Suggested citation: Mohanty, Abinash and Shreya Wadhawan. 2021. Mapping India’s Climate Vulnerability: A District-Level Assessment. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water

This study undertakes India's first-of-its-kind district-level climate vulnerability assessment. It presents a climate vulnerability index (CVI) of states and union territories by mapping exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity. A CVI would help to map critical vulnerabilities, and plan strategies to enhance resilience and adapt by climate-proofing communities, economies and infrastructure. Instead of looking at climate extremes in isolation, the study looks at the combined risk of hydro-met disasters and their compounded impacts on vulnerability.

The states located in India's northeast are more vulnerable to floods, while the states in the southern and central parts are more vulnerable to extreme droughts.

Our worst fears have been confirmed. Human-induced climate change is already causing severe weather events across the world, impacting the lives and livelihoods of millions. The first tranche of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report is a grim reminder of the make-or-break choices that we need to make in a 1.5°C-breaching climate.

The IPCC report reiterates the dire consequences of this human-induced breach for the Indian subcontinent: increased dry spells, intensification of extreme rainfall by more than 20 per cent, and an exponential surge in heatwaves and cyclonic events.

As global warming reaches a tipping point, India’s growth is linked intricately with climate risks. Such risks have a disproportionate impact on vulnerable communities with low adaptive capacities and pose a critical threat to India’s sustainable development. Investments in infrastructure such as housing, transport, and industries will be threatened, especially along the coasts. Further, with mounting weather-related insurance losses, climate change could trigger the next financial crisis.

This study undertakes a first-of-its-kind district-level vulnerability assessment of India, which maps exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity using spatio-temporal analysis. To do this, we developed a climate vulnerability index (CVI) of Indian states and union territories (UTs). A CVI will help Map critical vulnerabilities; Plan strategies to enhance resilience, and Adapt by climate-proofing communities, economies and infrastructure. Instead of looking at climate extremes in isolation, we map the combined risk of hydro-met disasters and their compounded impacts on vulnerability. By doing so, we aim to inform policy goals in the resource-constrained context of India.

India is the seventh-most vulnerable country with respect to climate extremes (Germanwatch 2020). Climate action needs to be scaled up both at the sub-national and district levels to mitigate the impact of extreme events. An analysis by the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) suggests that three out of four districts in India are extreme event hotspots, with 40 per cent of the districts exhibiting a swapping trend, i.e., traditionally flood-prone areas are witnessing more frequent and intense droughts and vice-versa (Mohanty 2020). Further, the IPCC states with high confidence that every degree rise in temperature will lead to a three per cent increase in precipitation, causing increased intensification of cyclones and floods.

This is especially concerning since global, regional, national, and subnational climate actions are geared towards limiting the rise in Earth’s temperature to 2 °C above pre-industrial levels. However, storms are already intensifying into cyclones, droughts are affecting more than half of the country, and floods of unprecedented scale are causing catastrophic loss and damage (Mohanty 2020). These trends are the result of a mere 0.6–0.7 °C rise in temperature in the last 100 years (IMD 2019). Thus, there is a pressing need to consider the consequences of a 2°C target.

Various studies by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the Department of Science & Technology (DST) have highlighted the importance of robust micro-level vulnerability assessments. Given the absence of such an assessment in India, this study undertakes an integrated mapping of exposure (the nature and degree to which a system is exposed), sensitivity (the degree to which a system is affected), and adaptive capacity (the ability of a system to adjust to climate change) using spatio-temporal analysis. Equation ES 1 enumerates the vulnerability function.

Managing climate risks requires an enhanced understanding of the underlying drivers of hazards; the exposure of regions and populations; the sensitivity of regions and their resulting vulnerability; and the interactions between these components, as highlighted by the IPCC. While exposure to extreme events is linear, the impacts are non-linear, depending on the sensitivity and adaptive capacity of the affected systems. For some, it may entail adjustments and re-adjustments in livelihood options, but, for others, the impacts can be catastrophic, compounding beyond existing vulnerability thresholds. Thus, identifying the compounding impacts of risk and mapping the vulnerability of geographies and communities is a national imperative.

Vulnerability (f) = (Exposure x Sensitivity)/ (Adaptive Capacity)

This study is a first-of-its-kind micro-level vulnerability assessment that maps the climate vulnerability of districts in India. To assess vulnerability, we designed a composite CVI for Indian states and UTs that considers exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity. The study evaluates exposure at the micro-level, assessing sensitivity through spatio-temporal analysis and analysing adaptive capacity by evaluating socio-economic and governance mechanisms. The framework we developed is based on IPCC’s SREX framework, which was also used by DST to map vulnerability to climate change.

As the CVI integrates spatial, temporal, and location-specific indicators, it enables the mapping of critical communities, sectors, and assets. It is unique in that it computes the vulnerability score of each district by taking into consideration all three components of the vulnerability function: exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity. Further, it explores the differential importance of each vulnerability indicator in determining the total vulnerability score using composite vulnerability indexing exclusively for hydro-met disasters. Table below enumerates the state-wise vulnerability indexing of Indian states.

The spatial index–based assessment will help mainstream climate actions through a robust decision-making (RDM)1 approach (Lambert, Sharma, & Ryckman 2019). Further, such a composite assessment can help determine policy goals and reprioritise climate adaptation actions in a resource-constrained country like India.

The assessment maps the frequency and intensity of exposure of Indian districts to hydro-met extremes and associated events. Further, these data are integrated with a spatial mapping of the sensitivity of landscape indicators (land-use-land-cover, soil moisture, groundwater, slope, and elevation) to climate extremes. We also assess adaptive capacity by considering a wide set of socio-economic indicators such as population density, GDDP, literacy ratio, sex ratio, availability and accessibility of critical infrastructures, availability and accessibility of shelters, and robustness of district disaster management plans (DDMPs). Extreme event indicators were shortlisted through stakeholder consultations to capture the on-ground consensus regarding the drivers of vulnerability at a micro-scale.

In line with the IPCC’s SREX framework and the DST common vulnerability assessment approach (DST 2020; IPCC 2014), we propose that climate extremes should not be seen as primary events; instead, the combined risk of associated events should be mapped. Thus, we capture the combined risk of hydro-met disasters and their compounded impact on districts’ climate vulnerability.

Assam, Andhra Pradesh, and Maharashtra are the top three climate vulnerable states in India

Source: Authors’ analysis

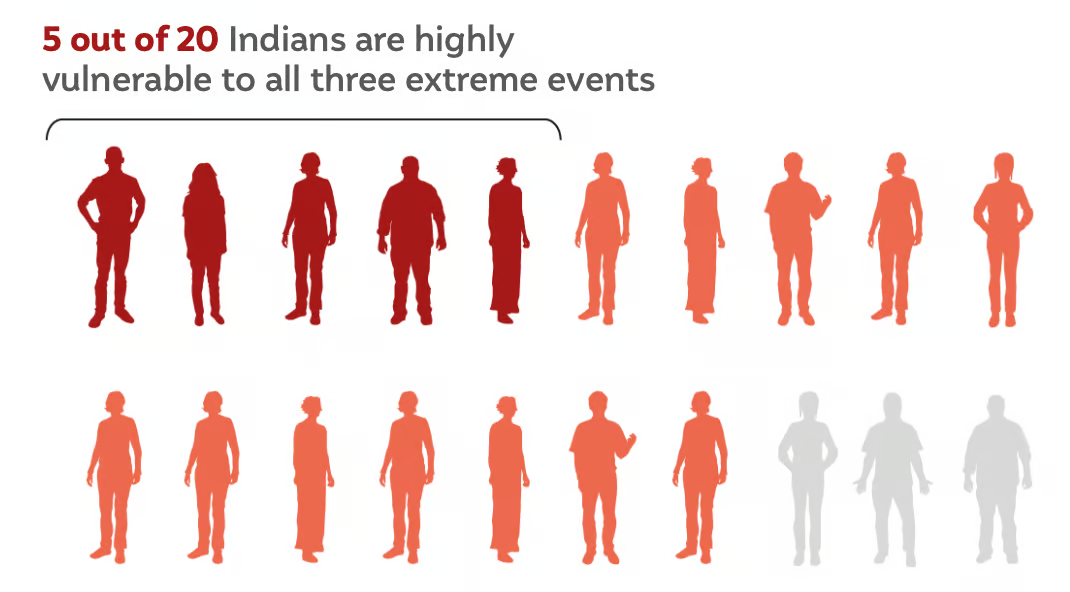

We find that the pattern of extreme events is changing across regions and that more than 40 per cent of Indian districts exhibit a swapping trend. Tackling these complex, varying patterns requires concerted risk mitigation strategies at the sub-national level. Our analysis suggests that the CVIs of Assam, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Bihar are in the high range, making them the five most vulnerable states in India. However, there are marginal differences in the vulnerability of these states, so it is imperative to step up climate action in all of them. The CVI also helps map the vulnerability of populations residing in Indian districts. We find that more than 80 percent of India’s population lives in districts highly vulnerable to extreme hydro-met disasters (Figure below).

Source: Authors’ analysis

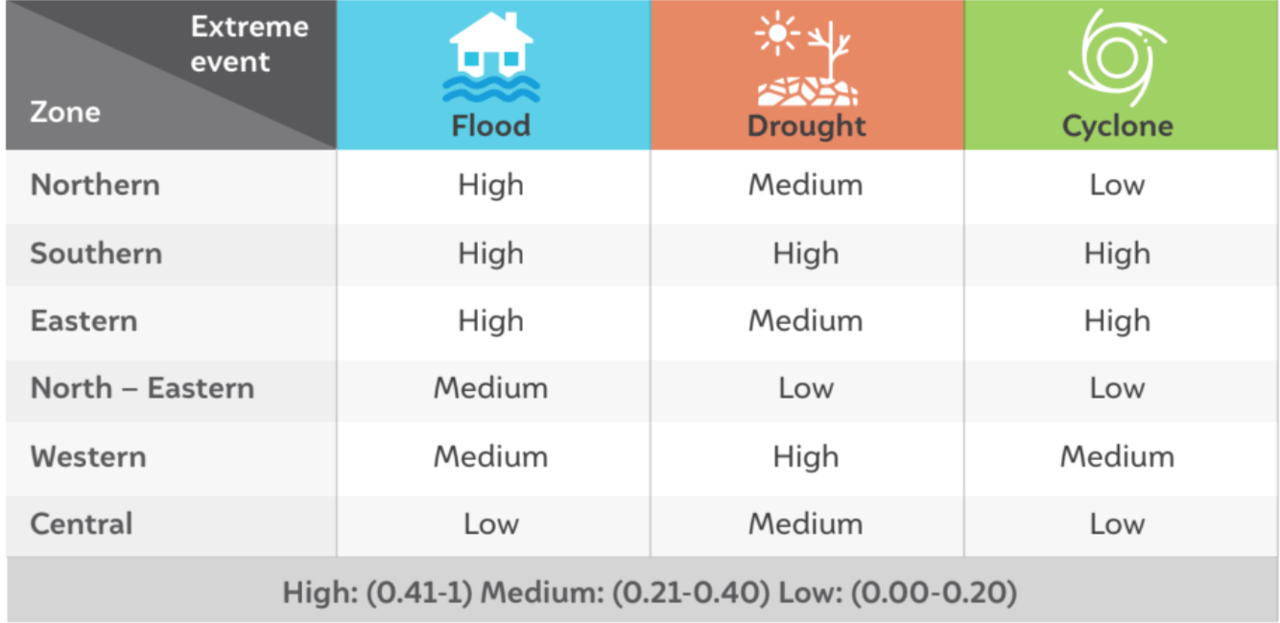

As per our analysis, 27 of 35 states and UTs are highly vulnerable to extreme hydro-met disasters and their compounded impacts (Figure below). Our analysis suggests that India’s western and central zones are more vulnerable to drought-like conditions and their compounding impacts. The northern and north-eastern zones are more vulnerable to extreme flood events and their compounding impacts. Meanwhile, India’s eastern and southern zones are highly vulnerable to extreme cyclonic events and their impacts. The eastern and southern zones are also becoming extremely prone to cyclones, floods, and droughts combined.

We find that the southern and western regions are the most vulnerable to extreme droughts and are affected year on year. These regions are predominantly affected by agricultural droughts. Since the 2000s, the northern, eastern, and central zones have been moderately vulnerable and are predominantly affected by meteorological and agricultural droughts. The north-eastern region is least vulnerable to extreme drought events.

Our composite indexing suggests that more than 59 per cent of districts located in the eastern zone are highly vulnerable to extreme cyclone events. In the western zone, more than 41 per cent of districts are cyclone hotspots. Our analysis shows that the western coast has become increasingly vulnerable to cyclones in the last decade (2010–2019). India’s northern and north-eastern zones face very few extreme cyclone events and are therefore less vulnerable. The central zone is the only zone in India with no hotspots for extreme cyclone events.

Increased drought-like conditions across India trigger the cyclogenesis process by which depressions turn into deep depressions, and deep depressions into cyclonic storms across the rapidly warming Indian Ocean. Since these cyclones are accompanied by floods, several districts across the eastern and western coasts are vulnerable to all three extremes. This makes mitigation and adaptation in these regions a daunting task. Table below enumerates zone-wise vulnerability to extreme hydro-met disasters.

Southern-zone is the most vulnerable to all three hydro-met disasters

Source: Authors’ analysis

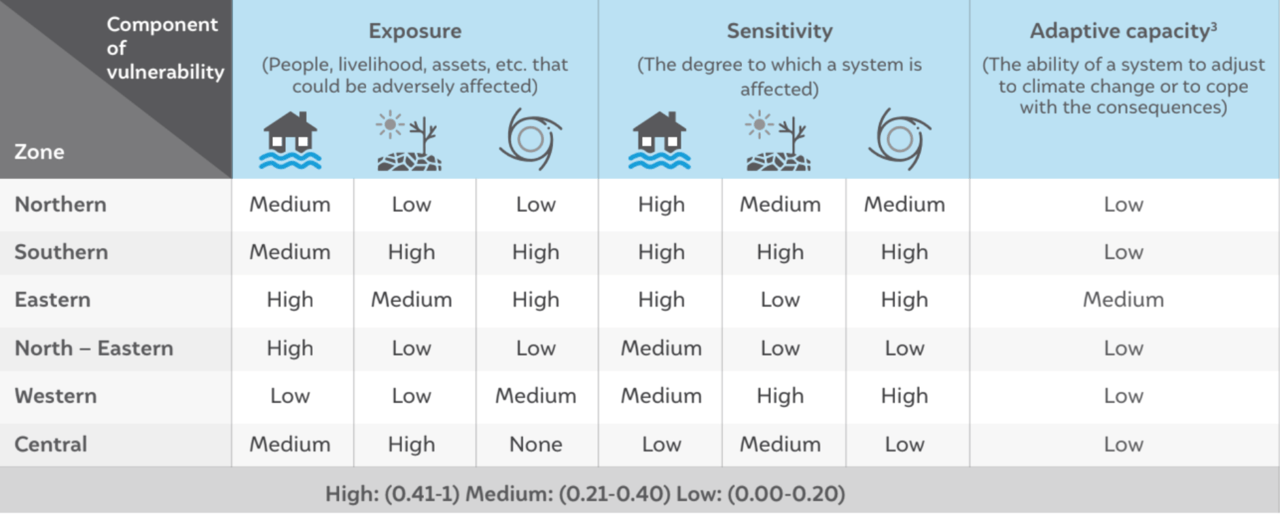

A surge in extreme events has been observed across India after 2005. Our sensitivity analysis shows that this is primarily triggered by landscape disruptions. Various studies have confirmed the impact of landscape changes on the incidence of extreme events (UNEP 2009). Other factors, such as the urban heat island effect, land subsidence, and microclimate changes, are also triggering the intensification of extreme events in India. Table below shows how individual regions are affected by each component of vulnerability.

North-eastern and eastern zones of India are highly exposed to extreme flood events

In an increasingly volatile climate landscape, hyper-local strategies can minimise impacts and avert or reduce loss and damage. The CVI intends to evaluate the vulnerability of Indian districts in a comparable unified matrix and identify the major landscape and socio-economic drivers of vulnerability. This will enable communities to map, plan and adapt against the climate extremes.

With less than a decade left to step up climate actions, our policies need a razor-sharp focus to curtail the compounded impacts of climate extremes. Principles of risk assessment should be at the core of India’s climate risk mitigation strategy. Identifying risk is the first and foremost step to building climate-proofed economies and societies that embrace climate-resilient pathways. Based on our analysis, we make the following recommendations:

1. Develop a high-resolution Climate Risk Atlas (CRA) to map critical vulnerabilities at the district level and better identify, assess, and project chronic and acute risks such as extreme climate events, heat and water stress, crop loss, vector-borne diseases and biodiversity collapse. A CRA can also support coastal monitoring and forecasting, which are indispensable given the rapid intensification of cyclones and other extreme events.

2. Establish a centralised climate-risk commission to coordinate the environmental de-risking mission (Ghosh 2021).

3. Undertake climate-sensitivity-led landscape restoration focused on rehabilitating, restoring, and reintegrating natural ecosystems as part of the developmental process.

4. Integrate climate risk profiling with infrastructure planning to increase adaptive capacity.

5. Provide for climate risk-interlinked adaptation financing by creating innovative CVI-based financing instruments that integrate climate risks for an effective risk transfer mechanism.

India urgently needs national and sub-national strategies to climate-proof its population and economic growth. If a 1.5°C warmer future climate is inevitable, we must brace for its impacts and ensure that we have the means to build back better and faster when disaster strikes. If we fail, we could set our development story back by decades.

Heat Action Plan for Thane City 2024

Policy Study on Re-calibrating Institutions for Climate Action

Decoding India’s Changing Monsoon Patterns

Strengthening India’s Disaster Preparedness with Technology