultural land and lack of interdepartmental coordination must be addressed on priority. A steering committee for PM-KUSUM consisting of representatives from all concerned state departments could go a long way in enabling smoother coordination for the scheme’s implementation.

Finally, farmers aiming to invest under Component-A are facing difficulties in accessing institutional finance. Innovative models such as farmer and developer SPVs can help unlock financing for farmers.

For Component-C, we focused on the grid-connected solar-pump model. Most discoms anticipate significant challenges in getting farmers’ buy-in for the model. In states with highly subsidised agricultural tariff, the discoms expect a lack of interest among farmers in making a monetary contribution to solarise their connection. We found that the model is economically viable for farmers, the discoms and the government only in very specific contexts. Low FiTs means limited incentives for farmers to feed surplus power back to the grid, while a high tariff would mean a net loss for the government/discoms. Current experiences at the state level suggest a cautious way forward: careful design of the scheme financing model, limited pilot roll-outs under different agroeconomic contexts, observation of farmers’ behaviour in the initial years, and finally scaling up the model only in suitable contexts.

For farmers, there could be high opportunity costs associated with the export of power. In certain scenarios, farmers may prefer to sell water or grow more crops instead of exporting surplus power, which can put pressure on groundwater in water-stressed areas . We propose that the SERCs be aware of these factors while determining the FiT for the scheme. Similar to our suggestion for Component-A, the MNRE should prepare a framework to guide SERCs in determining viable FiT for Component-C.

Beyond economic viability, operational challenges related to metering and billing, the non-participating farmers in a feeder, and the poor state of agriculture distribution infrastructure are worth noting. Employing technologies like smart devices in conjunction with community-engagement efforts can help the discoms bridge the trust deficit with farmers. Alongside, comprehensive feeder-level assessments are imperative to address infrastructure gaps.

Having said that, unless measures are taken to reform the larger issues of agriculture power subsidy and its administration, the individual solarisation of agricultural pumps may not fly with the discoms and farmers at large. While the government should address the challenges we outline to fast track implementation of PM-KUSUM, it must not lose sight of the fact that a perfect solution in an imperfect environment may not succeed.

Tamil Nadu’s Greenhouse Gas Inventory and Pathways for Net-Zero Transition

The Emissions Divide: Inequity Across Countries and Income Classes

Implications of an Emissions Trading Scheme for India’s Net-zero Strategy

Demystifying Carbon Emission Trading System through Simulation Workshops in India