Suggested Citation: Elango, Sabarish and Hemant Mallya. 2021. Small-Scale LNG for Expanding Natural Gas Access in India. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

This issue brief discusses the potential for the growth of Small-Scale Liquefied Natural Gas (ssLNG) in India as the country moves towards increasing the share of natural gas in its energy mix to 15 per cent within a decade. Small-scale LNG can provide natural gas access to consumers without pipeline connections, or to those who operate outside areas of proposed city gas distribution network coverage. This study calculates the delivered price of ssLNG and finds that the fuel could be primarily price-competitive with diesel and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) used in industry, but could also compete with certain grades of furnace oil, pet coke and piped natural gas in certain locations. It makes a series of recommendations to aid the growth of ssLNG, whose limited market penetration in India is exacerbated by a lack of awareness amongst end users of the ssLNG option, limited ssLNG infrastructure growth, and policy support.

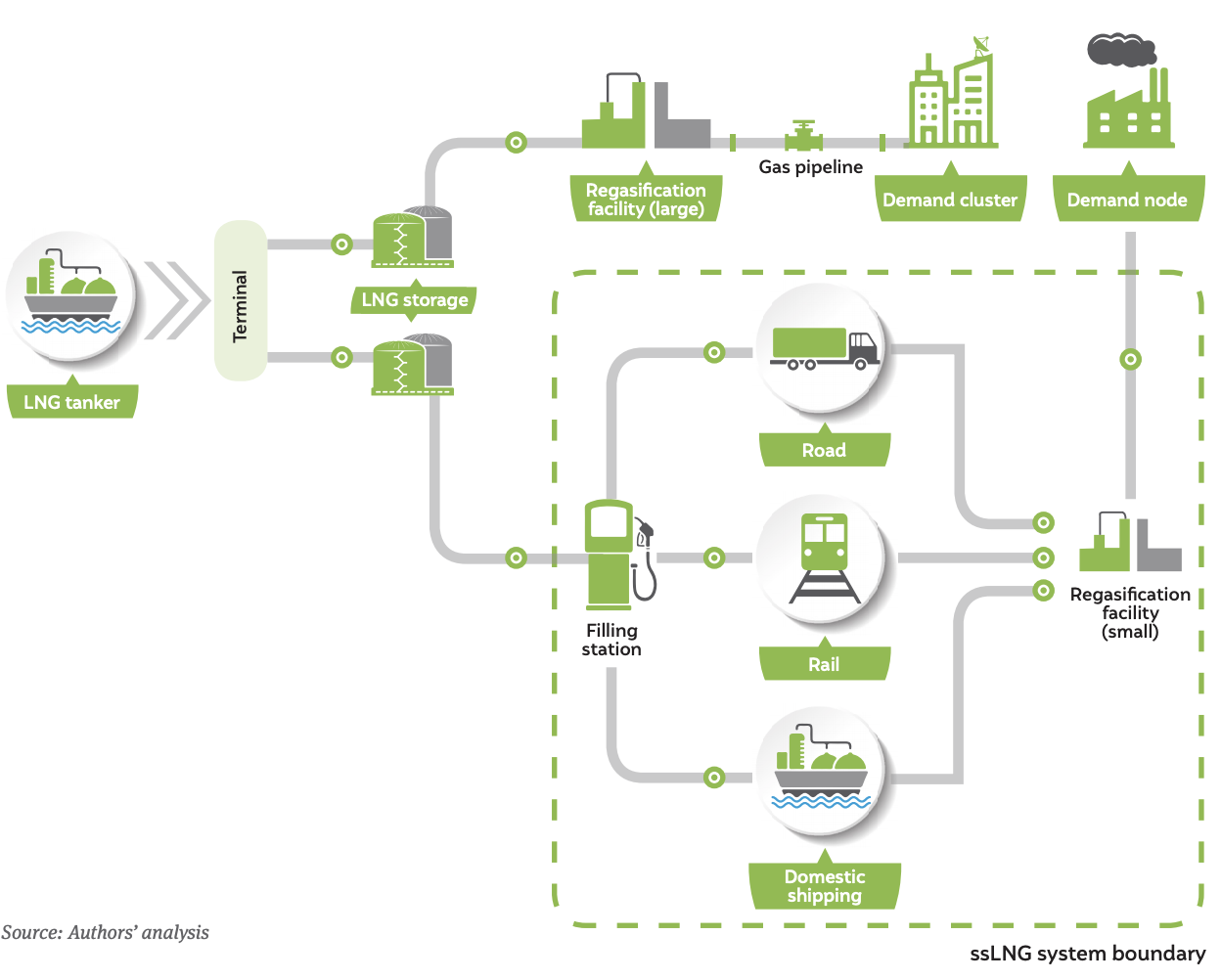

Small-scale LNG systems use road, rail, or waterways instead of transmission pipelines

Source: Authors’ analysis

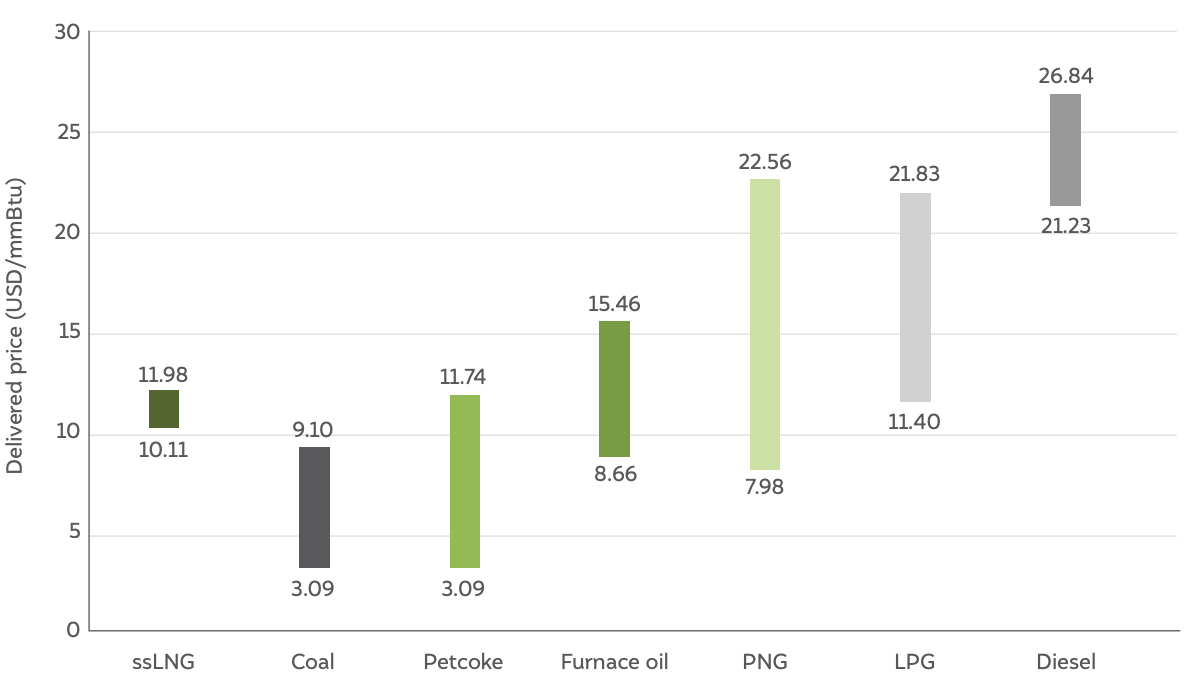

The delivered price of ssLNG compares favourably with several other fuels

Source: Authors’ analysis

Note 1: Prices for states in proximity to terminals - Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Odisha, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, West Bengal, Gujarat, and Rajasthan

Note 2: 10th and 90th percentile of prices considered to remove outliers.

Note 3: 2017-18 average LNG import price considered for ssLNG range due to lack of data on individual import cargoes

Natural gas has played an important role in mitigating emissions from several hard-to-abate sectors to address climate change in major global economies. However, natural gas has yet to contribute significantly to the primary energy supply in India, with only a 5.7 per cent share (IEA 2018). Distribution of natural gas in India relies primarily on a 17,000-kilometre network of pipelines for transmission from liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals and domestic production locations to consumers across different sectors.

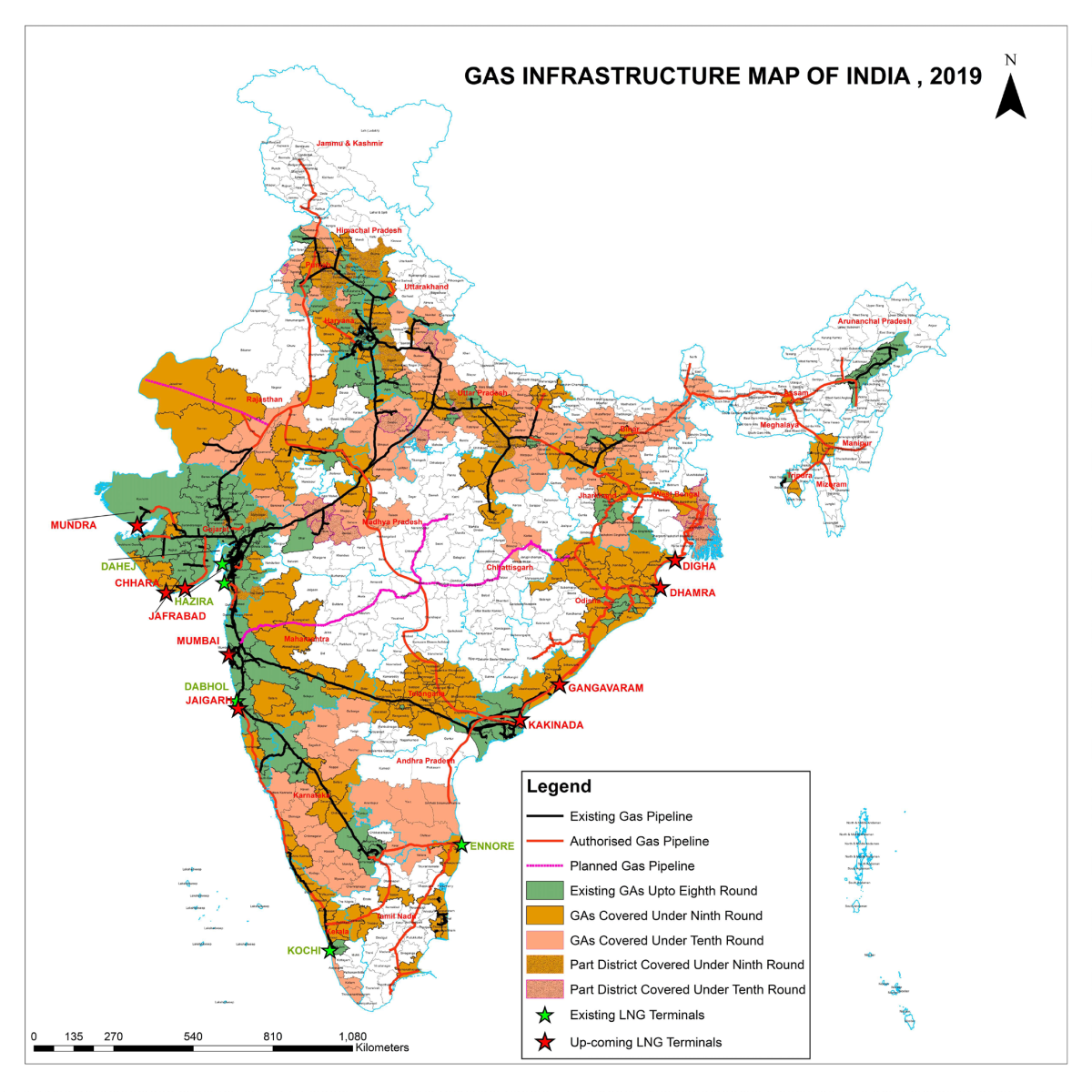

However, access to pipelines is limited in several southern and eastern states. Even the planned 15,000-kilometre (approximate) addition to the transmission network will not reach several potential gas consumers (Figure ES1). Transmission pipelines are expensive to construct and often require significant funding from the government to make them viable. Lengthy commissioning times and low capacity utilisation in the initial years of operation (as demand builds), experienced historically, are additional profitability stressors.

Figure ES1 Limited coverage of natural gas pipeline network in India

Source: PNGRB 2020a

Small consumers of natural gas rely on city gas distribution (CGD) companies to deliver natural gas from transmission pipelines. CGDs have infrastructure exclusivity in the areas allocated to them. Depending on the CGD pipeline network’s reach, consumers may not have access if they are located outside the CGD network’s range. Also, since the CGDs are allocated entire districts for gas distribution development, it takes much longer for low-density areas to receive a connection. The gas price charged by CGDs is often uncompetitive with incumbent fuels, considering the investments needed to be made by consumers to switch over to gas. Such issues have prevented the natural gas market from growing as anticipated.

Small-scale LNG (ssLNG) systems transport LNG in cryogenic containers and regasify the LNG at the consumer site. Delivering natural gas as ssLNG could be advantageous for those consumers

I. who are yet to be connected by gas pipelines,

II.whose location lies outside of any proposed coverage area of gas transmission or CGD pipelines,

III.or who cannot procure CGD gas at economical prices.

Small-scale LNG could provide potential consumers with temporary access to gas, thus helping build demand for pipelines. It could also serve as the primary source of gas if no pipeline connection is expected. Small-scale LNG would serve certain users such as large construction sites, mines, and quarries better than piped gas due to their fluctuating fuel needs. Small-scale LNG could also complement existing CGD connections for consumers to diversify supply options and optimise procurement costs. The use of LNG as a transport fuel for heavy-duty vehicles is being encouraged and supported by the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas (MoPNG). Small-scale LNG systems are essential to supply LNG to the numerous refuelling stations being planned across the country.

The ssLNG market could support investments from several stakeholders. LNG terminal operators could benefit by providing the transport and regasification service to enhance their reach and improve their capacity utilisation. Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) could gain from a commonly managed ssLNG system, with a local micro-grid network for gas delivery. Third-party companies could engage in volume aggregation of small consumers’ demand and provide doorstep delivery of LNG from terminal to consumer site, providing natural gas access to the small consumers.

Small-scale LNG can be delivered to consumers in four configurations —by the LNG importing terminal, the consumer’s own fleet of vehicles, a third-party logistics service provider, or a third-party aggregator. We evaluated the cost of moving ssLNG from the terminal to the consumer location and subsequently regasifying it for the second configuration. For the other configurations, there are increased efficiencies resulting from servicing multiple consumers. The marketing margins for these configurations are not available in the public domain. Hence, the cost of ssLNG is difficult to quantify. For this study, we calculated the prices for gas delivered through ssLNG systems for a 0.1 million metric standard cubic metres per day (mmscmd) regasification capacity over 20 years at different LNG import prices, for delivery distances from 200 to 1,000 km.

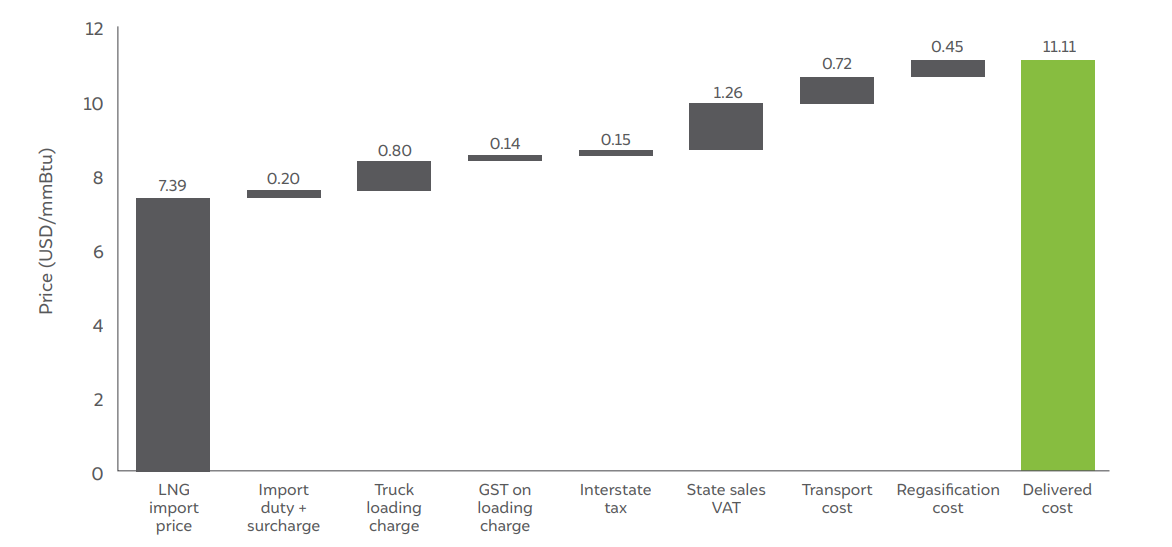

To estimate the delivered price of ssLNG, we considered the 2017–18 average LNG import price of 7.39 USD (INR 542) per million British thermal units (mmBtu) (PPAC 2020b). For this import price, the delivered price of regasified ssLNG was estimated at 11.11 USD/mmBtu (815 INR/mmBtu) for a one-way distance of 200 kilometres, and 11.98 USD/mmBtu (843 INR/mmBtu) for a one-way distance of 1000 kilometres. The price range of ssLNG is competitive with incumbent fuels such as liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), diesel, and certain petcoke and furnace oil grades as shown in Figure ES2. Gas delivered through ssLNG systems could potentially also be cheaper than CGD gas in many locations due to the high CGD selling price/margins. The price spreads between ssLNG and diesel/LPG are high enough to ensure short payback periods for transport and regasification infrastructure investment.

Figure ES2 The delivered price of ssLNG compares favourably with several other fuels

Source: Authors’ analysis

Note 1: Prices for states in proximity to terminals - Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Odisha, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, West Bengal, Gujarat, and Rajasthan.

Note 2: 10th and 90th percentile of prices considered to remove outliers.

Note 3: 2017-18 average LNG import price considered for ssLNG range due to lack of data on individual import cargoes.

The break-up of price for one-way distance of 200 kilometres is shown in Figure ES3. The break-up suggests that, apart from the LNG import price, major contributors are the truck-loading charges levied by the terminal, the value-added tax (VAT) applied on gas in the state of sale, and the cost of transporting LNG.

Figure ES3 VAT, loading charges, abd transport costs contribute significantly to the delivered price of ssLNG

Source: Authors’ analysis

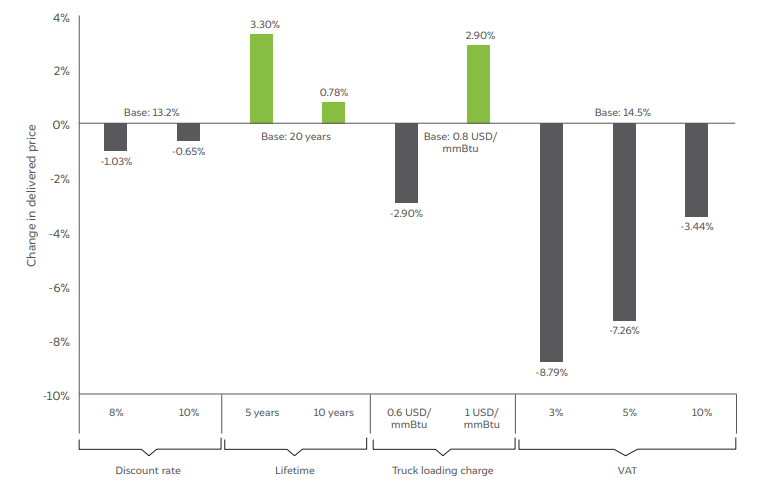

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to understand the impact of varying discount rates, the ssLNG system lifetime, terminal loading charges, and VAT (results in Figure ES4). The analysis shows that changes in the discount rate on the capital expenditure (CAPEX) of setting up an ssLNG system do not significantly impact the delivered price of ssLNG. The delivered price of natural gas through ssLNG increases for shorter project lifetimes - those setting up a temporary ssLNG system must pay a marginally higher delivered price. Still, the increase is not significant as the salvage value of the equipment has not been accounted for in this analysis. The delivered price of ssLNG varies proportionally with the changes in terminal loading charges. However, it is still not significant. Finally, reducing the VAT from 14.5 per cent (as in Kerala) to 3 per cent (as in Maharashtra) reduces the delivered price of LNG significantly, by 8–10 per cent.

Figure ES4 VAT has the highest impact among the considered sensitivity variables

Source: Authors’ analysis

Note: Sensitivities shown for an LNG import price of 6 USD/mmBtu and 200 km one-way distance.

Our analysis suggests that the low initial costs; competitive delivered gas prices; and scalability, flexibility, and movability of ssLNG infrastructure could be very beneficial for improving gas access.

There are some challenges associated with ssLNG systems, such as the possibility of transport disruptions (caused by inclement weather, accidents, etc.) and the limited LNG volume that can be supplied. Costs of retrofitting or re-engineering equipment for consumers to use gas, and the logistical and managerial constraints in the case of small industrial consumers, also pose some challenges. However, sound system design, resource management, and policy support can address these issues.

Several regulatory and policy actions can provide an impetus through ssLNG for the increased access and utilisation of natural gas. Such actions will allow India to move towards the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas’ (MoPNG) stated goal— to increase the share of natural gas in the country’s total primary energy supply (TPES) to 15 per cent by 2030.

1. MoPNG and PNGRB should clarify that ssLNG does not infringe on the infrastructure and marketing exclusivity of CGD on its own networks (in the geographic area allocated to that CGD), which will result in gas-on-gas competition and better price discovery, providing natural gas access at competitive prices to the consumers.

2. PNGRB should consider introducing a clause in the PNGRB Regulation G.S.R.198(E) that provides pipeline infrastructure exclusivity to CGDs for an exception to pipeline/distribution network connectivity within an industrial cluster. This will allow MSME clusters to source ssLNG, regasify it at a single location in the cluster, and distribute it through a pipeline network strictly limited to the cluster without infringing on the exclusivity rights of the CGDs.

3. A vital benefit of the ssLNG system is its standardised and modularised equipment, especially cryogenic tanks. The nodal agency for approving cryogenic tank design, the Petroleum and Explosives Safety Organisation (PESO), should approve the use of the International Organisation of Standardisation’s ISO 1496/3 design, which allows for the containerisation of tanks for the intermodal transport of LNG. PESO should also approve the transport of these containers on railway wagons.

4. India’s railway network is extensive and can potentially reach customers in locations with no existing or planned pipelines. The Dedicated Freight Corridors with faster travel times can significantly reduce the delivered cost of ssLNG. Therefore, the Indian Railways should develop specific tariffs for LNG transport and provide the necessary infrastructural support to haul LNG freight containers, both of which do not currently exist.

5. The VAT on natural gas sales varies widely across states. States can choose to reduce VAT on natural gas consumption (such as the three per cent rate in Maharashtra) while awaiting the transition of petroleum fuels to the goods and services tax (GST) system. States can selectively reduce VAT for small customers, such that the states’ revenue collection is not significantly impacted. Still, small industrial customers will be able to access natural gas.

6. The Sagarmala initiative should promote and support the use of natural gas as fuel for inland and coastal waterways transport. Using gas can eliminate fuel spillages from diesel engines in waterways and reduce air pollution in ecologically sensitive areas; ssLNG will play a crucial role by supporting the natural gas refuelling system along the waterways.

Assessing Effectiveness of India’s Industrial Emission Monitoring Systems

Evaluating Net-zero for the Indian Steel Industry

Evaluating Net-zero for the Indian Cement Industry

Accelerating the Implementation of India's National Green Hydrogen Mission

Best Practices in CEM (Continuous Emission Monitoring)