Suggested Citation: Selna Saji, Neeraj Kuldeep, and Akanksha Tyagi. 2019. A Second Wind for India’s Wind Energy Sector: Pathways to achieve 60 GW. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

This report discusses the issues that impede the development of wind energy in India and undertakes a systematic analysis to propose pathways and interventions to achieve the national target.

Wind energy is India’s oldest and best developed renewable energy technology, and needs to achieve a national target of 60 GW of installed capacity by 2022. However, factors such as frequent policy changes, infrastructural unpreparedness, and a lack of consensus among stakeholders have crippled the growth of the sector, thereby jeopardising the possibility of achieving these targets in time.

This report presents the current state of the sector in terms of capacity additions and lists policy changes and other factors that have led to the current scenario. It incorporates a detailed assessment of different approaches to achieve the national target. The report also provides various state-specific scenarios and compares them on multiple grounds, highlight the associated challenges for each. It proposes some optimum approaches to achieve the 2022 target.

Impediments to growth

Source: Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE)

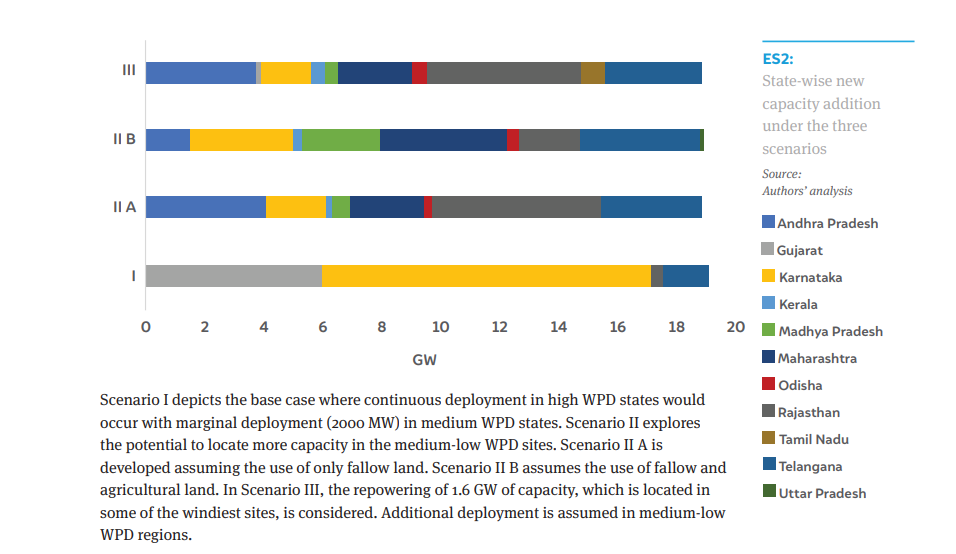

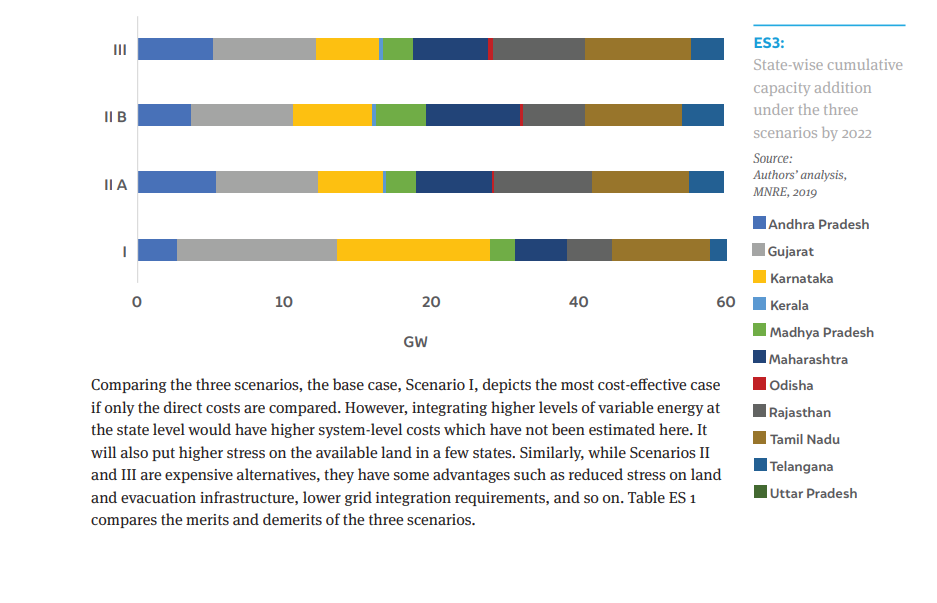

This report provides three case scenarios to achieve the 60 GW target by 2022:

Scenario 1: Base Case

Scenario 2: Low-medium Wind Power Density (WPD) sites

Scenario 3: Repowering of old power plants

Source: Authors’ analysis

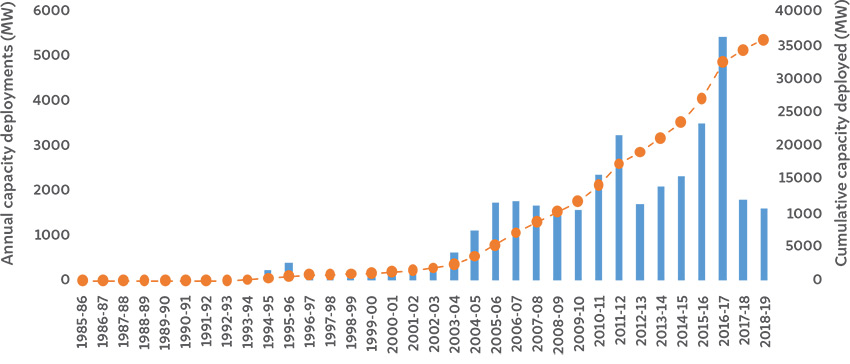

Wind energy contributes 60 gigawatts (GW) to India’s target of achieving 175 GW of renewable energy by 2022.1 However, in the last few years, the sector has witnessed an immense slowdown. The annual capacity addition of wind energy was below 2 GW for the last two consecutive years—a drastic 60 per cent decrease from the financial year 2016–17.2 Frequent policy changes, infrastructural unpreparedness, and a lack of consensus among stakeholders have crippled the growth of the sector, thereby jeopardising the possibility of achieving national targets in time.

In order to revitalise the sector and achieve the 60 GW target by 2022, this study examines the wind energy sector—its evolution over three decades and current challenges—and develops three scenarios that illustrate different pathways to achieve the minimum capacity required to reach 60 GW goal by 2022.

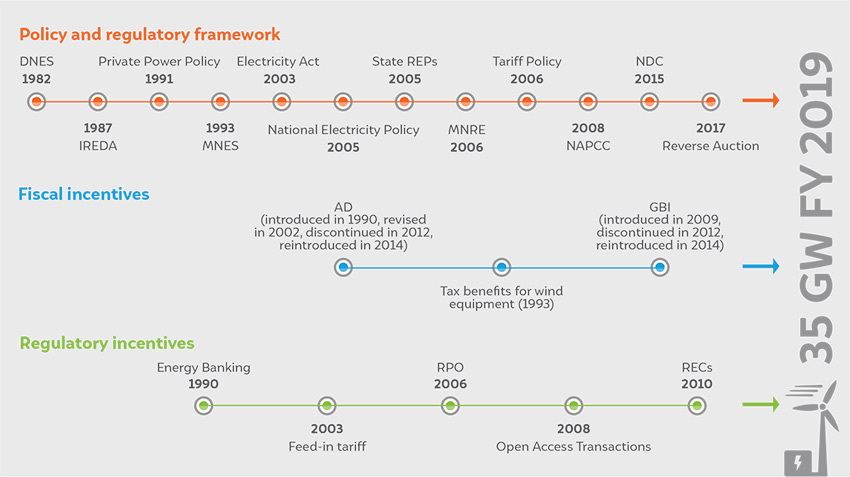

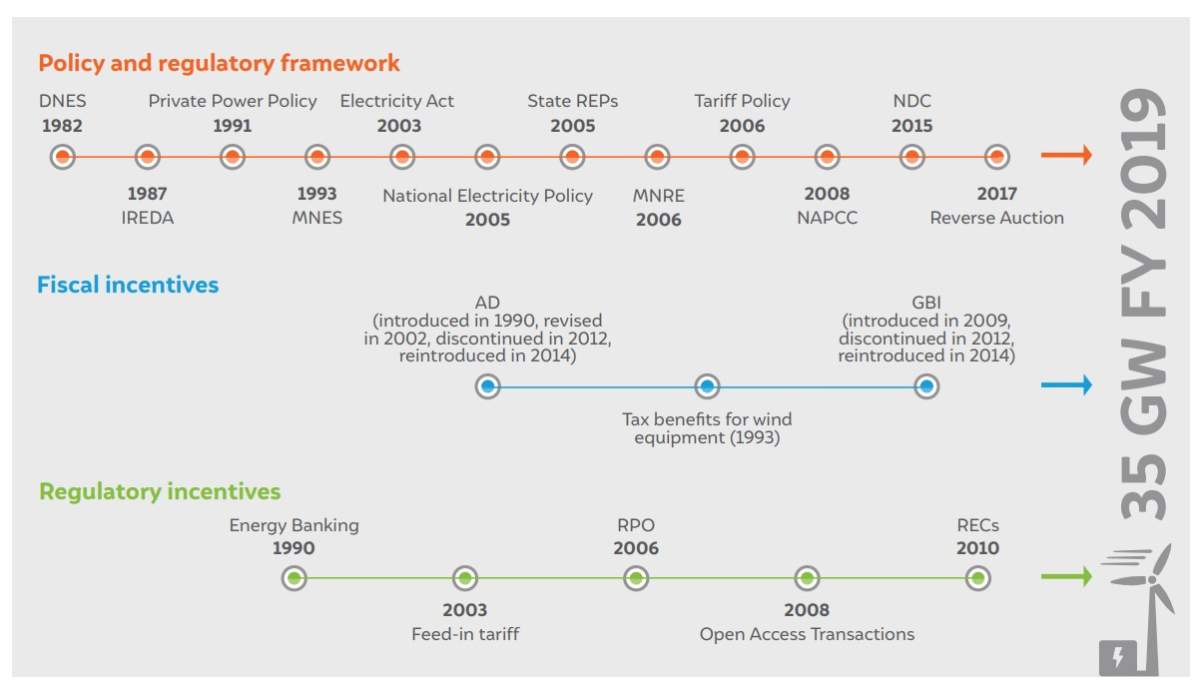

Over the last three decades, the wind energy sector has grown steadily to achieve a cumulative capacity of 35 GW,3 making India the fourth-largest market globally. The first development in the sector dates back to the 1983, when a detailed wind resource assessment was conducted by the Indian Institute of Tropical Metrology.4 Various regulatory interventions and fiscal incentives encouraged the private sector to actively invest in the area, resulting in its rapid growth. Figure ES1 illustrates the policy and regulatory framework that has shaped the wind energy sector since 1982.

ES1: Timeline of policy interventions and incentives

Source: Authors’ analysis

One of the major milestones for the sector was the transition to reverse auction from the feedin-tariff (FiT) regime. This transition also revealed some of the systemic issues that the sector faces, which were exacerbated under the new market design and have led to low annual capacity addition.

Wind resources in India are concentrated in the southern and western parts of the country, with the highest wind speeds being recorded in just three states. As reverse auction became the norm, the low ceiling tariffs set for the auctions led developers to set up plants in the windiest states; most the developers who won the bids have been looking to set up plants in Gujarat. This has put severe pressure on the available land and evacuation infrastructure in the region, leading to project delays. Reverse auctions with unfeasible ceiling tariffs coupled with the concentration of wind resources in certain regions have resulted in the following challenges that are impeding the growth of the sector:

a) Land and evacuation infrastructure availability: With the announcement of several solar and wind mega tenders, competition for suitable land with high wind speeds and grid connectivity has grown intense, making land acquisition in a timely manner an arduous task for developers. Most of the land in the high wind regions with access to grid connections have been used up. Hence, augmenting existing substations or building new ones is essential to setting up new wind power plants, which would further delay the commissioning of plants.

b) Transmission infrastructure availability: During the Twelfth Five-Year Plan period (2012–17), India’s power generation capacity grew by 91 per cent whereas its transmission capacity (lines) increased by only 43 per cent.5 There is a need to rapidly expand the transmission network to keep up with the deployment of new capacity. Additionally, most of the windy sites are located in remote locations, far from demand centres. An adequate transmission network will ensure effective evacuation of the energy generated by wind power plants, minimising curtailment.

c) Mechanism for regional cooperation: One major reason for the simultaneous creation of power surplus and power-deficit regions is the lack of an effective mechanism for regional cooperation that would enable the seamless exchange of power. There is no effective framework that facilitates the inter-regional and inter-state exchange of electricity. Thus, wind energy is generated in concentrated regions without robust markets or regulatory mechanisms to transfer the power to power-deficit regions; this can lead to surplus wind energy in concentrated regions and hamper the demand for wind power from distribution companies (discoms) in the region.

d) Discom financial health: The poor financial condition of discoms has resulted in payments to wind power producers being delayed, thus creating cash flow problems for power producers which are at risk of being classified as non-performing assets (NPAs). The delays vary between 12–24 months between states, with most renewable energy (RE)-rich states having overdue bills from over 600 days.6

e) Market design: transition to reverse bidding: Wind power developers are facing serious challenges in implementing the reverse auction process. The low ceiling tariffs (below INR 2.85/kWh) set for the auctions are not feasible and can only be achieved at the highest wind speeds. Developers are facing delays in procuring land and gaining connectivity to the inter-state transmission system (ISTS) network—all within the same region—which is putting stress on the land and connectivity in the region.

There are two approaches to address the problem of concentrated wind energy resources. The first option is to have the generation plants concentrated in wind-rich or high wind power density (WPD) regions and have robust physical and market regulatory mechanisms to enable the effective transfer of the energy generated. The second option is to distribute the capacity from high to medium and low wind power density (WPD) regions. Repowering old wind plants is another potential approach to increase the overall capacity.

This study aims to conduct a preliminary assessment of the different approaches by developing three short-term state-wise scenarios and comparing them based on multiple aspects. The scenarios developed represent three pathways aimed at achieving the 60 GW target by 2022. They are termed as follows:

I. Base case scenario

II A. Medium-low WPD sites – fallow land only

II B. Medium-low WPD sites – fallow and agricultural land

III. Medium-low WPD sites – with repowering of old power plants

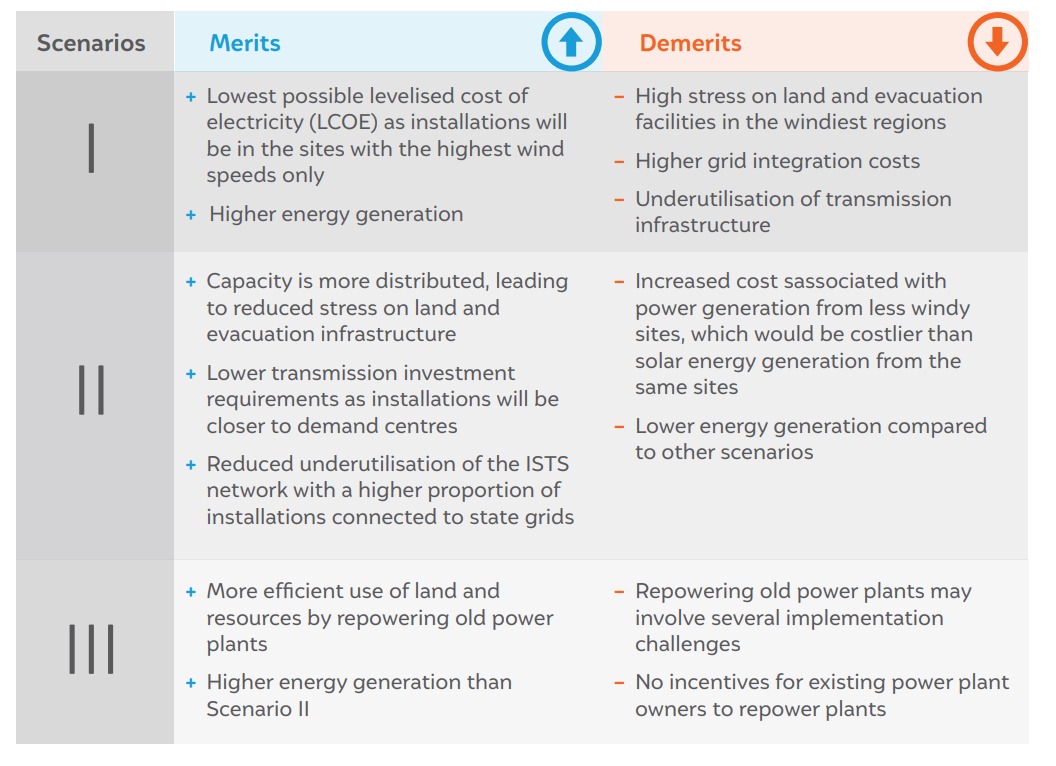

TABLE ES1: Comparison of merits and demerits of scenarios

Source: Authors’ analysis

A comprehensive policy roadmap is needed for the timely revival of the wind energy sector. A clear policy objective backed by a robust policy framework to support the new capacity addition as well as address sectoral challenges is required to revive the wind energy sector. Some key policy approaches that can increase capacity deployment in the sector in the short term are summarised below:

1. Define a clear policy objective after carefully choosing from the multiple approaches available to deploy new capacity

2. Streamline the reverse auction process to deploy new capacity at the central and state level

3. Provide regulatory support to create and sustain demand in the sector

4. Develop regulatory and financial mechanisms to address the high off-taker risk in the sector

5. Develop a regulatory framework to implement optimum grid integration practices

Enabling a Circular Economy in India’s Solar Industry

Community Solar for Advancing Power Sector Reforms and the Net-Zero Goals

Mapping India’s Residential Rooftop Solar PotentialA bottom-up assessment using primary data

Promoting the Use of LPG for Household Cooking in Developing Countries