On 7 September 2020, the world celebrates its first-ever International Day of Clean Air for blue skies as resolved by the United Nations General Assembly last year. The appearance of blue skies amidst the COVID-19 induced lockdowns has spurred an increased interest in clean air. In the first two weeks of the lockdown, search queries related to air quality soared in India.

To ascertain the nature of this renewed interest in air quality, CEEW conducted an awareness and perception survey in central Uttar Pradesh (UP). The results indicate a rural-urban divide in awareness about air pollution and the level of education being a key determinant of this awareness. Besides, urban respondents are more perceptive of changes in air quality.

UP is among the most polluted states in the country, and its real-time air quality monitoring infrastructure remains inadequate. While UP requires 500+ monitors for its 200+ million population, it currently has 25 real-time (and 60+manual monitoring) stations, and all of them in cities.

We telephonically surveyed 400+ individuals of central Uttar Pradesh – 150 urban and 250 rural respondents, proportionate to the region's urban and rural populations.

The survey questions were structured to compare the proportion of urban and rural respondents who had heard of air pollution and whether their level of education, access to news and information, and nature of occupation had any bearing on this matter. We also wanted to assess whether both respondent categories were equally aware of air quality changes and if their perception indicators differed.

Urban-rural divide in awareness: Compared to 85 per cent of the urban respondents, only 63 per cent of the rural respondents had heard of air pollution. And a significant share of urban and rural respondents had heard of air pollution through electronic media and interactions with their family and friends (Figure 1).

Note: All values are in percentage

Level of education – a key determinant of awareness: On comparing our findings of the share of respondents who had heard of air pollution to that reported by two other multi-city air quality perception surveys carried out in 2017 and 2018, we found that our numbers were lower. The surveys report the awareness levels in cities of Uttar Pradesh to be over 95 per cent. That our survey found lower awareness levels could be attributed to the fact that compared to 60 per cent of the respondents in the other surveys, only 45 per cent of the urban respondents and 15 per cent of the rural respondents in our survey had a graduate degree.

We investigated this further by assessing the relationship between education and awareness of air pollution. Compared to 98 per cent of the respondents with a graduate or higher degree, only 62 per cent of the respondents without a graduate degree had heard of air pollution (Figure 2). Besides, 70 per cent of the respondents with only primary education had never heard of air pollution.

Note: All values are in percentage

A higher share of those engaged in indoor jobs had heard of air pollution compared to those with outdoor occupations and at the risk of higher exposure. (Figure 3).

Note: All values are in percentage

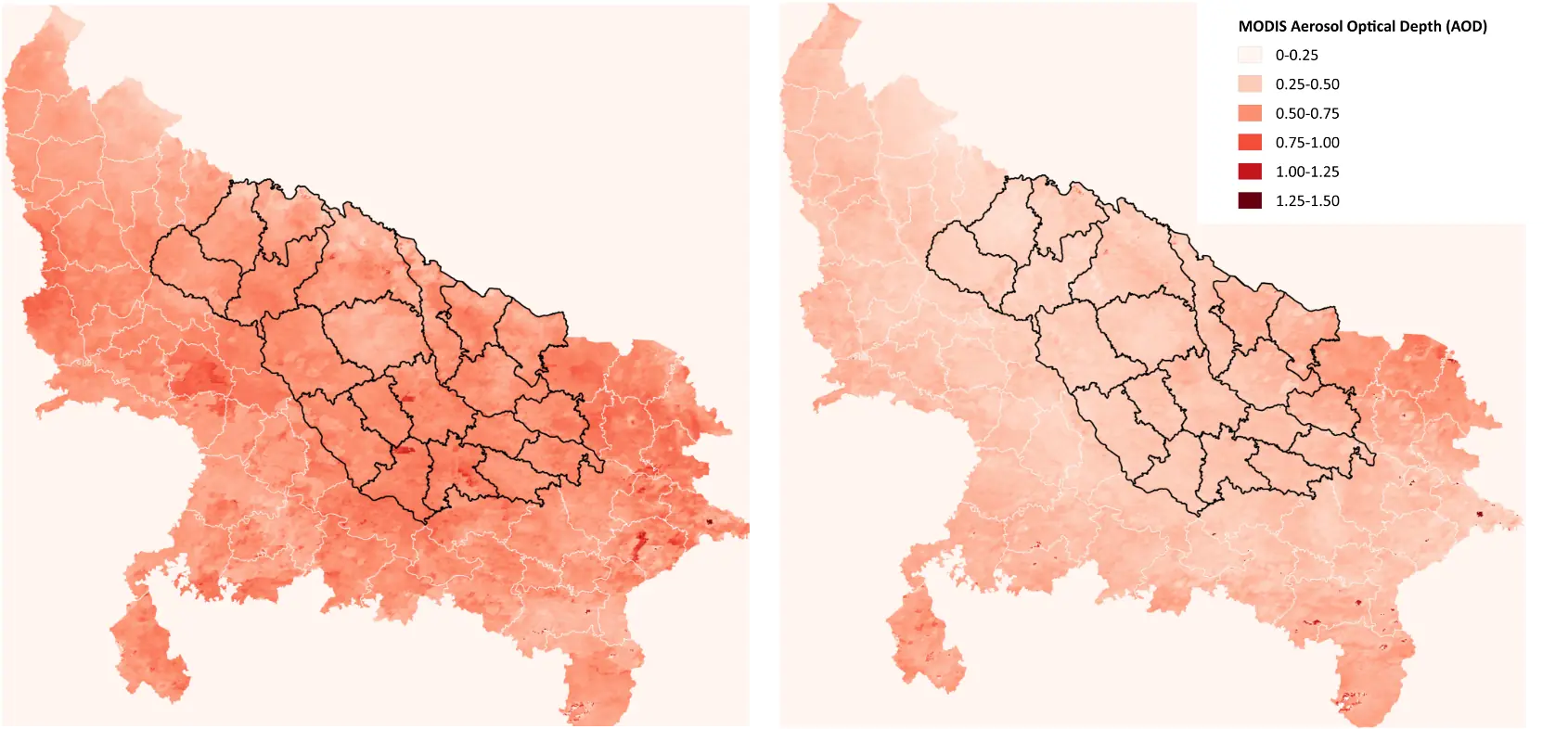

Urban respondents are more perceptive of changes in air quality: In the first two weeks of the lockdown, there was considerable improvement in UP’s air quality. As the state's limited real-time monitoring stations are in the cities, we used satellite-derived Aerosol Optical Depth (AOD) to assess the change in air quality across the rural areas during the lockdown. AOD is considered as a good proxy for PM 2.5.

As seen in Figure 4, in the first two weeks of the lockdown, there was a marked decline in AOD values across districts in UP compared to the AOD measurements between 1 – 24 March 2020.

Figure 4: District-wise AOD measurements for Uttar Pradesh

1 - 24 March 2020

25 March - 14 April 2020

Source: CEEW Analysis; MODIS MAIAC 1km AOD data accessed from Google Earth Engine (Lyapustin & Wang, 2015)

When asked if they perceived any improvements in air quality during the lockdown period, 76 per cent of the urban respondents, and 43 per cent of the rural respondents acknowledged the improvement.

As much as 88 per cent of the urban and 95 per cent of the rural respondents found the air in their vicinity to be generally clean. The limited few who complained of air pollution associated it with poor visibility, dust in the air, sudden discomfort in breathing, and higher Air Quality Index (AQI).

We found that only 37 per cent of the urban and 25 per cent of the rural respondents have heard of the Air Quality Index (AQI). This could explain their primary reliance on visual clues to gauge pollution levels.

Both the urban and rural respondents indicated motor vehicles and industries as the primary contributors to air pollution. Despite evidence suggesting significant reliance on polluting solid fuels1 such as firewood and dung cake as primary cooking fuels in rural Uttar Pradesh, less than ten per cent of the rural respondents consider the use of solid fuels as a source of air pollution.

Pollution and its impact: Our assessment finds that 90 per cent of the respondents who had heard of air pollution also knew it triggered breathing discomfort, irritation in the eyes and throat, and residue in nasal passages. But, more than one-third of them did take any precautionary measures against pollution.

The clean air plans for non-attainment cities in UP list the dissemination of AQI on a real-time basis as a priority action. Our findings suggest that a significant share of respondents has not heard of the AQI. Therefore, it would be imperative to supplement the dissemination of AQI with the relevance of the metric.

Sustaining clean air consciousness and creating a democratic demand for clean air rests on increased awareness at all levels and across all walks of life. Having heard of air pollution doesn't help if people don't know how to respond to toxic pollution levels. Discussions on air pollution need to go beyond classrooms, seminar halls, and zoom windows to urban slums, villages, farms, and beyond.

Tanushree Ganguly is a Programme Associate and L.S. Kurinji is a Research Analyst at the Council on Energy, Environment and Water. Send your comments to [email protected]

1 In the absence of monitored data on rural air quality, satellite-based estimates suggest that biomass burning for cooking and heating, agricultural fires, and brick kiln operations in the rural areas, especially in the Indo-Gangetic plain, cause poor air quality.

Add new comment