Suggested citation: Malyan, Ankur, Poonam Nagar Koti, Nitin Maurya, Diptiranjan Mahapatra, and Vaibhav Chaturvedi. 2021. India’s Natural Gas Future Amid Changing Global Energy Dynamics. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water

This study discusses what it means to be a gas-based economy in the Indian context. It presents insights on gas penetration across sectors, requirements for gas infrastructure and investment, employment opportunities, implications on import bills, and emission reduction in each scenario.

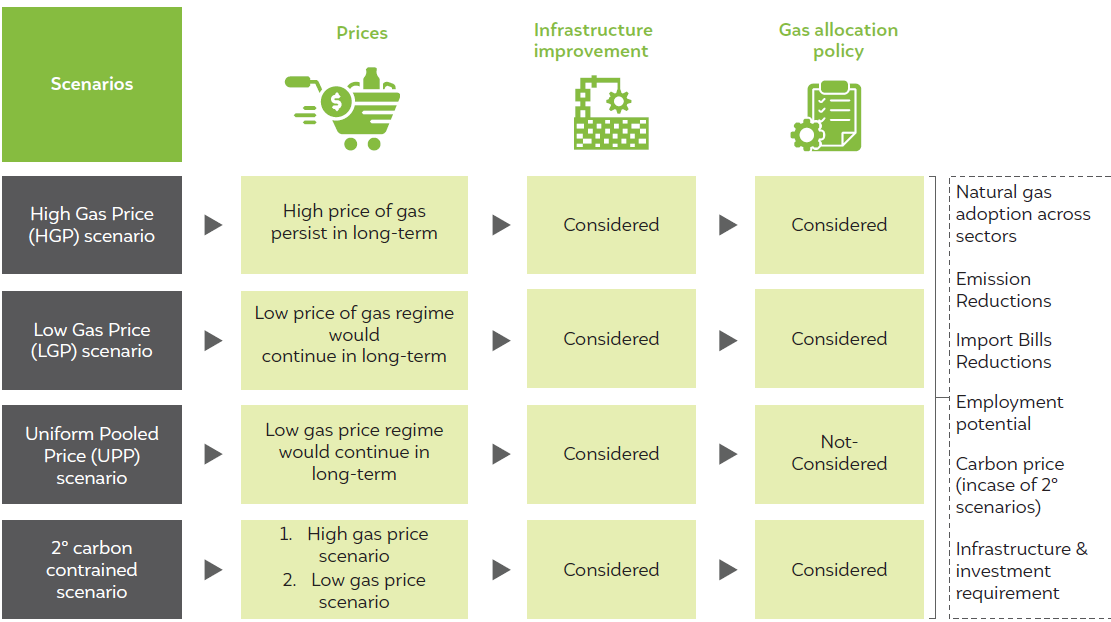

The study highlights the implication of a changing global gas price dynamics on India’s ambition of being a gas-based economy using integrated assessment-based scenario analysis. It explores four scenarios for natural gas in India: (i) ‘High Gas Price’ (HGP) scenario that is also our Reference sc; (ii) ‘Low Gas Price’ (LGP) scenario; (iii) ‘Uniform Pooled Price’ (UPP) scenario (for testing an alternative gas allocation policy); and (iv) ‘Low-carbon 2-degree’ scenario, for reflecting a low carbon world.

Figure 1 describes the scenario framework for the study.

Source: Authors’ compilation

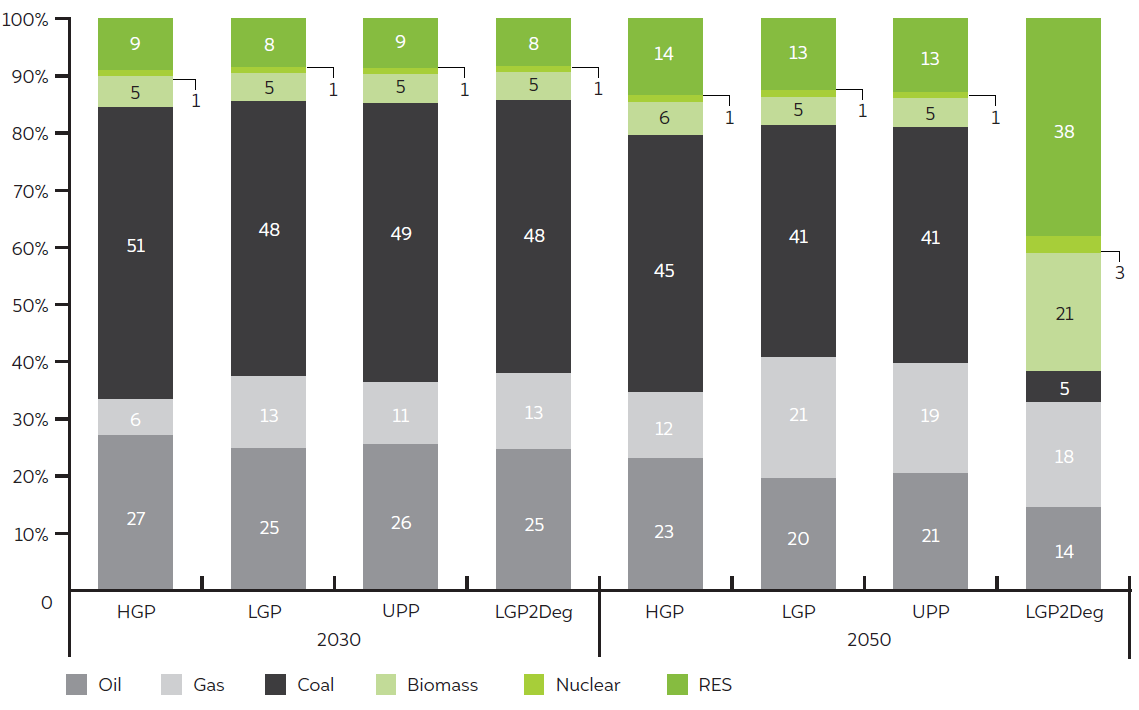

Figure 2: In low gas scenario, by 2050, natural gas could support one-fifth of the total primary energy demand

Source: Authors' compilation

Note: RES refers to summation of energy provided by RE resources, namely solar, wind, hydro and geothermal

This study traces the potential evolution and adoption of natural gas in the Indian economy, across sectors. The insights are crucial to understanding alternative pathways which natural gas could take under different price regimes and the 2-degree carbon-constrained scenario. India has been historically facing high gas prices across sectors. Additionally, the nation has adopted a gas allocation policy to support some priority sectors such as CGD, fertiliser, and power. Due to globally declining natural gas prices, India is shifting from an HGP to an LGP regime. It is clear from Section 4.1. that while remaining in the HGP regime, India does not fulfil its goal of being a gas-based economy. Though the target of 15 per cent natural gas in the primary energy mix would not happen under an LGP regime, the margin is as low as 2 per cent in 2030, and the penetration would be around 21 per cent in 2050. Hence, it is evident that low gas prices offer great potential for gas adoption, but infrastructure remains a hurdle. However, the increasing share of gas doesn’t mean that the importance of coal diminishes for the Indian economy. In the LGP regime, the share of coal remains to be around 40 per cent in the primary energy mix. As already highlighted, the electricity generation sector does not uptake gas in a big way and, hence, has to rely on coal and renewable sources such as solar. Due to this, the Indian economy could have a high share of gas, but remain coal dominated irrespective of the global gas scenario.

Section 5.1. highlights that the massive deficit of infrastructure in terms of pipelines and LNG capacity could restrict the gas adoption potential of the Indian economy in the LGP regime. Hence, the key is to expedite infrastructure development to harness the LGP opportunity. Our findings align with those of Sircar, Sahajpal, and Yadav (2017), who have highlighted various regulatory challenges that need immediate attention in order to facilitate the expansion of gas infrastructure. Another way to expedite infrastructure development could be more frequent bidding on geographical areas to expand the area under coverage and increasing investments.

Whether a gas allocation policy should exist in India has been debated on numerous platforms. The results of this study show that the withdrawal of the gas allocation policy would lead to a decline in the gas penetration in the Indian economy and across sectors. Priority sectors would have to give up their share of natural gas in the uniform pooled price scenario due to the higher price of gas that would be faced by these sectors as compared to the current policy regime. Having said that, we argue that market reforms are critical, and there are many potential benefits to the economy in the move towards a market friendy structure for the allocation of natural gas. A potential decline of gas use in sectors that are currently in the priority list should not be used as a rationale to scuttle market reforms which could be counter-productive. While in theory, it is simple to withdraw or retain this policy, the Indian economic system is highly complex, and the impact of a withdrawal needs a separate, detailed analysis. The reason for the existence of this policy is also linked to the volatility experienced by end consumers, such as farmers in the case of the fertiliser sector. Thus, the study only highlights the implications of withdrawing the gas allocation policy on gas penetration but not the other related aspects that are important to consider while making a decision on this policy.

The role of gas penetration in decarbonisation goals has been highly debated, and this study tries to provide insights to further and inform some aspects of the discourse. The global scenarios talk about two extremes: either that gas is a transition fuel that helps with decarbonisation or that it impedes low-carbon transitions and makes deep decarbonisation much more difficult. The study highlights that the high penetration of gas (as in the LGP scenario) in the Indian context would neither have a significant positive impact on the emissions trajectory nor make deep decarbonisation much more difficult. The LGP scenario shows that the cost of mitigation also increases marginally by 4 per cent with high gas penetration. But high gas penetration would also include employment generation potential— approximately 1.2 lakh new job opportunities— and provide significant savings in import bills of around 723 billion (2015 USD) sum of undiscounted cost from 2020 to 2050. The deep decarbonisation scenario supports the penetration of electricity across sectors but reduces gas penetration. In this case, the infrastructure built to cater to the demand in an LGP scenario, requiring massive investments, could get stranded. The possibility of a restricted carbon budget could increase the risk of investments, and stranded assets would harm investors in the long run. Thus, it is crucial to establish an optimal balance point between deep decarbonisation and high gas penetration. This study argues that the LGP scenario in a carbon-constrained world can significantly benefit the economy. We find that 18 per cent natural gas share in India’s primary energy mix by 2050 is an optimal to reap benefits of low gas price opportunity while meeting country’s decarbonisation objectives.

Like any study, our research is not without its limitations, which we foresaw and propose that future researchers consider. Aspects such as the implication of withdrawing gas allocation policy for downstream consumers, such as farmers, in a low gas price regime are yet to be examined. In this study, we did not explore changes in tax regimes, but with upcoming dynamic changes in the taxation system, it becomes relevant to consider the implications of different tax options for the competitiveness of natural gas across sectors. Additionally, the role of gas in hydrogen feasible world can also be explored considering the optimistic developments in hydrogen breakthrough.

Tamil Nadu’s Greenhouse Gas Inventory and Pathways for Net-Zero Transition

The Emissions Divide: Inequity Across Countries and Income Classes

Implications of an Emissions Trading Scheme for India’s Net-zero Strategy

Demystifying Carbon Emission Trading System through Simulation Workshops in India