Suggested Citation: Malyan, Ankur and Vaibhav Chaturvedi. 2021. The Carbon Space Implications of Net Negative Targets. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

This study explores the implications of current pledges of advanced net-zero and net negative targets, set by 10 leading emitting nations, on the carbon space available for 1.5 °C and 2.0 °C temperature rise. It finds that the current net-zero pledges are enough only to keep the temperature below 2.0 °C and not below 1.5 °C. The ten leading emitters considered in the study would surpass the 1.5 °C budget by a significant margin.

If the United States, the European Union and China advance their net-zero targets by a decade, it could free up carbon space and yet miss the 1.5 °C goal. The study argues that these countries must target negative emissions instead of net-zero. With negative emission targets, cumulatively, these countries could sequester emissions, which meet the 1.5 °C target, while making space for the growth of developing nations.

The Paris Agreement was a landmark in the global climate discourse. The Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) submitted to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) under the agreement allowed countries to propose ambitious mitigation actions based on their national circumstances. However, collective ambition based on NDC commitments has been found to be inadequate to limit the global temperature rise to “well below 2°C” (UNEP 2020).

India is a climate leader that has delivered on its commitments. It has already installed more than 40 per cent of the non-fossil fuel electricity generation capacity target proposed under earlier NDCs. Now, the ambition has been set to 500 GW by 2030 (MoP, GoI 2021).

Further, it has made significant progress on its pledge to reduce, by 2030, the emission intensity of its GDP by 45 per cent compared with 2005 levels. In 2016, it had already reduced its GDP’s emissions intensity by as much as 24 per cent (MoEFCC 2021).

By contrast, the developed world has failed to deliver on its pre-2020 commitments. Since 2008, rich countries have emitted the equivalent of nine times India’s annual emissions over and above the limit they committed to (Prasad, Pandey and Bhasin 2021). The US, EU, China, and many developed countries have announced netzero targets in response to the need to stay below 1.5°C. However, evidence from the past raises concerns about their future course of action.

Net-zero targets are a sign of commitment to a low carbon world, but it is critical to understand whether the proposed pledges are sufficient. This is especially true at a time when most developing countries, including India, are negotiating for their right to development and their fair share of the global carbon space.

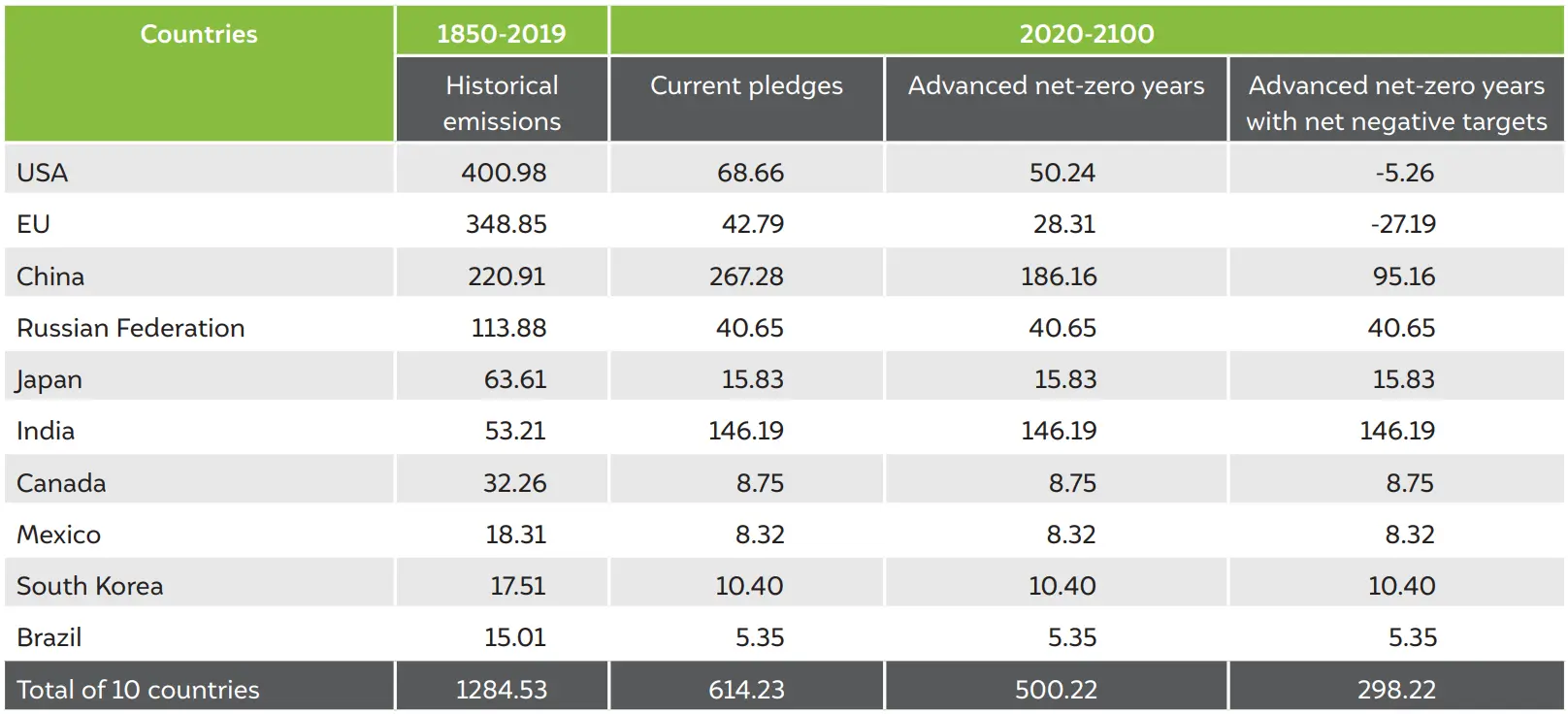

The Council on Energy, Environment and Water’s (CEEW) independent research explores the potential carbon space consumption by ten big emitters if they were on track to achieve their post-2030 commitments or current pledges. The table below describes the cumulative CO2 emissions, historical and future, across scenarios. The current pledges scenario reflects the existing NDC and net-zero targets. Whereas, the advanced net-zero scenario reflects the changes if the US, the EU and China advance their net-zero targets by a decade. The third scenario presents the emissions if these three nations, in addition to advancing their net-zero year, go for net negative targets in future (more details are presented in the methodology in the annexure).

The analysis finds that although China has proposed a 2060 net-zero target, it would consume 28 per cent and 10 per cent of the total global carbon space available for 1.5°C and 2.0°C targets, respectively, by 2030 . Additionally, by 2030, the US and the EU would consume 10 per cent and 6 per cent, respectively, of the space available for a 1.5°C target. They would consume 4 per cent and 2 per cent of the carbon space available for a 2.0°C target by 2030. Thus, between 2020 and 2030, these three regions would consume 45 per cent — and by 2050, 91 per cent — of the 1.5 °C carbon space. By midcentury, these regions would be consuming 32 per cent of the 2.0°C carbon space.

Though the committed 2070 net-zero by India is two decades later than the US and the EU and a decade later than China, cumulatively (1850-2100), it would emit 59 per cent less than China, 58 per cent less than the US and 49 per cent less than the EU.

Overall, these ten countries’ current NDC and net-zero targets and proposed pledges (refer annexure) would surpass the 1.5°C carbon space by 33 per cent by 2050. However, these pledges remain compliant to 2°C by 2100.

Cumulative CO2 emissions across countries and scenarios

Source: Authors' analysis

In case China, the EU and the US advanced their net-zero years by a decade, a significant share of the global carbon space would be freed up for the developing world. If China brought forward its net-zero year by a decade and peaked emissions in 2025, it would free up a staggering 81 GtCO2 of carbon space. The carbon space freed up if the EU and the US advanced their net-zero targets by a decade would be 14.5 GtCO2 and 18.4 GtCO2 , respectively. China, the EU and the US would be able to save 28.5% of the global carbon budget to stay below 1.5 °C, just by advancing their net-zero years by a decade.

The Government of India and many scholars have time and again emphasised the need for large developed economy polluters to become net negative by 2050 to free up additional carbon space for developing countries. If the three largest emitters — China, the US and the EU — sequestered additional carbon dioxide over and above the net-zero target, they would collectively sequester 202 GtCO2 between 2050 and 2100. This would free up significant carbon space for India and other Asian, African and Latin American nations to pursue their developmental agendas. This still implies that China’s post-2020 emissions would account for 23.8 per cent of the 1.5°C global carbon space. Ideally, the sequestration of carbon should begin much earlier to reduce the risks of breaching planetary tipping points.

It is evident that to stay below 1.5°C and distribute the global carbon space equitably, the world’s three largest emitters need to increase their emissions reduction efforts significantly. Their current net-zero targets simply do not meet the bar for climate ambition and explicitly violate the principle of climate justice. The analysis highlights that merely advancing the net-zero year will not be enough. These nations need to aim for negative emissions in the long term to support the growth of the developing world. The global net-zero agenda should shift to a net negative agenda for the developed world and China.

The analysis involved collecting historical emissions data, estimating future emission trajectories, and evaluating the share of carbon space consumed by the leading emitting nations. For this analysis, we have considered the following nations: China, the US, India, the EU, the Russian Federation, South Korea, Japan, Canada, Mexico, and Brazil. These countries were chosen based on their relatively high current share in total global emissions and the availability of explicit public information regarding their future vision and targets.

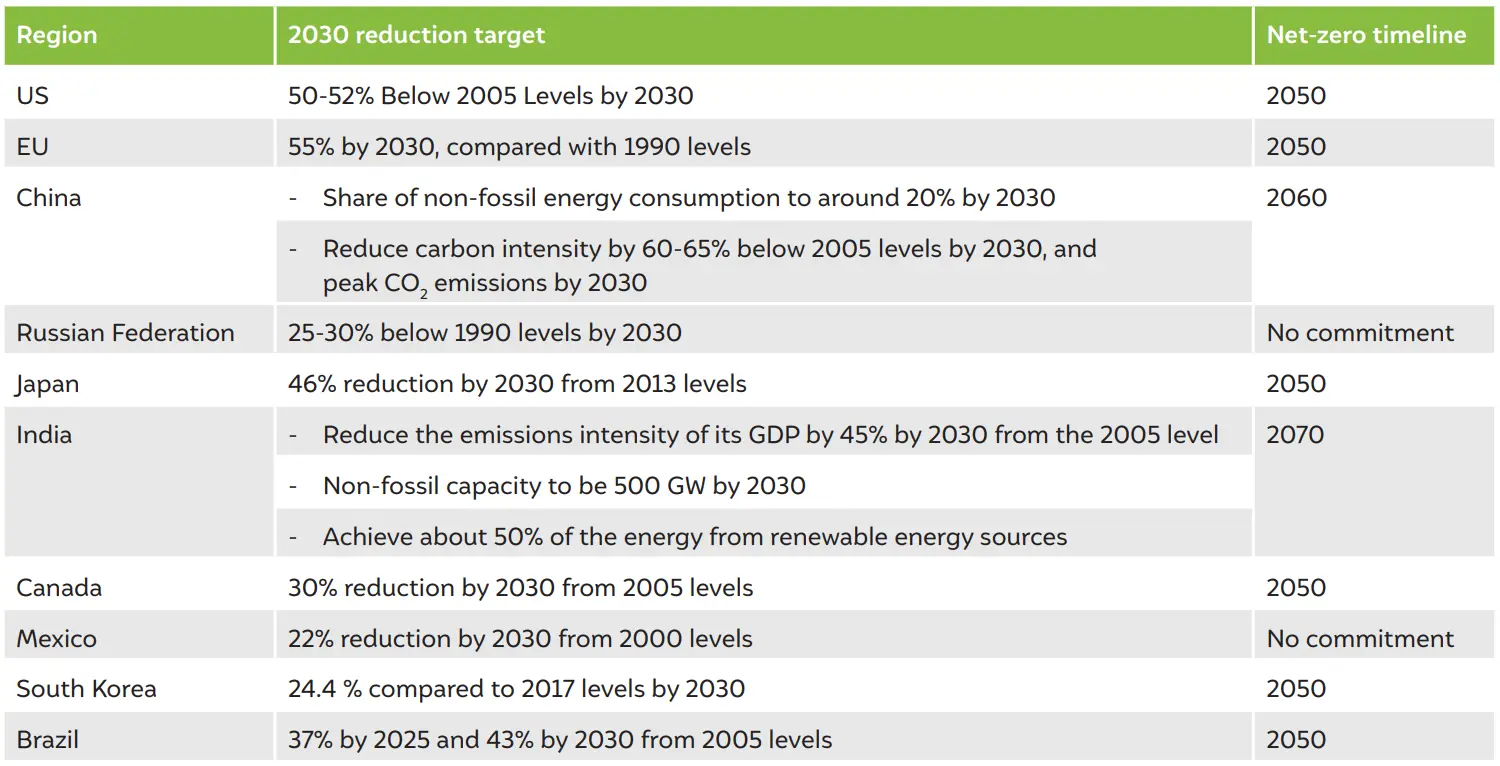

For the future trajectory of emissions, we considered the countries’ proposed pledges up to 2030. These included commitments under NDCs or any other mitigation efforts (see the table below).

To incorporate the NDC pledges mentioned above, we considered a linear decline in emissions between the 2021 emission level and emission targets up to 2030. Further, we assumed a linear reduction in emissions from 2030 levels to the net-zero year. India recently announced 2070 net-zero, which is considered in this analysis. As described in Chaturvedi and Malyan (2021), for the 2070 net-zero scenario for India, 2040 is considered as a peak year. Mexico and the Russian Federation have not taken a position on net-zero targets. For the analysis, we assume 2060 as the net-zero year for these two countries. However, it should not be assumed Mexico, and the Russian Federation will actually adopt these timelines, or that we recommend that they do so.

To understand the implications of advancing the net-zero years of the world’s three largest economies, we assume a 10-year advancement of the proposed net-zero years for the US, the EU, and China in our second scenario. We assume that the US and the EU target 2040 for achieving a net-zero economy while emissions decline starts immediately, and that China targets a 2050 net-zero year and advances its peaking year to 2025. However, other countries remain on the track considered in the current pledges scenario.

In the third scenario we considered, the US, the EU, and China countries not only advance their net-zero years but go on to achieve net-negative emissions. We assume that the US and the EU will sequester 1 GtCO2 starting in 2050, and that China will sequester 2 GtCO2 from 2060 onwards. We maintained the differentiation between the EU/the US and China is because of the massive size of the China’s energy economy. Between the net-zero year and the net-negative plateauing year, we considered the linear change in emissions.

Table A1 Emissions reduction commitments and long-term carbon neutrality targets for selected nations

Source: Authors' compilation

Tamil Nadu’s Greenhouse Gas Inventory and Pathways for Net-Zero Transition

The Emissions Divide: Inequity Across Countries and Income Classes

Implications of an Emissions Trading Scheme for India’s Net-zero Strategy

Demystifying Carbon Emission Trading System through Simulation Workshops in India