Suggested citation: Rahman, Anas and Abhishek Jain. 2021. Can Chhatisgarh Further Equity, Prosperity, and Sustainability Through Solar Pumps? Indications from a Beneficiaries’ Survey. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

This study examines Chhattisgarh’s solar pump programme - the Saur Sujala Yojana - to understand the profiles of its beneficiaries. Understanding who is benefiting from the government support would enable informed policymaking to improve the sustainability of solar pumps. The study is based on a baseline survey of 773 beneficiaries of the scheme, which captures information on irrigation options, cropping patterns and farm income before installing the pump. The study proposes measures to ensure equitable access and just economic support for marginalised farmers and sustainable groundwater use.

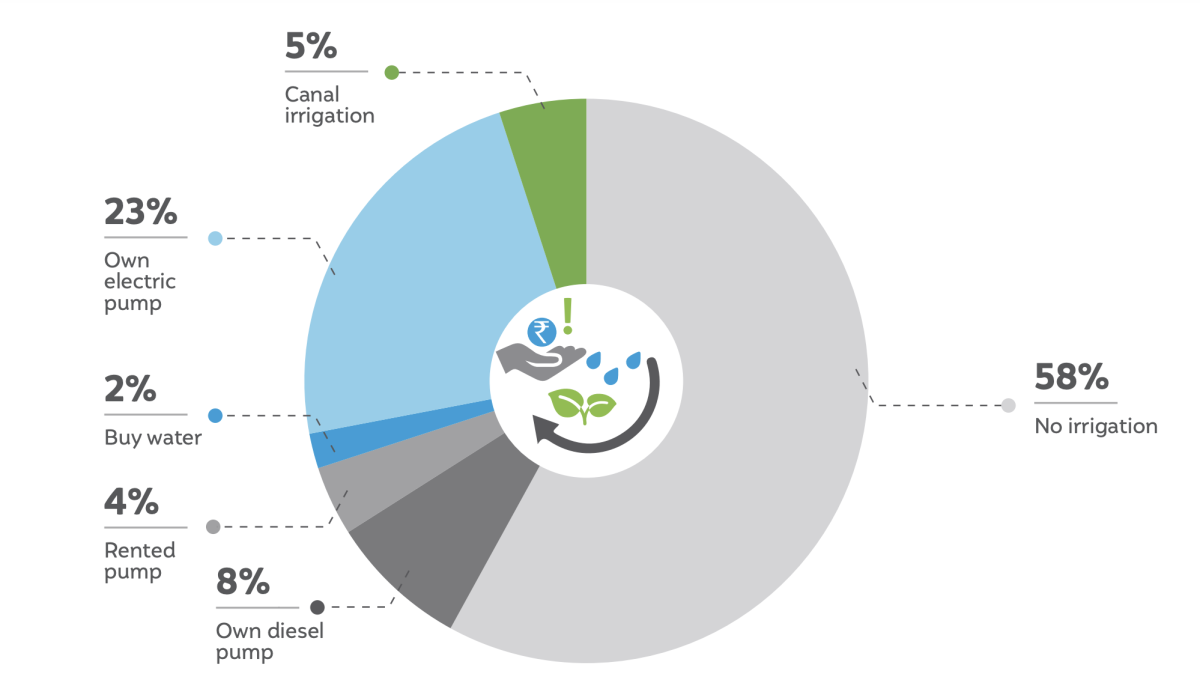

About 72 per cent of the beneficiaries targeted under SSY Phase IV currently do not have access to affordable irrigation access.

Source: Authors’ analysis of the survey data

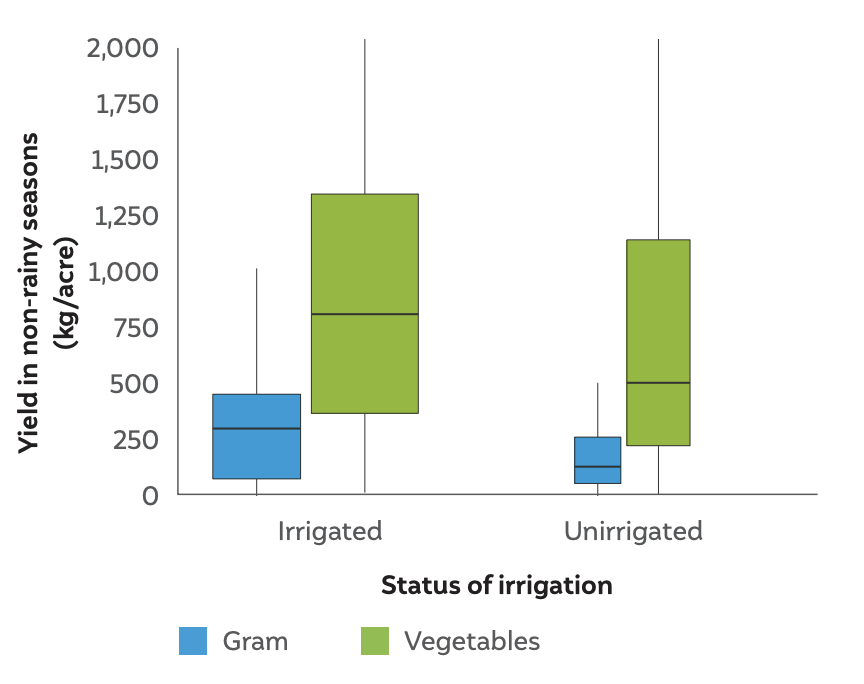

Access of irrigation has significant impact on yields of less water-intensive crop.

Source: Authors’ analysis of the survey data

Farmers in India have been increasingly adopting off-grid solar irrigation pumps over the past few years, largely due to incentives under government subsidy schemes. Beyond achieving target deployment numbers, such schemes must also ensure equitable access and economic support to irrigation for the marginalised, as well as promote sustainable use of groundwater. Different states in India have followed varied approaches to meet some of these objectives, with Chhattisgarh recording the highest number of deployments. Home to about 2.8 per cent of India’s farmers (NABARD 2016), the state boasts more than 30 per cent of India’s solar pump deployments, due to the success of the Saur Sujala Yojana (SSY) scheme. SSY provides about 90–95 per cent subsidy on solar pumps, which is available to any farmer with more than one acre of land ownership. Under SSY, more than 80,000 pumps have been installed in the last five years.

Using administrative data on all beneficiaries, and a sample survey of 773 beneficiaries of SSY’s latest phase (conducted in 2020), we present a brief analysis of the beneficiaries’ profiles, practices, and perspectives. Conducted just before the commissioning of the solar pumps, the survey provides details on farmers’ profiles, their irrigation options and incomes before the installation of the solar pumps. The insights can help various states learn from Chhattisgarh’s experience with regard to furthering social equity, economic prosperity, and environmental sustainability by promoting solar pumps.

We found that SSY has helped further irrigation access among the marginalised. As much as 58 per cent of installations were by members of Scheduled Tribe communities. This is striking given that their share in the state’s population is just 30 per cent. Two aspects of the state policy led to this success: (i) a differentiated subsidy based on social category, and (ii) geographical targeting of tribal majority areas.

The state also seems to have done reasonably well in targeting farmers without affordable irrigation option for the scheme. Prior to solar pump deployment, about 72 per cent of beneficiaries either did not have any irrigation options or depended on costly diesel pumping. However, about 23 per cent of the total allocation went to farmers with subsidised electric connections that they used to irrigate a different patch of land. We recommend that the state involve discoms in the pump allocation process to avoid this double support.

Small and marginal farmers are major beneficiaries of SSY. Ninety per cent of them cultivated less than five acres of land in the past year. However, landless farmers, or those without at least one acre of land, remain deprived. The state should consider including low-capacity mobile pumps, for such farmers. Further, only 23 out of the 773 individuals surveyed were women who owned connections, indicating that the structural bias against women in agriculture asset ownership has continued in solar pump schemes. Reserving a quota for women beneficiaries could help address this to some extent.

We assessed the potential impact of solar pumps based on the beneficiaries’ prevailing irrigation and cultivation patterns. India typically has three season of cropping. In rainfed areas, the cultivation is mostly confined to Kharif season. We found that access to irrigation is a clear determinant of cultivating in the second or Rabi season. However, summer cultivation is not prevalent even among farmers who owned a diesel or electric pump. It would be interesting to see whether solar pumps increase cropping intensity beyond two the two traditional cultivation seasons and leads to summer cultivation as well. We found that irrigation access also plays a significant role in potentially increasing crop yield for vegetables and grams, especially in non-Kharif seasons.

Consequently, targeting farmers who cultivate less water-intensive crops, such as vegetables, can help increase their economic returns. In addition to increasing cropping intensity and yield, solar pumps could also help improve farm incomes by expanding the cultivated area. The survey showed more than 63 per cent of farmers without irrigation access expected to expand their cultivated area once their solar pumps were installed.

To understand the potential utilisation of solar pumps, we looked at the current electric pump users in the sample, as they also experience zero marginal cost of operation. We found their median pump usage to be only 74 days a year. The government should promote other productive uses during non-irrigation days to improve asset utilisation. Thirty-six per cent of pump owners mentioned that they use their pumps for nonirrigation purposes. The state should capitalise on prevailing farmer behaviours to encourage the use of the asset to run other machinery such as those used for chaff cutting, grain milling, food processing, etc. Twenty-nine per cent of the beneficiaries have installed solar pumps on lands adjoining their homestead, making it easy to include such other productive uses. The study found that the cost of irrigation for diesel pumps was about INR 2,000 (USD 27) at the time of survey (Mar 2020) per acre. The cost now (Aug 2021) is likely to be 30 per cent higher, given the sharp rise in the retail price of diesel since the survey. But the cost of irrigation for electric pumps does not change significantly with an increase in the cultivated area, perhaps due to the flat rate tariff structure. At the current 90–95 per cent subsidy, the farmer’s contribution for solar pumps is about 2–6 times the average seasonal irrigation cost – indicating a payback period of fewer than three years for an asset with a potential lifespan of 20 years. We propose that there is room to reduce the state subsidy per pump in the coming years if the state could enable financing in tandem with increasing the farmer’s contribution. The cost of irrigation constitutes typically 5–15 per cent of the total input cost. This share is higher for small landholders, indicating that they will gain the most from subsidised solar pumps. This should thus be the focus of the state schemes.

Groundwater is the primary source of irrigation for most beneficiaries. Presently, the water table depth is adequate for most installations that are dependent on groundwater. But we found indications of groundwater depletion driving farmers to opt for higher capacity pumps. On average, survey respondents from districts with lower water tables reported having higher capacity pumps for the same landholding sizes. As the state contemplates increasing maximum capacity of solar pump offered under the scheme, it should be cognizant of these risks.

India is massively increasing the deployment of solar pumps for irrigation. The technology is ‘green’, but it is equally important to consider how it is being promoted and for whom. Recent literature has tried to answer the ‘how’ through comparative analyses of deployment models and case studies and pilots of various innovative approaches. However, there has been limited examination of who the beneficiaries of state-subsidised solar pumps are. Given that farmers are not a homogeneous group in India, it is important to understand beneficiaries’ profiles better, to assess whether public funds are adequately furthering equity, prosperity, and sustainability among farmers.

In this brief, we examined the solar pump programme of Chhattisgarh to understand the profiles of the beneficiaries of the state subsidy programme. Based on the findings, we recommend:

Decentralised Renewable Energy for SDG7

Decentralised Renewable Energy Technologies for Sustainable Livelihoods

Unlocking Sustainable Livelihood Opportunities for Rural Women