Suggested Citation: Van Deursen, Max and Sumit Prasad. 2023. Trust and Transparency in Climate Action: Revealing Developed Countries’ Emission Trajectories. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

This issue brief aims to shed light on the mitigation performance of developed countries, drawing on developed countries’ self-disclosed information in official climate transparency reports. Based on this information, the study assesses past performance, as well as ambition of- and progress towards the implementation of key climate targets.

The study highlights that climate transparency reports contain powerful information, which can shed light on climate (in)action of developed countries. But whether transparency will foster trust ultimately depends on whether developed countries walk the talk and implement ambitious climate action.

What remains of the global carbon budget – a benchmark to keeping global warming below 1.5°C – is estimated to be about 500 GtCO2. This amount will be depleted by the end of the decade at the current rate of global emissions (IPCC, 2021). Given this limited carbon space, deep emission reductions are imperative in this critical decade (2020–2030). However, are developed countries, who are responsible for over 75 per cent of historical emissions (Busch, 2015), taking deep emission reductions at an adequate pace?

The mitigation efforts of developed countries have direct implications for the limited carbon budget available to developing countries, which need sufficient carbon space to address their economic and social development challenges and eradicate poverty. But surprisingly, there is little clarity on how developed countries are performing in relation to their commitments and the remaining carbon budget. In this issue brief, we aim to bridge this gap by analysing the emission trajectories of developed countries, covering historic and projected emissions in the six decades spanning 1990–2050. For this assessment, we used datasets officially disclosed by developed countries in their reports as submitted under United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) transparency arrangements.

We observed that, in the period 1990–2020, developed countries cumulatively emitted about 555 GtCO2e and reduced emissions by 20 per cent. While this is in line with the overall goal (18 per cent) of the Doha Amendment, it is important to note that a substantial part of this reduction can be ascribed to the COVID-19 lockdown in 2020 as well as emission reduction in the mid-1990s, when former Soviet countries made the transition to becoming market economies.

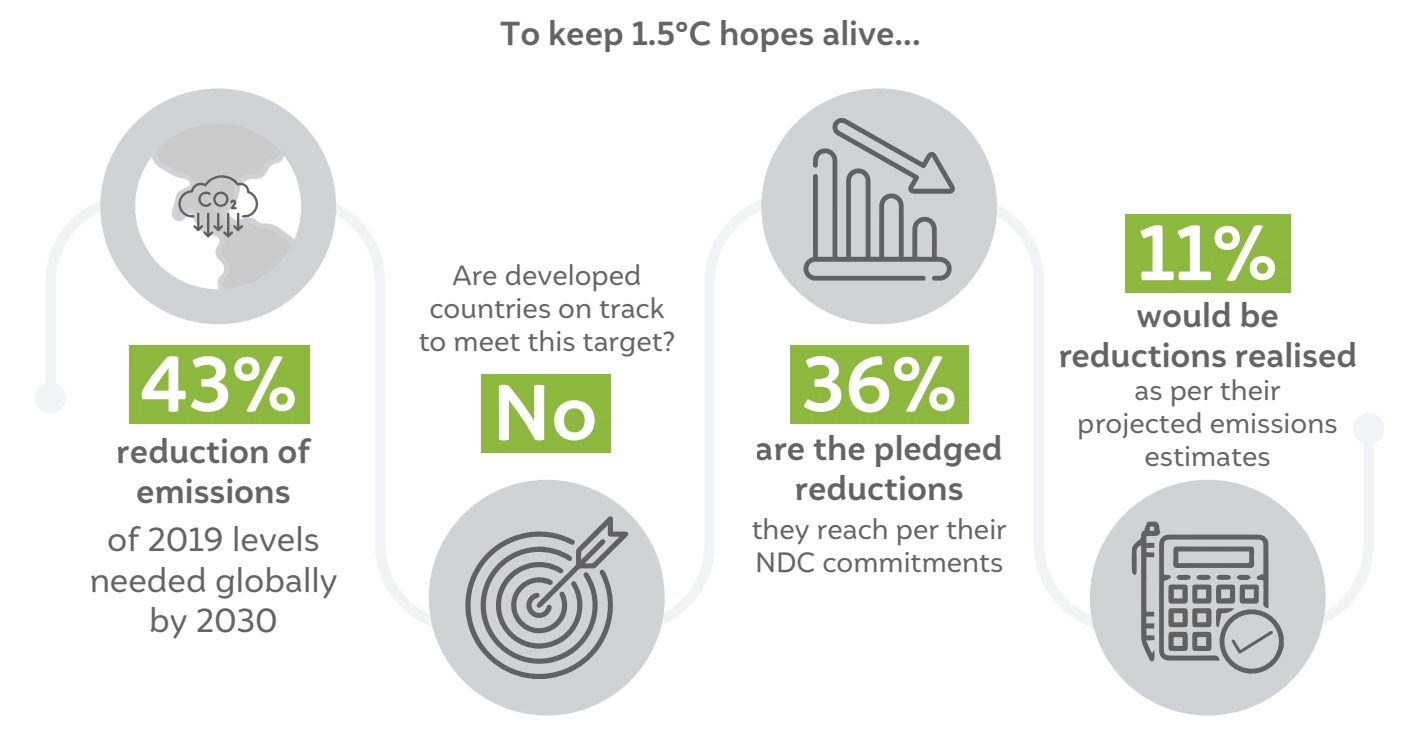

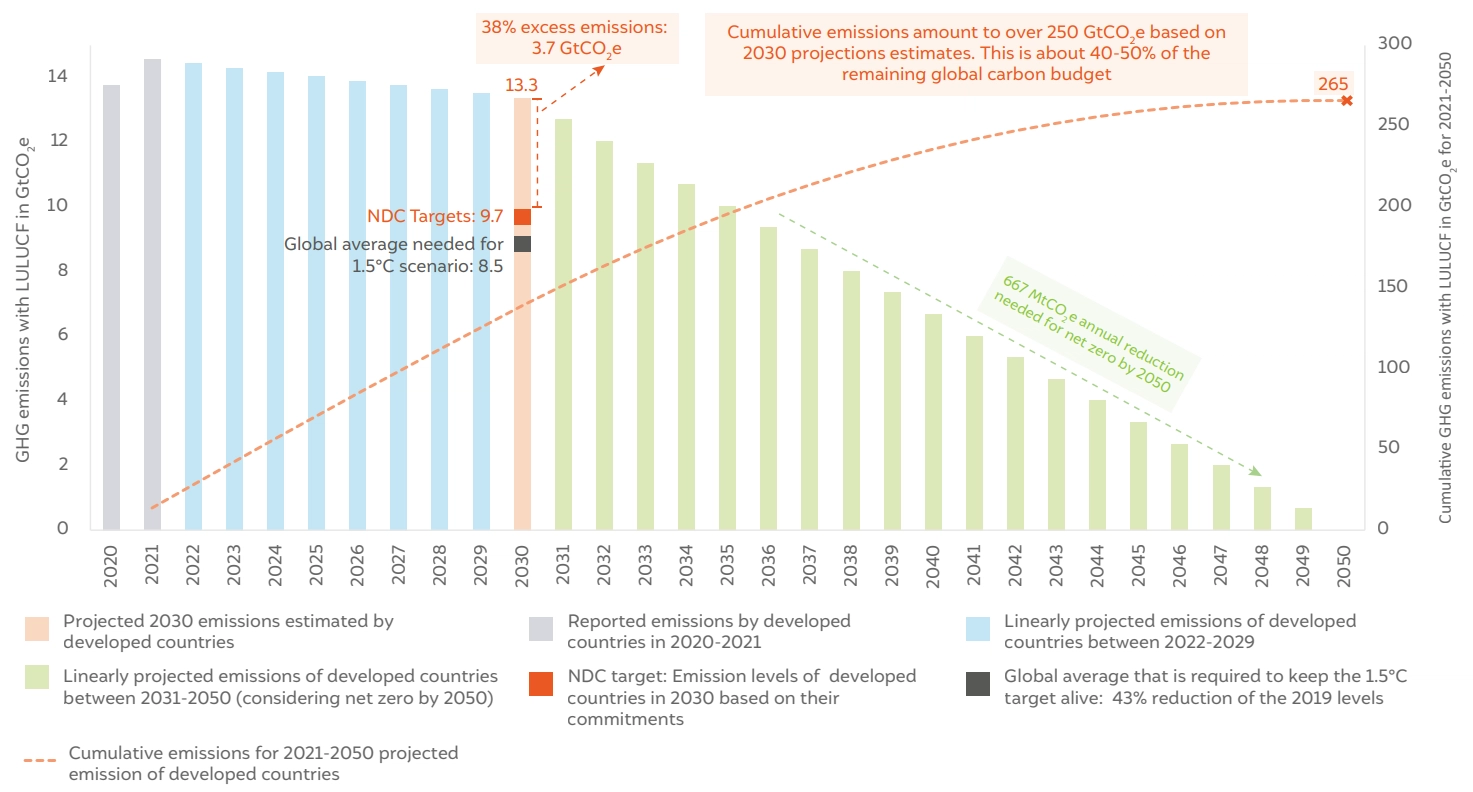

In terms of nationally determined contribution (NDC) targets for 2030, only two developed countries, namely Norway and Belarus, are on track to achieve their commitments. Developed countries are projected to collectively emit around 3.7 GtCO2e more in 2030 than the reduction goals they expressed in their NDCs. This represents a 38 per cent emission overshoot, and the United States, Russia, and the EU are responsible for 83 per cent of this overshoot. Further, collectively, NDCs of developed countries also fall short of the global average reduction levels – 43 per cent of the 2019 levels – needed to keep the 1.5°C target alive. The NDC targets represent a 36 per cent reduction of the 2019 levels while their projected 2030 emissions amount to only 11 per cent.

Source: Authors’ analysis

The projections also reveal that developed countries rely on drastically ramping up emission reductions after 2030 to meet their net-zero targets by 2050 rather than doing so before 2030. To achieve net zero by 2050 from the projected 2030 emission levels, these countries need average year-on-year reductions of 667 MtCO2e. This is more than four times the average year-on-year reductions in the period 1990-2020.

This delayed acceleration has implications for the carbon budget consumed by developed countries. We estimate that even if developed countries achieve net zero by 2050, they would collectively emit over 40 to 50 per cent of the remaining global carbon budget for the 1.5°C target, even though they are home to less than a fifth of the world’s population.

The climate journey of the developed countries has failed to produce deep emission cuts; this is not projected to change by 2030 and jeopardises any chances of achieving the 1.5°C target. We present five recommendations to course-correct:

Climate change has already led to a 1.1°C rise in temperature (IPCC, 2021). This has resulted in changes in weather patterns and climate extremes in every region across the globe (IPCC, 2021). The loss and damage related to climate change has already cost the V20, a group of vulnerable countries, 20 per cent of their GDP in the last two decades (V20, 2022). Loss and damage could cost developing countries USD 290–580 billion by 2030 and USD 1.3–1.7 trillion by 2050 (Markandya & González-Eguino, 2019). Future climate-induced economic damages per capita are estimated to be higher for developing countries than for developed countries (IPCC, 2022a). With every increment of warming, this number is expected to increase exponentially (IPCC, 2022a).

To avert the worst impacts of climate change and limit global warming to 1.5°C, global greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) need to be reduced by 43 per cent of their 2019 levels and global carbon dioxide emissions need to reach net zero by 2050 (IPCC, 2022b). However, the climate targets under the Paris Agreement are insufficient to limit global warming to under 1.5°C (UNFCCC 2022; IPCC, 2022b). In an attempt to turn the tide, the 2021 Glasgow Climate Pact stressed “the urgency of enhancing ambition and action […] in this critical decade” and further established a “work programme to urgently scale up mitigation ambition and implementation in this critical decade” (UNFCCC, 2021). These calls for acceleration notwithstanding, progress in ramping up ambition has been limited (UNEP, 2022; UNFCCC, 2022).

Although the developed countries have left an oversized carbon footprint, climate change will hit developing countries hardest. During the period 1850–2019, North America, Europe, Australia, Japan, and New Zealand – which collectively represent less than 15 per cent of the world’s population – were responsible for 55 per cent of historical emissions. By comparison, Africa, home to 17 per cent of the global population, is responsible for less than 3 per cent of historic emissions (Dhakal et al. 2022). Per capita emissions are also strikingly unequal across regions. For example, the average person in Africa and South Asia emits 1.2 and 1.6 tonnes of carbon dioxide every year respectively; meanwhile, per-capita emissions stand at 16 tonnes for North America and 6.5 tonnes for Europe (IPCC, 2022b).

This disparity was even higher in 1992, when the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was adopted. Consequently, the 1992 Climate Convention adopted the core principle that developed countries should take the lead in reducing emissions. Their leadership was seen as particularly important, as the convention anticipated that developing countries would increase energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions in the process of poverty reduction, development, and industrialisation.

The mitigation performance of developed countries has direct consequences for the carbon budget available to developing countries. At the beginning of 2020, the carbon budget available to limit warming to 1.5°C was estimated to be 500 GtCO2 – an amount that will be depleted by the end of the decade at the current rate of global emissions (IPCC, 2021). Despite this very low carbon budget, there is surprisingly little clarity on what share developed countries will use, partly because point-year reductions and net-zero targets say little about emission trajectories.

Transparency arrangements under the UNFCCC mandate the disclosure of important information on developed countries’ emission trajectories. However, this requirement does not necessarily translate into accountability (Gupta & van Asselt, 2019). Moreover, related reports are so voluminous and detailed that their findings seldom receive due attention in mainstream media and policy processes.

The purpose of this issue brief is to assess the mitigation performance of developed countries. We cover historic and projected emissions for the six decades spanning 1990–2050. This assessment is of key importance to developing countries. The greenhouse gas emission trajectories of developed countries have direct consequences for the global carbon budget, and by implication, the carbon space available to developing countries.

To assess the emission trajectories of developed countries, we use countries’ self-reported information on historic greenhouse gas emissions and projections, as disclosed in UNFCCC transparency arrangements. The projections are most likely estimates of developed countries future emissions for 2030, which these developed countries are mandated to report on a biennial basis. All data is publicly available on the UNFCCC website. A supplementary Excel spreadsheet, which covers the data points and tables we discuss in this brief, is also available on our website.

In Section 2, we cover developed countries’ emission trajectories from 1990–2020. By looking retrospectively at emissions in this period, we aim to shed light on the extent to which developed countries have managed to reduce emissions. Section 3 scrutinises emission trajectories in the current critical decade and highlights the progress of developed countries towards their 2030 targets. Section 4 assesses the implications of the projected emissions reaching net zero by 2050. Section 5 concludes with our recommendations based on our findings.

The implementation of pre-2020 commitments was of utmost importance to achieve the overall objectives of the UNFCCC. Under the Kyoto Protocol and its Doha Amendment, developed countries were obligated to lead global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions; they had legally binding targets. Collectively, developed countries were to reduce emissions against their 1990 levels by 5 per cent in 2008–2012 and by 18 per cent during 2013–2020.

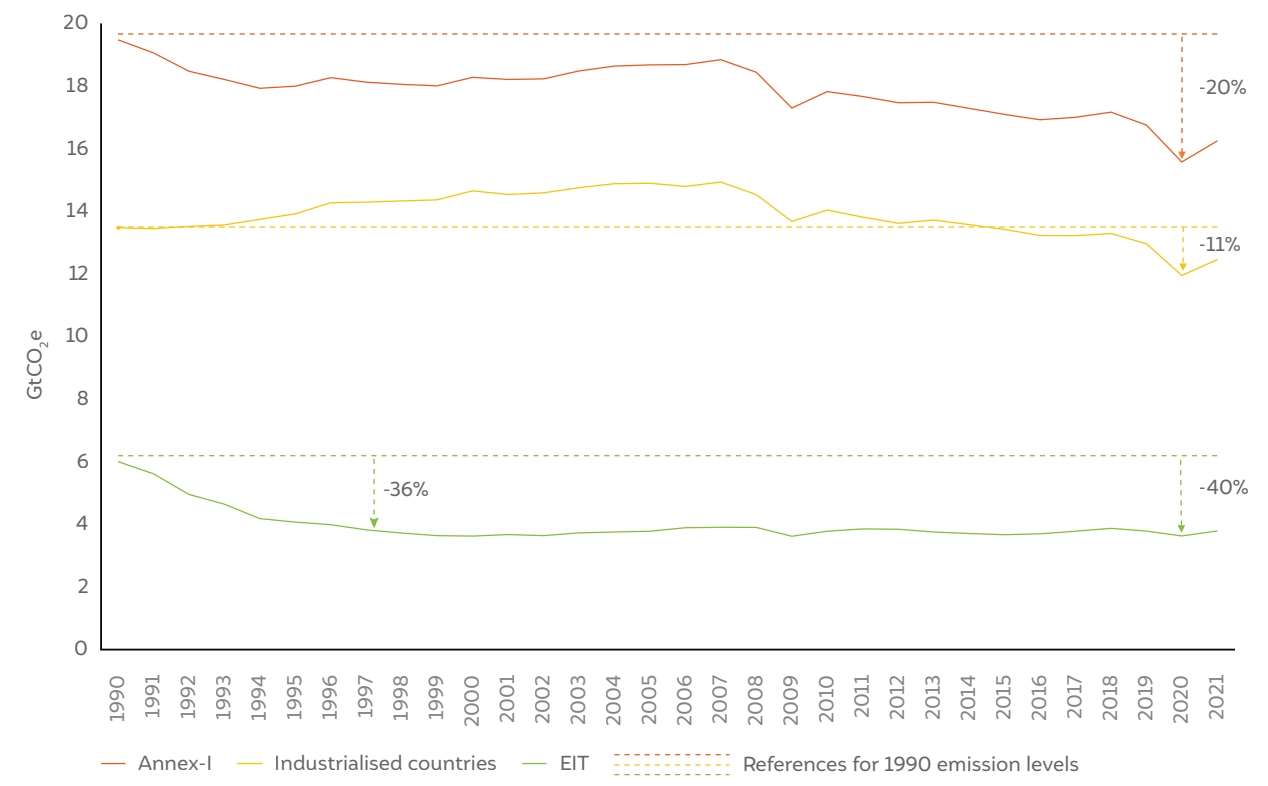

Figure 1 Greenhouse gas emissions of developed countries (1990–2021)

Source: Authors’ analysis

Note 1: The emission trajectories show in this graph are without emissions from Land Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF).

By 2020, developed countries had collectively reduced emissions by 20 per cent compared to their 1990 levels. While this indicates that developed countries are in line with the overall goal of the Doha Amendment, it is difficult to relate this achievement with planned emission reduction measures. As Figure 1 shows, the majority of the emission reductions in developed countries during the pre-2020 period was driven by economies in transition (EIT). These economies witnessed a significant emission reduction – a reduction of 36 per cent by 1997 compared to 1990 – well before the start of the Kyoto Protocol/Doha Amendment. This reduction was due to their transition from centrally planned to market-based economies and not because of planned emission reduction measures (CEEW, 2021). Secondly, there was a significant drop in emission levels in 2020 as a result of the global economic slowdown because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The pre-2020 climate regime also witnessed several challenges as a result of the non-participation of many major developed economies in the climate agreement, inflated base year emissions, and accounting loopholes (CEEW, 2021).

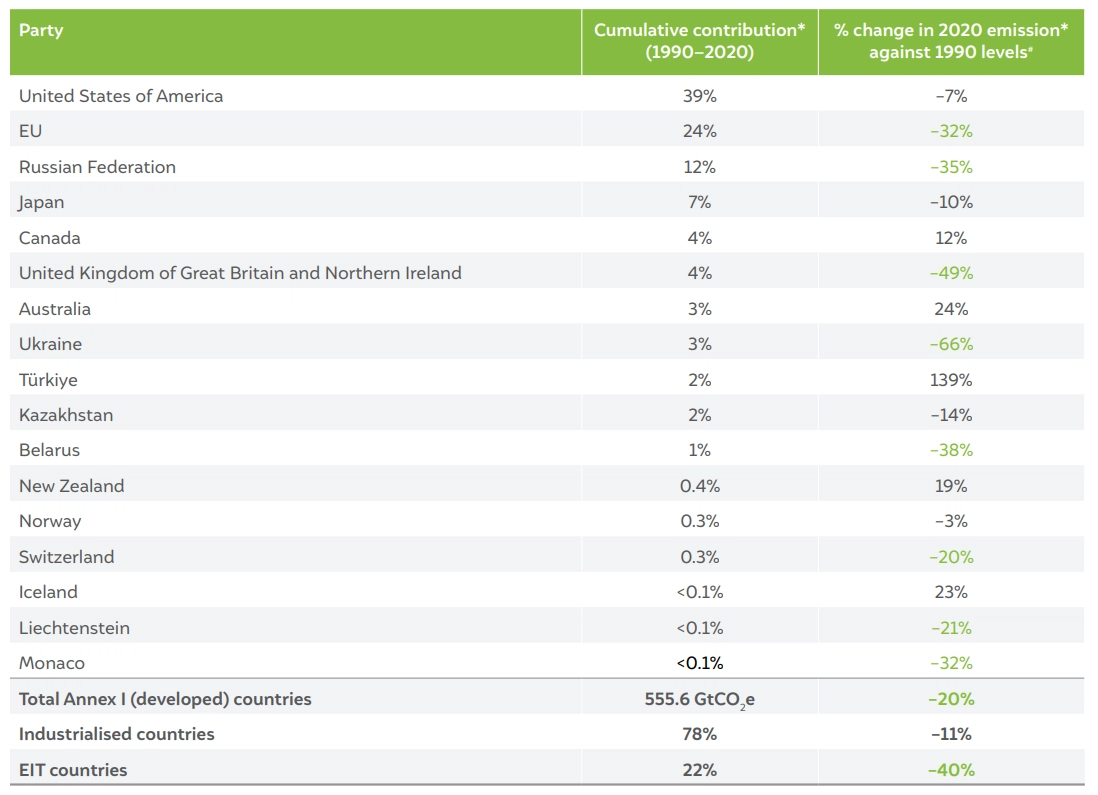

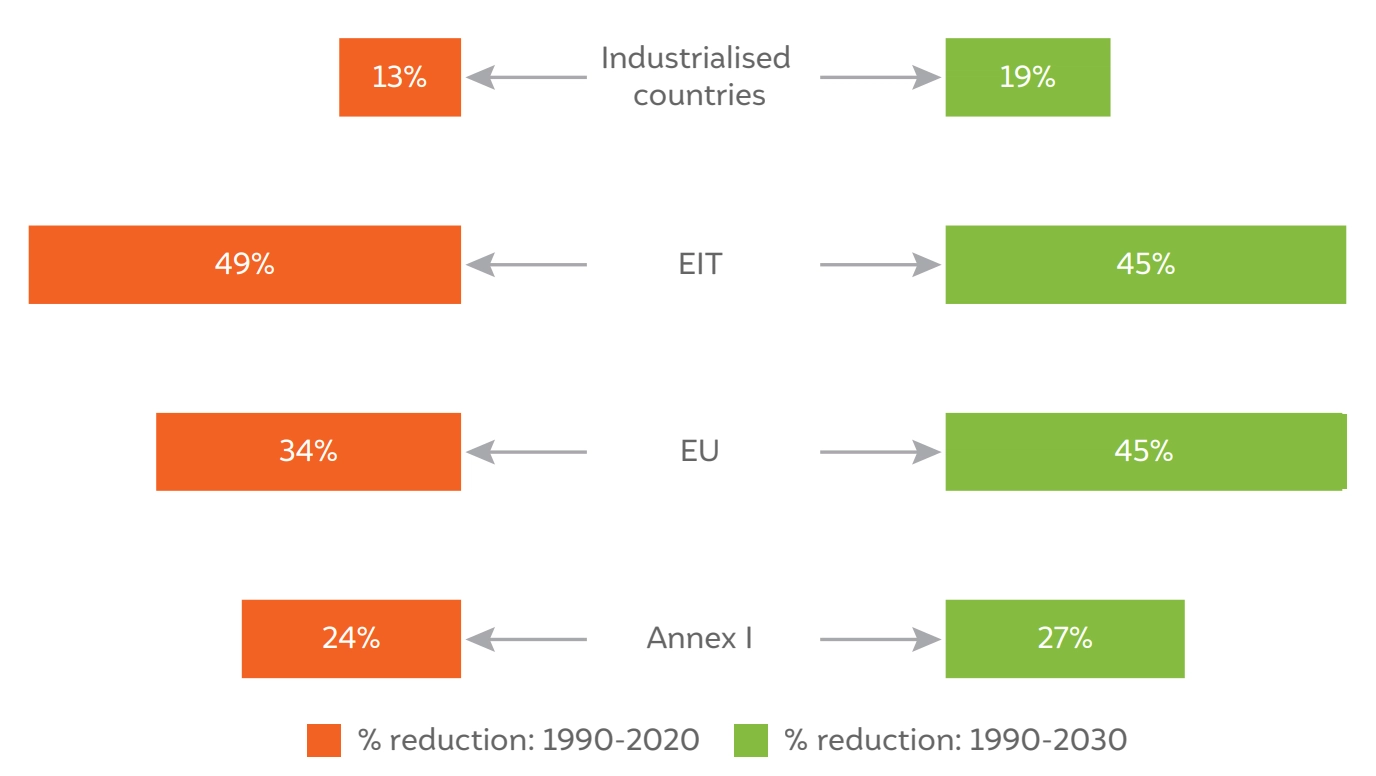

Table 1 Uneven progress in emission reduction among developed countries (1990-2020)

Source: Authors’ analysis

Table 1 highlights the Parties’ 2020 emission changes against their 1990 levels as well as their contribution to the cumulative emissions by developed countries during the period 1990–2020. We then benchmark (in green) these reductions with the overall emission reduction goal of the Doha Amendment but do not assess the actual compliance of the Parties against their individual targets.

Based on this analysis, we observed that, during the three decades of the pre-2020 regime, developed countries collectively emitted about 555.6 GtCO2e. Four Parties – the United States of America, the European Union, the Russian Federation, and Japan – account for more than 80 per cent of this cumulative emissions of developed countries in 1990–2020. While the EU and the Russian Federation have achieved reductions beyond the Doha Amendment’s overall goal of 18 per cent reduction, the United States of America (the highest contributor) and Japan are not close to this goal.

We also observed that significant reductions on the part of the United Kingdom, Ukraine, Belarus, and Switzerland have exceeded the overall goal. But for several other Parties, namely, Canada, Australia, Türkiye, New Zealand, and Iceland, we observed an increase in emissions instead of a reduction – despite the global lockdown resulting from COVID-19 in 2020 – from their 1990 levels.

The Paris Agreement urges developed countries to commit to economy-wide emission reduction targets. In line with this, these countries communicated new or updated NDCs to be achieved by 2030. It is crucial to scrutinise their progress towards 2030 targets, as the current decade is pivotal in limiting global warming to 1.5°C.

To keep the 1.5°C target alive, by 2030, global emissions should be reduced to 43 per cent from their 2019 levels. Are developed countries’ NDC targets aligned with this global average? Figure 2 shows that the NDC targets as well as the projected emissions of developed countries are well below the required global average reductions needed by 2030.

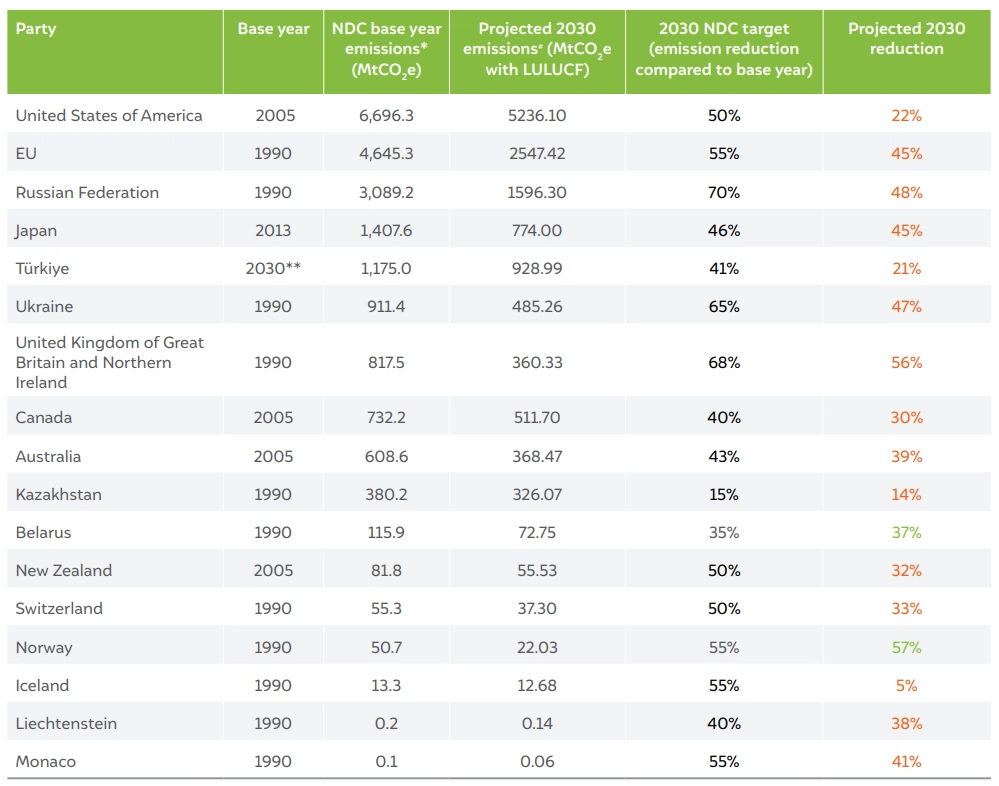

We must also ask: which developed countries are on track to meet their NDCs? A UNFCCC synthesis report compiles the self-submitted emission projections of developed countries. It narrates a crucial message: none of the developed countries are projected to meet their 2030 climate targets (UNFCCC, 2023). The UNFCCC’s synthesis report draws on information submitted in developed countries’ fourth Biennial Reports. Table 2, which is based on their latest submissions, provides an updated estimate, drawing on the fifth Biennial Reports. It compares developed countries’ NDC targets with their self-reported projected emissions.

Figure 2 Developed countries’ 2030 targets and projected emissions do not meet the global average of reductions needed to keep the 1.5°C target alive

Source: IPCC 2022b, Authors’ analysis

Table 2 Most developed countries are projected to miss their 2030 NDC targets

Source: Authors’ analysis

Note: The green-highlighted projected reductions for 2030 signify that the country is on track to achieve its 2030 NDC target, while the red-highlighted reductions indicate that the country is projected to fall short of its NDC target.

Table 2 shows that only two developed countries, namely Belarus and Norway, are on track to meet their 2030 NDC targets. But they account for less than one per cent of the total set of developed countries’ projected emissions in 2030. Two other developed countries – Japan and Kazakhstan – are projected to miss their 2030 NDC targets by only one percentage point.

Further, developed countries are projected to collectively emit around 3.7 GtCO2e more in 2030 than they pledged in their NDCs – more than the annual emissions of the EU at present – representing a collective 38 per cent emission overshoot. The United States, Russia, and the EU are responsible for 83 per cent of this overshoot.

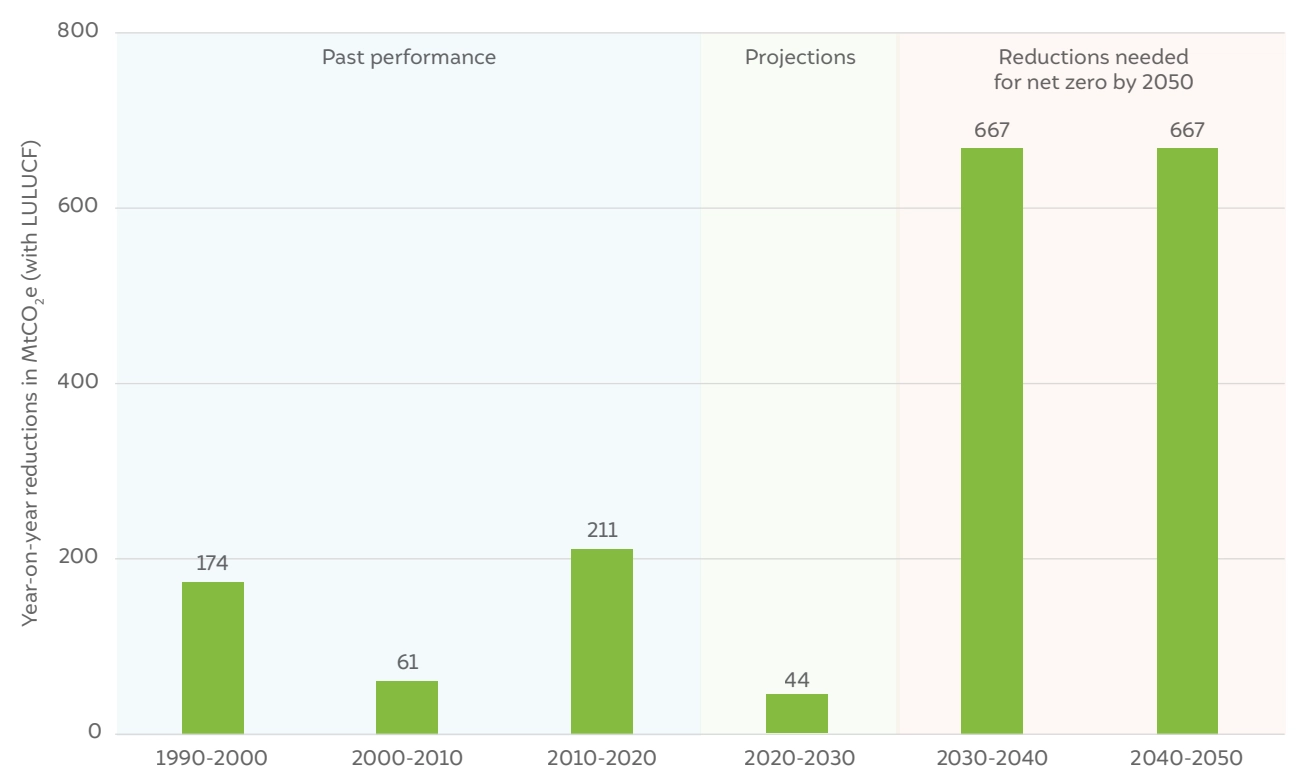

Figure 3 Emission reductions (with LULUCF) by developed countries before and after the critical decade (2020-30)

Source: Authors’ analysis

By 2020, the developed countries (Annex I) had achieved emission reductions of 24 per cent (when including LULUCF) from their 1990 levels. Figure 3 shows that considering current projections, this number will not be drastically different by 2030. In fact, given that progress is minimal, by 2030, emissions are set to reduce by 27 per cent from their 1990 levels. In other words, according to the projections, the ‘critical decade’ (i.e., 2020–2030) will not see deep emission cuts by developed countries as a group. This has implications for the feasibility of achieving net zero by 2050, to which we turn next.

Net zero has evolved to become one of the most prominent concepts in defining climate ambition. As of 4 October 2023, 151 countries – which contribute to 88 per cent of global emissions – pledged or proposed a net-zero target (Net Zero Tracker, 2023). By pledging to reach net zero in 2050, several developed countries have claimed to be in line with the collective objective of limiting global warming to 1.5°C. Most notably, the US and the EU have used their 2050 net-zero targets to claim that their ambitions are fully in line with the 1.5° target (European Commission 2022; White House 2021). But are developed countries on track to meet these aspirational targets? And does the achievement of net zero by 2050 always translate into being in line with the 1.5° target?

Drawing on official self-reported projections of emissions in 2030, in this section we analyse whether the developed countries are on track to meet net zero by 2050.

The projected combined average year-on-year emission reduction for developed countries in the critical decade 2020–2030 is about 44 MtCO2e per year, which is less than the average for the previous three decades in 1990–2020 (see Figure 4).

Figure 4 Net-zero goals rely on drastic emission reductions post-2030

Source: Authors’ analysis

Note: This figure shows year-on-year emission reductions in MtCO2 e (including emissions from LULUCF) averaged over a decade for a) past performance in the three decades since the adoption of the UNFCCC (based on greenhouse gas inventory data); b) projected performance in the critical decade (based on self-reported projections); and c) the implications for emission reduction performance needed after 2030 (illustrated by year-on-year reductions if developed countries move linearly to zero by 2050 from 2030 emission levels). In this figure, the low emissions in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic may have inflated the year-on-year reductions in 2010–2020 and deflated it in the decade 2020–2030 decade in a zero-sum manner. However, this does not change the actual emission reductions necessary after 2030 to achieve net zero.

Based on the projections data (and Table 2), developed countries are set to collectively emit 13.3 GtCO2e in 2030. To move from this level to net zero by 2050 in a linear fashion, average year-on-year reductions of 667 MtCO2e are needed from 2030 onwards. This is more than four times the average year-on-year reductions achieved from 1990–2020. Figure 4 shows that developed countries will need to drastically scale up their efforts after 2030.

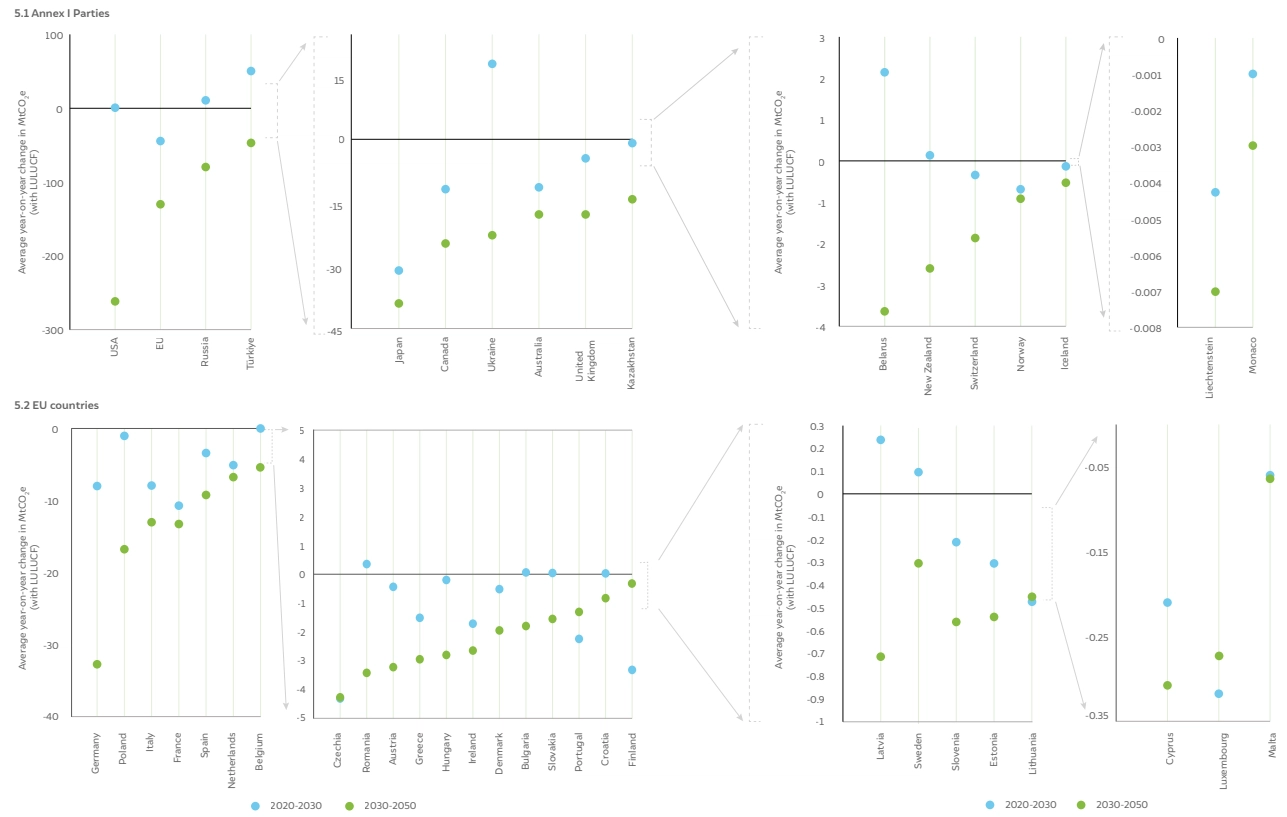

Figure 5 shows how individual countries are progressing towards net zero. The blue dots indicate the projected average year-on-year change in emissions in this critical decade. The orange dots show what this implies for the average year-on-year change in emissions needed after 2030 to achieve net zero by 2050. The general trend suggests that given current projections, most countries will have to ramp up climate action after 2030 to meet their net-zero targets by 2050.

Figure 5 Developed countries rely on large emission reductions after 2030 to meet net zero by 2050

Source: Authors’ analysis

Note: This figure shows the projected year-on-year change in emissions for the critical decade (blue dots) and the year-on-year change in emissions that would be required after 2030 to meet net zero by 2050 based on current projections (green dots). When the blue dot is below the green dot, it means that the country is moving at a pace of emission reduction in this critical decade that does not require any further acceleration after 2030 to meet net zero by 2050 (i.e., the country is on track). If the blue dot is above the green dot, it means the country will have to ramp up reductions after 2030, from the level of the blue dot to that of the green dot (i.e., the country is not on track). The year-on-year change in emissions differ substantially between large and small countries. One can imagine that the United States and a small country like Monaco have very different emission levels. This makes it hard to plot them in one graph. This is why the graphs are split up to allow for different y-axis ranges. The arrows give a visual illustration of this difference in range.

Figure 6 Enhanced climate action by developed countries is imperative in this critical decade

Source: Authors’ analysis

Only five developed countries – the Czech Republic, Finland, Lithuania, Luxembourg, and Portugal – are linearly on track to achieve net zero by 2050. This means that if the rate of emission reduction in this critical decade is sustained, the country will reach net zero by 2050. However, these five countries represent less than 2 per cent of the developed countries’ emissions in 2020.

All other developed countries are banking on accelerating action after 2030. For example, to achieve net zero by 2050, the United States would have to reduce emissions by 262 MtCO2e every year. This is more than the total annual emissions of Spain (which, in 2020, amounted to 228 MtCO2e) and more than twice the rate of reduction the US has ever achieved in previous decades (the record is 106 MtCO2e in the decade ending with the COVID-19 pandemic). The EU, as per the projections we analysed, would need to cut emissions by 127 MtCO2e every year after 2030 to achieve net zero by 2050. This is almost twice the rate of reduction the EU has ever achieved in previous decades (the record is 76 MtCO2e in the decade ending with the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, even if developed countries manage to accelerate after 2030 and move linearly to net zero, their cumulative emissions would still put the achievement of the 1.5°C goal at risk.Figure 6 shows that under current 2030 projections and linear reduction to net zero after 2030, developed countries are set to reach cumulative emissions of 265 GtCO2e by 2050. The remaining global carbon budget, starting from 2020, is estimated at 500 GtCO2 (for a 50 per cent chance to stay below 1.5°C temperature rise). We estimate that developed countries are set to emit 40-50 per cent of the remaining carbon budget, even if they achieve net zero by 2050. With about 80 per cent of the world’s population living in developing countries – and this figure is likely to increase slightly by 2050 (UNCTAD, 2022) – our estimates show that developed countries are set to emit more than their fair share in the years to come.

The climate journey of developed countries – historical and proposed – does not show deep enough emission reductions to reflect climate leadership. Even though this period (2020–2030) is the critical decade, developed countries are not projected to meet their 2030 NDC targets. Their failure to execute the necessary pre-2030 actions has implications for the limited global carbon budget. This means that the burden to mitigate global warming shifts to developing countries – which is problematic in a context where financial support to developing countries to achieve this transition has not been forthcoming, as promised. We present five key action points to course-correct.

The carbon budget represents the total amount of CO2 that can still be emitted before global temperatures exceed a certain threshold. The sixth assessment report of the IPCC estimated that by the end of 2019 the remaining carbon budget was 500 GtCO2 for a 50 per cent likelihood of keeping temperature rise below 1.5 °C.

The Paris Agreement features an 'enhanced transparency framework'. Under this framework, countries must submit reports containing information on their greenhouse gas emissions, mitigation and adaptation actions, as well as climate finance provided and received. These reports subsequently undergo technical review and a process of peer-to-peer presentation.

Climate mitigation strategies are policies and measures implemented by governments with the aim of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Examples include the implementation of a carbon tax, providing subsidies for green technologies, and enforcing regulations on emission standards.

Developed countries have several avenues to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. A crucial aspect of greenhouse gas reduction involves the phasing out of fossil fuels as a primary energy source, in favour of adopting greener and more energy-efficient technologies. Additionally, agriculture constitutes a significant source of emissions that can be mitigated through the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices and a shift towards more plant-based diets.

Under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) developed countries are required to submit Biennial Reports containing projections of their emissions in 2030. Such projections model most likely emission levels in 2030 based on a countries’ current (and planned) policies and measures. Before publication, these reports undergo a process of technical review. Because this information is reported by all countries, it provides a unique data source for analysis.

We used the latest available projections in the Biennial Reports as of 10 August 2023, but some countries highlighted (in their Biennial Reports) that their estimates do not cover the most recent policies. Note that some countries may have included more recent policies than others. Countries will submit the next round of projections in 2024.

Rethinking Ocean Governance in an Era of Climate Urgency

Operationalising the Loss and Damage Fund to Address Climate Impacts

Sustainability-driven Non-tariff Measures

The G20 Imperative for Global IP Reform To Facilitate Clean Energy Transitions