Suggested Citation: Wadhawan, Shreya. 2023. Strengthening India’s Disaster Preparedness with Technology: A Case for Effective Early Warning Systems. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

Early warning systems (EWS) can improve resilience against climate-related hazards by providing information for early action. However, to be effective, EWS must incorporate aspects of resilient systems. This study attempts to assess the effectiveness of nationally operated EWS and multi-hazard early warning systems (MHEWS) in mitigating the impacts of hydrometeorological hazards with a focus on floods and cyclones in India. To assess the effectiveness of EWS in India, the study proposes a novel 'vulnerability to resilience' model. This proposed model has two variables: first, vulnerability, based on the integrated vulnerability assessment framework established in a previous CEEW report, Mapping India’s Climate Vulnerability: A District-Level Assessment (2021), and second, resilience, based on the A2E framework, i.e., availability, accessibility, and effectiveness of EWS and MHEWS.

India is highly vulnerable to extreme climate events such as floods, droughts, and cyclones. A study released by the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) in 2021 found that 27 of 35 Indian states and union territories (UTs) are now vulnerable to extreme hydro-met disasters and their compounding impacts (Mohanty and Wadhawan 2021). Eighty per cent of India’s population resides in these vulnerable regions. However, India has been taking steps to build its resilience to the impacts of such extreme events by increasing preparedness and investing in early warning systems (EWS). These systems are being deployed throughout the world as essential instruments for disaster risk reduction (DRR). But, substantial gaps exist, especially in providing timely, comprehensible, and actionable warnings to the “last-mile”, i.e., the most isolated and vulnerable groups at the community level. To overcome these gaps, several UN General Assembly resolutions have emphasised the need for impact-based, people-centred, end-to-end multi-hazard early warning systems (MHEWS) to reduce vulnerabilities and build resilience (Briceno 2007).

At COP 27, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres unveiled an Executive Action Plan to provide Early Warnings for All, stating that "one out of three persons globally, primarily in Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and Least Developed Countries (LDCs), lack access to effective early warning systems" (Baker, et al. 2022). This plan requires an investment of USD 3.1 billion from 2023 to 2027 (WMO 2021) to make EWS available to everyone across the globe. EWS are designed to detect potential threats or hazards and provide advance notice or warning to individuals or organisations at risk. The launch of this Action Plan is a welcome announcement as the ten most expensive climate-related disasters in 2022 cost the world close to USD 170 billion in insured damages (Christian Aid 2021). Meanwhile, a report by the Global Commission on Adaptation found that spending just USD 800 million on EWS in developing countries could help avert losses worth USD 3–16 billion annually (UN 2022).

The study aims to assess the effectiveness of nationally operated EWS and MHEWS in mitigating the impacts for hydrometeorological hazards with a focus on floods and cyclones in India. To assess how EWS and MHEWS contribute to the resilience of Indian states, a novel vulnerability to resilience model has been proposed. Resilience within EWS is a function of

The availability of EWS and MHEWS in hotspot districts was assessed by conducting a thorough literature review of the available gray literature and an in-depth analysis of reports published by different government agencies.

To quantify the accessibility of EWS and MHEWS, the number of people covered through early warning dissemination systems were considered using the teledensity1 scope. The teledensity scope was quantified using the Telecom Subscriptions Reports– TRAI subscribers’ database (TRAI 2021) of both wireline and wireless subscribers for all telecom companies.

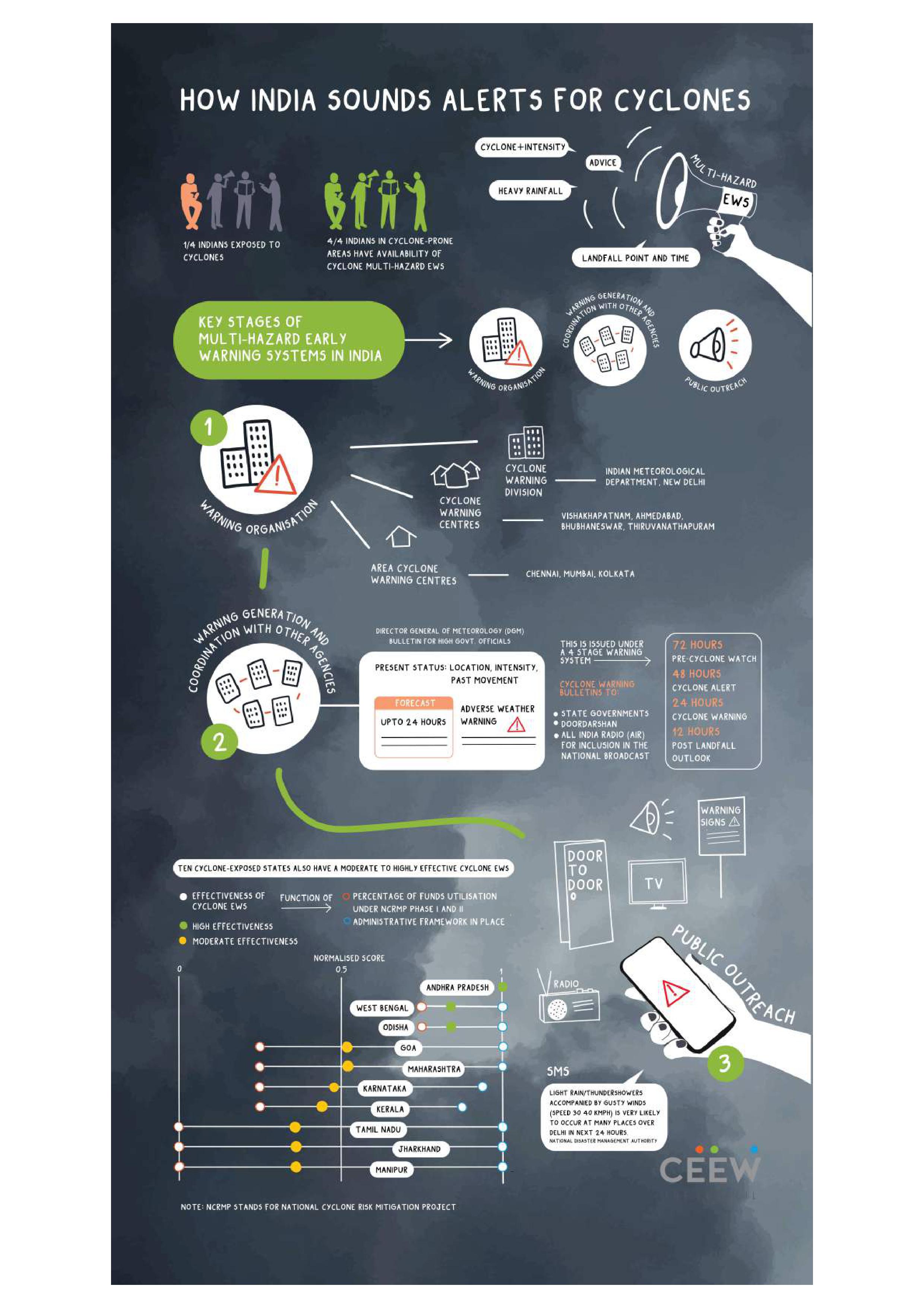

The effectiveness of EWS was evaluated using a systematic flow to comprehend the governance of the EWS at the national, state, and district levels.

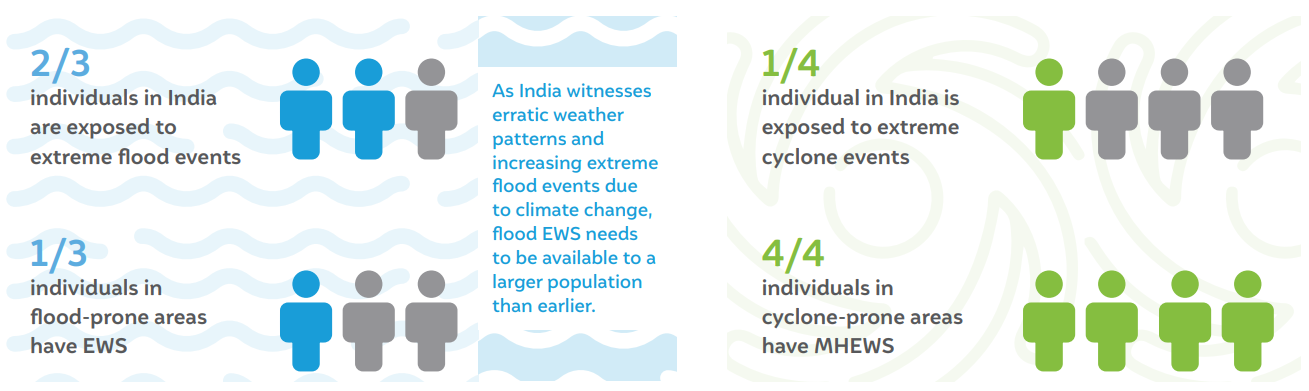

Figure ES1 Majority of people exposed to extreme floods have limited availability of flood EWS

Source: Author's analysis

Figure ES2 Majority of people in India have high means of accessibility to flood and cyclone EWS

Source: Author's analysis

The National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) of India has envisioned a CAP-based Integrated Alert System on Pan India basis. The project involves near real-time dissemination of early warning through multiple technologies using geo-intelligence (NDMA 2023).

Fostering public–private partnerships will accelerate innovation and the scaling of technological solutions for disaster risk reduction (DRR). Involving private companies can also aid fund mobilisation, bringing more transparency and accountability to the flow of finance towards EWS.

To ensure that climate change adaptation is incorporated into national and local DRR policies, we need to invest more in comprehensive disaster risk management. Establishing effective EWS is a low-hanging fruit in helping accomplish our DRR targets. Leveraging its position as the G20 presidency, India should promote the agenda of making early warnings available to all and champion impact-based people-centric MHEWS.

Early warning systems (EWS) are an essential tool for risk management and disaster preparedness that help save lives and minimise the potential impact of disasters. EWS do this by using a variety of tools and methods, such as sensors, data analysis, and communication channels, to gather information about potential threats or hazards and provide advance information or warnings to individuals or organisations that may be affected. Multi-hazard early warning systems (MHEWS) address several hazards and/or impacts of similar or different types in contexts where hazardous events may occur alone, simultaneously, cascadingly or cumulatively over time, and taking into account the potential interrelated effects. MHEWS, with the ability to warn of one or more hazards, increases the efficiency and consistency of warnings through coordinated and compatible mechanisms and capacities, involving multiple disciplines for updated and accurate hazard identification and monitoring for multiple hazards.

There are various ways of classifying EWS, such as by type of hazard, the level at which it is operated, and whether it is a single or multi-hazard system (UN-SPIDER 2021). Some examples of the types of EWS available globally include: 1. Weather and climate EWS: These systems are designed to provide advance notice of extreme weather events, such as hurricanes, tornadoes, and heat waves, as well as longer-term climate risks such as droughts and floods. They provide advance warning to local authorities and communities, allowing them to prepare and take necessary precautions. 2. Earthquake EWS: These systems use seismometers to detect potential earthquakes and provide warnings to people in affected areas. This can give people time to take shelter and protect themselves from potential damage. 3. Tsunami EWS: Similar to earthquake EWS, tsunami EWS use sensors to detect seismic activity in the ocean and provide alerts to coastal communities in the path of a potential tsunami. 4. Wildfire EWS: These systems use data on weather, vegetation, and other factors to estimate the risk of wildfires and provide alerts to nearby communities.

Effective “end-to-end” and “people-centred” early warning systems may include four interrelated key elements: 1. disaster risk knowledge based on the systematic collection of data and disaster risk assessments. 2. detection, monitoring, analysis and forecasting of the hazards and possible consequences. 3. dissemination and communication, by an official source, of authoritative, timely, accurate and actionable warnings and associated information on likelihood and impact. 4. preparedness at all levels to respond to the warnings received. These four interrelated components need to be coordinated within and across sectors and multiple levels for the system to work effectively and to include a feedback mechanism for continuous improvement. Failure in one component or a lack of coordination across them could lead to the failure of the whole system.

The key component of accessibility to early warning information is access to early warning dissemination systems (EWDS). Maintaining access to EWDS is crucial to ensure information is relayed and disseminated from the state, district, and block levels to communities and vice versa so that the last person nearest to the sea is well informed about taking appropriate action in case a cyclone or any other disaster occurs. Without accurate information, people are often forced to make crucial decisions based on unclear and conflicting reports. Therefore, there is an urgent need for speedy dissemination of disaster alerts to a maximum number of persons in order to ensure preparedness, both at the individual level as well as the responding institution level (NDMA 2021). Telecommunication services such as calls, messages, push messages, and other alerts are the most reliable and immediate way to relay early warning communication to the masses. However, it is essential to identify the most suitable method for information dissemination based on the needs and level of comprehensibility of the community. Dissemination techniques can be further categorised into widespread and targeted dissemination techniques, depending on where they are used and applied. While targeted methods can provide warnings to individual users, families, persons, neighbourhoods, predefined groups, agencies, etc., widespread methods (mass dissemination techniques) are less targeted and are primarily via the mainstream media through television and radio, loudspeakers, signs and sirens.

The 2019 Global Commission on Adaptation's flagship report, Adapt Now, found that EWS provides more than a ten-fold return on investment – far higher than any other adaptation measures included in the report. The report also found that issuing a warning just 24 hours before a coming storm or heatwave can cut the ensuing damage by 30 per cent. Furthermore, spending USD 800 million on such systems in developing countries would help prevent losses of USD 3–16 billion annually (UN 2022). Thus, investing in establishing an effective EWS will serve the dual purpose of saving lives and protecting economies while building long-term climate resilience. An effective EWS is the first step towards building resilience as it enables policymakers, public officials, administrators, and communities to plan ahead and safeguard lives and livelihoods. Under India’s G20 presidency this year, a working group on disaster risk reduction (DRR) has been formed for the first time since 1999. Further, EWS remains one of the key priorities throughout India’s G20 presidency. This is also in agreement with the Prime Minister’s Ten Point Agenda for DRR.

Heat Action Plan for Thane City 2024

Policy Study on Re-calibrating Institutions for Climate Action

Decoding India’s Changing Monsoon Patterns

The State of Extreme Events in India