Suggested Citation: Harihar, Nandini and Ankur Malyan. 2024. Rethinking Ocean Governance in an Era of Climate Urgency: Science, Impact and the Complexities in Between. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

The governance of the ocean is not a novel concept; however, like climate change and energy, its transboundary nature and the involvement of several stakeholders complicate it. This inherent diversity of interests leads to regime complexities and challenges in developing comprehensive regulatory systems. While various laws and treaties ensure peaceful, cooperative, and legally permissible use of the seas and the ocean, these efforts have so far been insufficient and fragmented, resulting in uncoordinated action, limited monitoring and enforcement, and over-exploitation of marine resources. It is, therefore, crucial to advocate for a suitable governance framework and institutional coherence along with science- and technology-driven initiatives to effectively respond to the growing pressures on the ocean.

This report is divided into three thematic sections: Science, Impact, and Governance. Section 1 highlights the effect of anthropogenic emissions on ocean warming, acidification, and ocean carbon storage capacity. Section 2 discusses the impact of climate change on the jobs and growth in blue economy sectors and the sustenance of coastal communities. Section 3 examines the regime complex in ocean governance by analysing 62 marine agreements and conventions at the global (19) and regional (43) levels and the supporting governance arrangement of 45 marine institutions to drive collaborative action.

The ocean is the largest carbon sink in the world with a capacity of 38,100 GtC – 16 times greater than soil and vegetation (2,410 GtC) and 50 times more than the atmosphere (760 GtC) (Sallée 2018). It also drives fundamental geoscience mechanisms critical for the survival of life on Earth. This includes absorbing over 90 per cent of the additional heat generated due to greenhouse gases, producing over half the world’s oxygen, and redistributing heat across the globe to regulate climate and weather patterns. The ocean provides income and employment to millions and fulfils the nutritional needs of nearly three billion people globally. The marine fisheries sector supports 200 million livelihoods – equal to the combined population of France, Germany, and Spain (as of 2023). By 2030, it is estimated that the global value added by the ocean economy will peak at USD 3 trillion, providing 40 million full-time equivalent jobs (OECD 2016). However, the overall ocean asset value (natural capital) is far greater, amounting to USD 24 trillion (Commonwealth Secretariat 2022; ADB 2021).

Nevertheless, these global benefits of the ocean are mired with challenges, such as climate change, ocean warming, sea-level rise, ocean acidification, and ineffective management of resources. These challenges alter marine productivity and ecosystem services, constrain the availability of resources, limit economic growth and development opportunities, and adversely impact the lives, livelihoods, and sustenance of dependent communities. Rising sea surface temperature (SST) due to climate change will likely alter global wind and weather patterns, affecting food and water security. For instance, in the past two decades, the frequency of tropical cyclones in the Arabian Sea has increased in comparison to the Bay of Bengal. Similarly, land inundation due to sea-level rise and climate migration is already a reality in some low-lying island states. Furthermore, the dual impact of climate change and ineffective fisheries management will likely decrease catch potential globally by 2050 (FAO 2018c). This will have severe consequences for jobs in developing countries, which account for 97 per cent of the world’s fisher workforce, economic growth in countries where the fisheries sector contributes significantly to the national GDP, and sustenance of coastal communities by adversely affecting livelihood opportunities and food security. Finally, the lack of blue finance is a critical concern. Even though a third of all Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) targets depend on ocean sustainability, SDG 14 is one of the least funded by official development assistance (ODA) providers (Singh et al. 2018; OECD 2020).

Despite our critical dependence on the ocean and its resources, the overall governance of the ocean is limited. Like climate change, energy security, and trade, the challenges of the ocean go beyond national borders. The transboundary nature of the ocean and the involvement of several stakeholders complicate the effective governance and management of this shared resource pool. The inherent diversity of interests leads to a regime complex, which challenges the development of comprehensive regulatory systems (Folami 2017; Keohane and Victor 2010). The current ocean governance structure is loosely linked, resulting in overlapping interests amongst diverse stakeholders. The ongoing challenge is to overcome this fragmented landscape of ocean governance, which is long-term and cannot be solved by a single nation. This is the crucial catalyst for discussing global ocean governance.

Ocean governance must be designed and implemented in an integrated manner involving all relevant stakeholders to enhance biodiversity protection, build the adaptive capacity of marine ecosystems and coastal communities, improve ocean stewardship and management of its resources, drive overall societal development, and shield vulnerable communities from climate change impacts. As of November 2021, only 54 NDC submissions from coastal states include at least one ocean-based action (Carbon Market Institute 2021). These must go beyond announcements to deliver action. In this regard, it is critical to explore the ocean’s existing institutional and governance landscape to identify gaps and loopholes rather than create additional institutions that carry forward legacy issues in management.

This report explores three research questions:

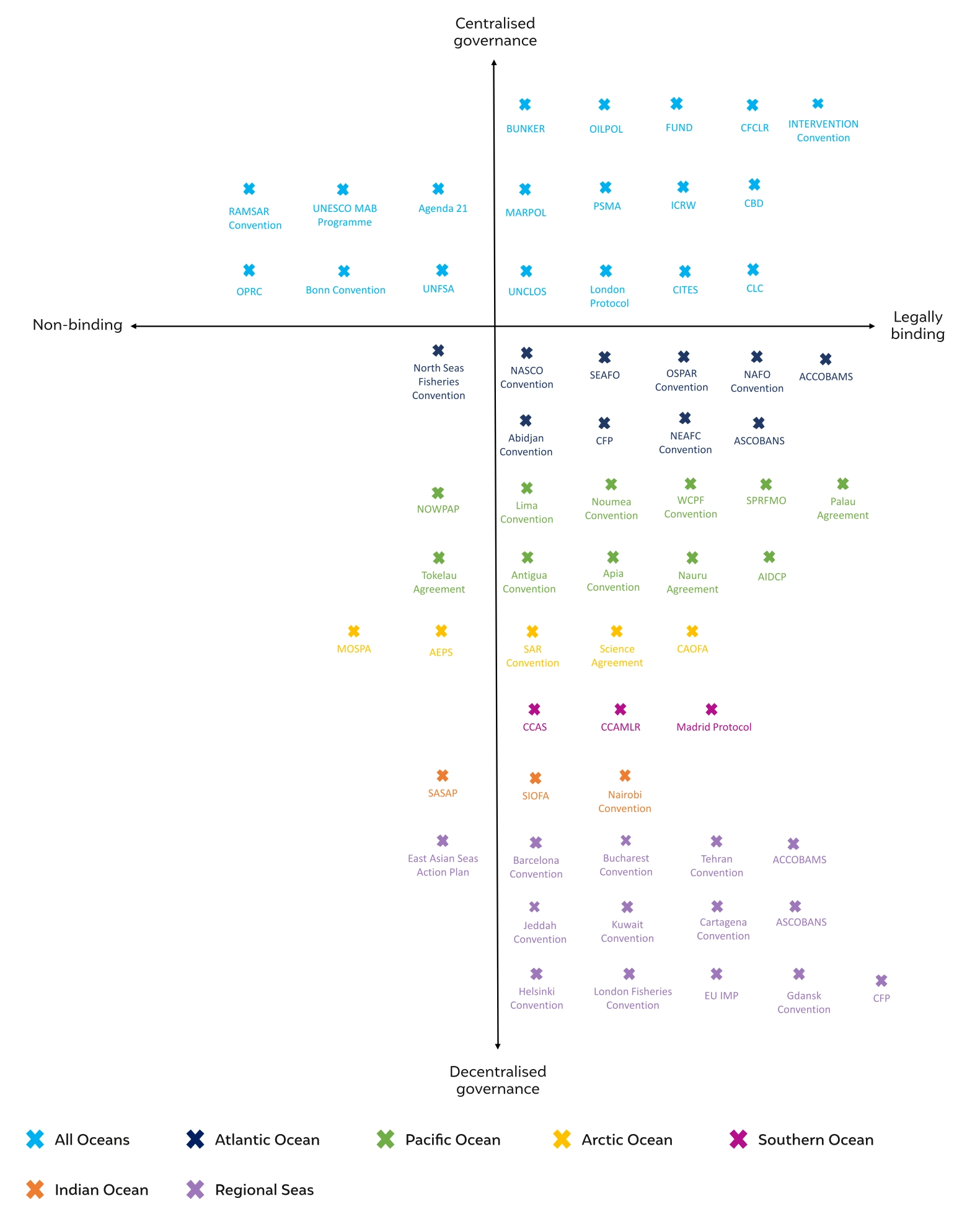

The study analyses 62 global and regional agreements and conventions to highlight three aspects of regime complex in ocean governance: a) regulatory, b) regional, and c) issue-based.

Global and regional agreements and conventions are skewed in their focus and coverage

Figure ES1 illustrates the regulatory aspect of ocean governance. The horizontal axis represents functionality, i.e., the regulatory nature of marine agreements and conventions (legally binding or non-binding). The vertical axis highlights the spatial dimension, where ‘centralised’ implies governance in international waters, and ‘decentralised’ means focusing on a specific sea or ocean. The analysis highlights that 13 out of 62 agreements and conventions are centralised, with nearly 70 per cent established in a decentralised manner. Furthermore, 46 out of 62 marine agreements and conventions are decentralised and legally binding. Nearly 84 per cent of all agreements and conventions are legally binding, while centralised and non-binding account for a little less than 10 per cent of the portfolio. Given that 64 per cent of the ocean’s surface lies in marine areas beyond national jurisdictions (ABNJ) – commonly referred to as the high seas or international waters – regional (decentralised) agreements are insufficient. Centralised agreements such as UNCLOS, MARPOL, PSMA, and CLC are critical to laying the governance framework on the high seas on which regional and national policies can build.

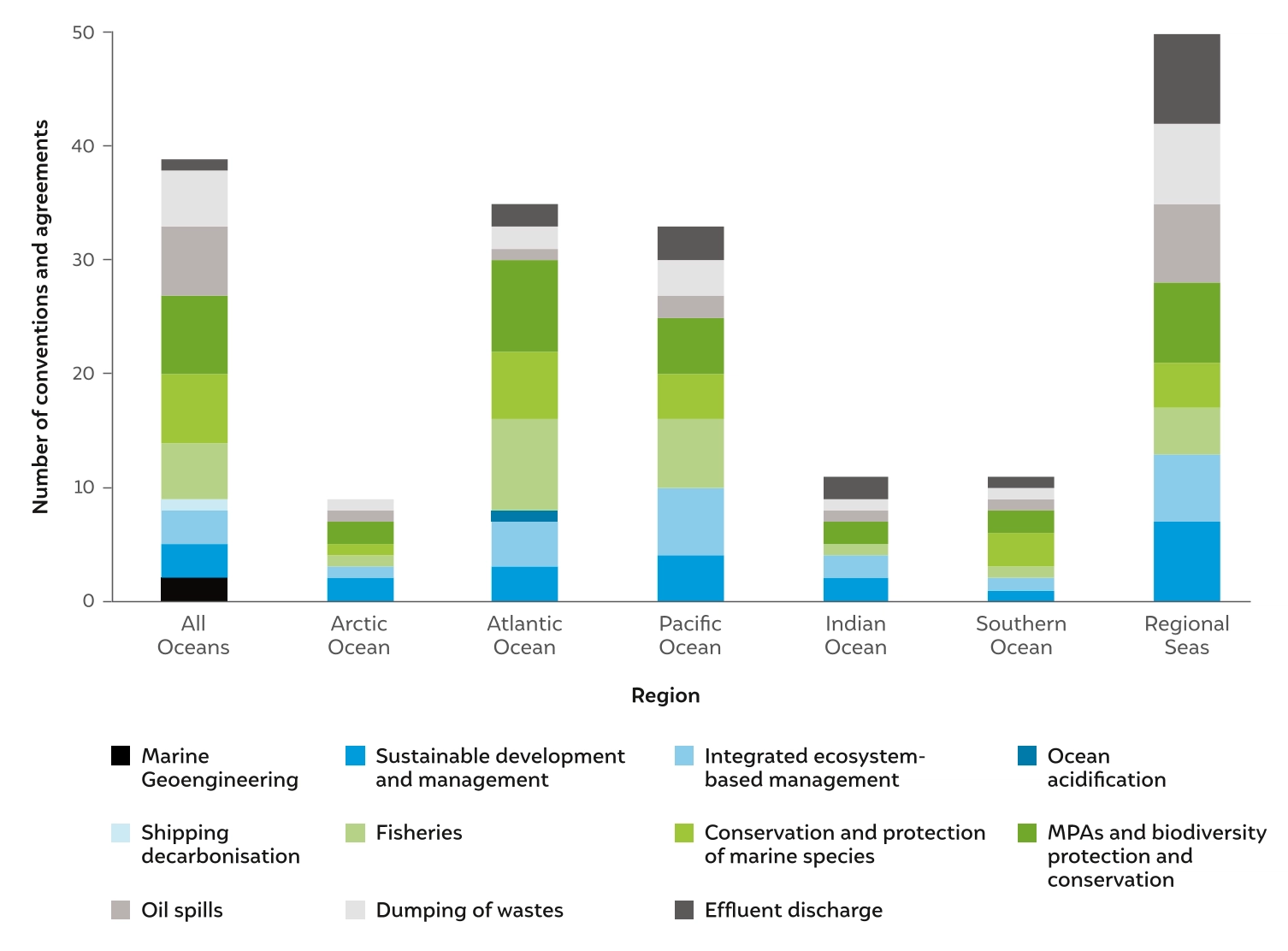

Secondly, marine issues receive varying attention regionally, depending on the ocean basin, the surrounding nations, and the strength of their economies. In the Atlantic Ocean, most agreements and conventions focus on marine protected areas (MPAs) and biodiversity protection, fisheries, and the conservation and protection of marine species. Fewer agreements and conventions govern the Indian Ocean with emphasis on integrated ecosystem-based management (EBM), sustainable development and management, MPAs and biodiversity protection, and effluent discharge (Figure ES2).

Thirdly, from an issue-based perspective, most marine agreements and conventions focus on MPAs and biodiversity protection (56 per cent), fisheries management (42 per cent), and integrated EBM (41 per cent). In contrast, issues such as marine geoengineering and reduction in greenhouse gas emissions receive little attention, with only a few regulations under the Convention on Biological Diversity and London Convention/London Protocol and MARPOL, respectively.

This inherent regime complex in ocean governance has resulted in unplanned and uncoordinated action towards ocean resource management, overexploitation of marine resources, lack of compliance, poor implementation, limited monitoring and enforcement, and unclear ownership of and responsibility for the high seas.

Effective institutional collaboration can address some complexities in the governance of the high seas

We evaluate 45 marine institutions (international, regional, and intergovernmental and UN organisations; academia and scientific institutions; private-sector and civil society organisations) (Annexure 3) to highlight the overlaps across different functionalities. These include scientific research, policy research, conservation, management and regulation, advocacy, and knowledge mobilisation and building business strategies and partnerships.

Figure ES1 The regulatory landscape of ocean governance

Source: Authors’ analysis

The analysis highlights that nearly 59 per cent of these institutions are involved in conservation, management, and regulatory functions; 48 per cent work in scientific research; and 45 per cent work in knowledge mobilisation and building business strategies and partnerships (Figure 4).

Nearly a fourth of these institutions focus only on a specific function, while 39 per cent and 30 per cent are bi-functional and tri-functional respectively (Annexure 3). We also find that out of 45 institutions, 14 focus on policy research. Of this, only five institutions – Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), International Union of Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), and United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) – work parallelly on scientific analysis alongside policy to bridge the science-policy interface gap; this is critical to developing evidence-based solutions.

The study finds that the design and cross-functioning of institutions are critical in addressing complexities in managing the marine environment. For instance, the management approach of the CCAMLR’ set a precedent for more MPAs to be developed in international waters. Secondly, in 2020, the NEAFC adopted new conservation and management measures for fish stocks based on scientific advice and in collaboration with the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) (NEAFC 2020). Finally, the co-adoption of the Collective Arrangement by OSPAR and NEAFC helped manage human activities in the ABNJ. Hence, coherence and coordination across institutions, conventions, and commissions is critical to break out of silos, address varying marine challenges, and drive more collaborative efforts towards the sustainable management of the ocean and its resources.

Figure ES2 Regional issue-based classification of ocean agreements and conventions

Source: Authors’ analysis

While collaborative efforts sound rational, achieving them on a global or even regional scale in the ocean is difficult due to the regime complex of this shared resource pool. We propose the following recommendations to improve ocean governance:

The biggest wave to surf is the lack of political will and commitment towards ocean action; without finance, commitments cannot be delivered. A critical outcome of COP29 must be to procure blue finance at scale for SDG 14. For this, new avenues of blue financing need to be explored, and the narrow focus of climate finance must incorporate blue economy-related risks. Investing in the recovery and protection of the ocean ecosystems and better valuing and managing its resources can rebuild the ocean’s resilience and that of communities dependent on it.

Finally, establishing the pace of transition is critical to address climate and ocean action holistically. Success stories from CCAMLR, Helsinki Convention, Nauru Agreement, OSPAR Convention, and WCPFC and RFMOs capture the essence of national, regional, and global cooperation, data sharing and management, institution building, and the science-policy interface between marine economic sectors and industries. With the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development or the ‘Ocean Decade’, we hope that actions to build a sustainable ocean economy will accelerate in the coming decade.

The ocean enables fundamental geoscience mechanisms critical for the survival of life on Earth, including producing over half of the world's oxygen, absorbing nearly 50 times more carbon dioxide than the atmosphere, storing over half of the global carbon reserves in the deep ocean, and redistributing heat across the globe to regulate the climate and weather patterns (Fleming, 2019; Bates 2019; Bigg et al. 2003). The ocean also provides income and employment to millions and fulfils the nutritional needs of nearly three billion people globally. By 2030, it is estimated that the global value added by the ocean economy will peak at USD 3 trillion, providing 40 million full-time equivalent jobs (OECD 2016).

The ocean is the largest carbon sink in the world, with a capacity of 38,100 GtC, almost 16 times greater than soil and vegetation (2,410 GtC) and 50 times more than the atmosphere (760 GtC) (Sallée 2018). This involves physical, chemical and biological processes to absorb CO2 from the atmosphere and store it in the deep oceans. The most abundant form is dissolved inorganic carbon, which enters the ocean through seawater interacting with sediments, land weathering, and gas exchange with the atmosphere. The biological carbon pump in the ocean's surface layers is another way to store carbon in the ocean. The phytoplankton convert the CO2 from the atmosphere and the dissolved CO2 in seawater into biomass through photosynthesis, a part of which sinks to the bottom of the ocean. However, studies suggest that ocean warming will increase the temperature gradient between the surface water and lower layers, reducing vertical mixing and resulting in greater stratification. This will negatively affect CO2 solubility in surface water. Without ocean CO2 uptake, current atmospheric CO2 concentrations would have risen to well over 450 ppm, driving far more adverse climatic impacts than those witnessed today (Quéré et al. 2015; Doney et al. 2009; Sabine and Feely 2007).

International environmental governance requires societal transformations of all economic actors and negotiations among various interested parties and stakeholders (Najam, Christopoulou, and Moomaw 2004). In the context of the ocean, this inclusive form of planning is described as ‘integrated ocean governance’, where different marine sectors and stakeholders aim to maximise their benefits while minimising their adverse environmental impacts (FAO 2016).

The current ocean governance framework is loosely linked, resulting in overlapping interests among different groups, unplanned and uncoordinated management, lack of compliance, poor implementation, and limited monitoring and enforcement. Some significant challenges include lack of information, unclear ownership and responsibility of the high seas, overexploitation of marine resources, and absence of adequate adaptation and management mechanisms to protect marine resources in a changing world. This is fuelled by unsustainable human activities driven by the growing demand for energy, food, trade, transportation, and recreation and made worse by climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution.

Trust and Transparency in Climate Action

Operationalising the Loss and Damage Fund to Address Climate Impacts

Sustainability-driven Non-tariff Measures

Jobs, Growth, and SustainabilityThe Case for a G20 Task Force on Integrated Climate Actions