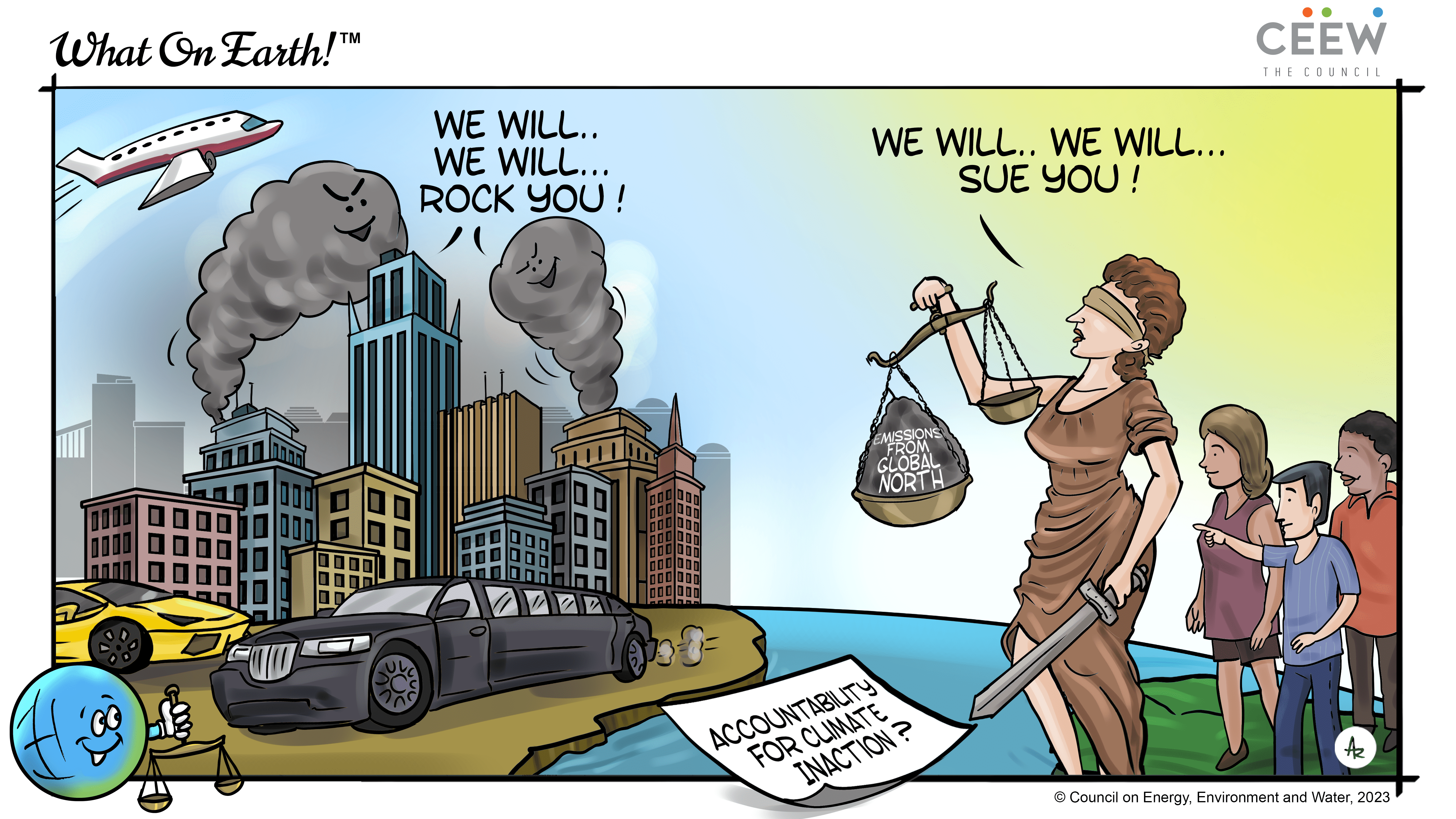

Can you take climate change to court? Or at least the historical polluters? The United Nations General Assembly’s recent adoption of a resolution seeking an International Court of Justice (ICJ) advisory opinion on climate change is a watershed moment that will strengthen legal accountability of climate actions and pledges. Such an advisory could enhance climate action, strengthen accountability, and encourage embracing climate justice in the existing legal frameworks, much like how the UN Declaration of Human Rights has been incorporated into statutes worldwide. This move was championed by the Republic of Vanuatu, a tiny Pacific nation that is grappling with the challenges of climate-related disasters.

So, how did we get to this stage? In short, lack of accountability in a fast-heating world. A study by the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) found that developed countries collectively exceeded their carbon space by around 25 gigatonnes (GtCO2e) in the pre-2020 period. Even with all the climate actions and pledges, the world is on track to see a 2.7°C temperature rise by the end of the century. Given the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), hiding behind a veil of inactions is no longer an option if the world’s future is to be certain. In light of this climate reality, the UN seeking ICJ’s opinion on legal redressal of climate change impacts comes as a ray of sunshine for enhancing accountability in a world where the delivery of past promises –in the form of emission reduction and finance–have been delinquent.

The lack of serious action and most importantly, missing accountability, has been rampant. Despite the presence of multiple climate legal instruments internationally, the efforts of the international community have been exiguous. For instance, the US, world’s second-largest emitter, did not participate in the Kyoto Protocol and also withdrew from the Paris Agreement (before joining back again in 2021). Additionally, Canada too dropped out of the Kyoto Protocol saying that the penalties would cripple its economy. This, as the Global South grows more and more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Such facts make it critical for the promised finance for adaptation and loss and damage to be enhanced and delivered upon urgently.

Further, in response to countries not meeting promises and pledges, a flurry of climate cases have emerged recently. Recently, a group of Swiss women have sued their government stating that the climate crisis violates their human rights. Dutch Airlines, KLM has been sued by environmentalists for greenwashing its carbon-offsetting scheme. There have been some wins too, for instance, the German court ruled that the government's efforts are inadequate to protect future generations and an upcoming coal project was rejected in Australia due to emissions and human rights’ concerns.

Given the current nature of climate governance and poor performance by developed countries in the past, we can no longer ignore accountability issues. The ICJ can offer two types of jurisdiction: contentious and advisory. While the former refers to settling legal disputes between states, the Court’s advisory opinion can offer viewpoints on legal questions to specialised bodies. They are non-binding, but carry paramount weight and authority. The draft resolution (A/77/L.58), in accordance with Article 96 of the Charter of the United Nations, asks the ICJ to consider two questions:

1) “What are the obligations of States under international law to ensure the protection of the climate system and other parts from GHG emissions for present and future generations?”

The overall objective of the Convention, the Paris Agreement goals, and the States’ commitments on climate action (mitigation and adaptation) and support will fall under its purview. It would be compelling to see how the advisory goes beyond the Paris Agreement and explores other declarations, including those of human and child rights, biodiversity, right to health and a clean and healthy environment from the lense of climate change to set the obligation of States.

2) “What are the legal consequences under these obligations where they, by their acts and omissions, have caused significant harm to small island developing states (SIDS) and people in particular?”

In light of the current architecture of international climate governance, strengthening climate accountability and its legal consequences are the need of the hour. This is imperative because the principles of the Paris Agreement – non-adversarial, non-intrusive, and non-punitive – do not allow navigating conversations in the direction of legal consequences. Further, this question limits the scope with a focus only on Small Island Developing states (SIDs). It would be important to see how developing countries and other groups (least developed countries (LDCS) and the Africa group) also impacted by the climate crisis are given equal consideration.

First, strengthen climate litigation through the use of attribution studies as legal evidence. Climate cases are complex as they demand establishing a number of causal links between the impact and its linkage with climate change. Research indicates that climate evidence used is usually lagging behind due to a lack of the latest science and information on events. This is where attribution science – that establishes a link between climate change and weather events – comes in and better informs such cases.

Second, draft model climate laws to enshrine international commitments. Australia has passed the Climate Change Bill that transforms its climate pledges into domestic law. Other nations too can draft such domestic laws that highlight the targets, the guidelines to achieve it, and the clear distinction of responsibilities across different levels of government. This ensures accountability of progress and pushes governments to comply in order to avoid judicial review. Further, the involvement of ICJ towards elaborating the legal consequences of climate acts could lead to more support for climate litigation and lawsuits at the domestic level.

The antidote to a failing climate order is accountability and cooperation. There is a need to truly reform multilateral mechanisms to facilitate global climate cooperation, call for accountability of both past and present actions, and strengthen climate litigation through use of attribution studies as legal evidence. While the resolution was not backed by the world’s two largest emitters – the US and China – this development still brings hope for strengthening climate governance. What we need are mature discussions on enforcement (adherence to climate agreement obligations) and accountability (acceptance of consequences on non-compliance), and most importantly, greater support and effort from wealthier countries.

Jhalak Aggarwal is a Research Analyst and Sumit Prasad is Programme Lead at the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), an independent, not-for-profit policy research institution. Send your comments to [email protected].

Add new comment