Integrated Pest Management system consist of using suitable techniques and methods in a compatible manner to maintain pest populations at levels below those causing economically unacceptable damage or loss." IPM combines cultural, biological and chemical measures to provide a cost-effective, environmentally sound and socially acceptable method of controlling diseases, insects, weeds and other.2 It involves the pre-season management of pests through guidance in selection of crops and cultivars suited to particular soils, timely planting, continuous monitoring of crop health and pest status, conservation practices for native natural enemies, and the use of timely and quality inputs of bio-rationals1 integrated with location-specific crop production practices.3

In principle, Integrated Pest Management adheres to and promotes most of the agroecological elements as defined by the FAO

| ELEMENTS | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Diversity | One of the crucial benefits of IPM is maintaining ecological sustainability by conserving natural enemy species, biodiversity and genetic diversity. Biological pest control is achieved by conserving and augmenting bio control agents within local environments and ensures the evolution and adaptation of beneficial insect pests, thus protecting natural habitats. |

| Co-creation and sharing of knowledge | IPM is a knowledge-intensive approach that requires a combination of compatible methods (cultural, biological, chemical, and physical). Farmers require significant knowledge in order to choose the best combination from locally available resources. IPM is a continual process of shared learning, evolving and adapting to methods both old and new for minimizing the economic, health, and environmental risks to crops and human health. |

| Synergies | IPM emphasizes using a combination of techniques and creates synergies by integrating them to use pesticides selectively. This approach requires a mindset that seeks to create synergies between traditional and novel IPM principles for plant protection solutions. |

| Efficiency | IPM is considered cost-effective and more efficient than chemical pest control since it reduces the need to apply pesticides thus lowering the production costs. Further, the synergies created when alternative options to counter pests are used in combination, may be more efficient than standalone application of these solutions. |

| Resilience | With the rise in pest incidence exacerbated by climate change, such as locust infestations observed in recent months in the country, IPM offers an approach which can adapt to these uncertainties. When applied continually and locally rather than as a short-term tactic, it can improve the resilience of cropping systems. |

| Human and social values | IPM places a strong emphasis on human and social values by building the adaptive capacity of farmers to deal with their food systems and maintain ecosystem harmony. |

‘The crop yield losses due to insect pests, diseases, nematodes, weeds and rodents range from 15-25 percent in India, amounting to 0.9 to 1.4 lakh crore rupees a year (USD 12-18.5 billion).4 Due to such deleterious effects, research into IPM was initiated in 1974-75 for two crops, rice and cotton, under multiple operational research projects supervised by several departments (Directorate of Rice Research, Hyderabad; Kerala Agricultural University; Department of Agriculture, West Bengal). However, these were location-specific interventions. It was only in the mid-1980s that the focus was redirected towards a national plant protection strategy by the Government of India.

At present, there are 35 Central Integrated Pest Management Centres (CIPMCs) established in over 28 states and 2 UTs to promote IPM in India. Under the National Mission on Agricultural Extension and Technology (NMAET-Plant Protection & Plant Quarantine), around 2.90 million hectares of pest monitoring have been completed and CIPMCs have released 59,379.72 million biocontrol agents between 1994-95 and 2019-20. At the same time, the mission has trained 574,600 farmers through farmer field schools, around 19,142 of which were organized by the CIPMCs, KVKs and SAUs. The mission supplements state programs through grants for establishing biocontrol laboratories (INR 5 million/USD 68,000 per lab for construction, equipment and facilities).5

RKVY launched by the Government of India during the XI Plan period, allows for the innovative and pervasive use of information and communication technology for reaching out to farmers to assess the pest scenario in their fields, and for issuing real-time pest management advisories through SMS.

How much area in India is under IPM? Around 3-5 percent (4.2 to 7 million hectares) of India’s total cultivated area is under IPM, according to a stakeholder consulted in the Indian Council of Agricultural Research-National Centre for Integrated Pest Management (ICAR-NCIPM), an institute that has been validating and refining IPM strategies since its inception in 1988.

At what farm size is IPM practiced? Stakeholders consulted in both ICAR-NCIPM and the Directorate of Plant Protection Quarantine & Storage (DPPQ&S) - the apex organisation for plant protection in the country observed that IPM is being practiced in irrigated and rainfed areas on all landholding types.

How many farmers in India are practicing IPM? Despite the promotion of the practice for the past three decades and its benefits, adoption of IPM remains low. The practice is adopted by only 3.2 percent (3.7 million) of farmers in country.6 Post 2010, we find that farmers are increasingly employing evolving technologies and farm practices to enhance efficiency and reduce costs, thus we expect the adopters as of present to stand at around 4-5 million of them.

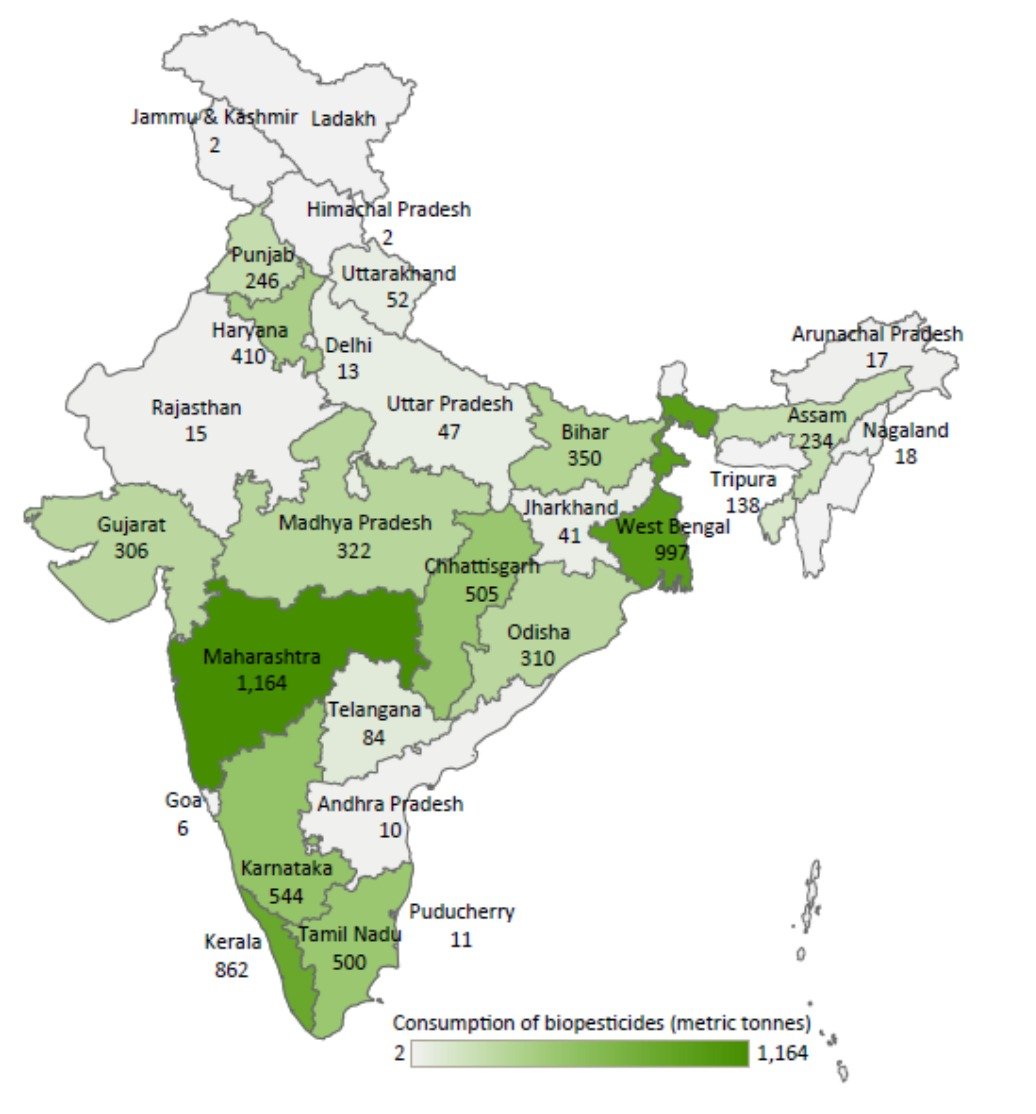

Where in India is IPM prevalent? IPM projects are implemented by ICAR-NCIPM in 22 states and 95 districts, and it is also promoted by the 35 CIPMCs across 28 states and 2 UTs through farmer field trials. However, the largest states of India — i.e., Maharashtra, West Bengal, Kerala, Karnataka — are the most advanced in implementing these practices as seen by their highest consumption of biopesticides. These states are also the main cotton-rice cultivators, crops which the IPM programs target. Since biopesticides are one of the chief ingredients used in IPM, its consumption pattern is assumed as a reliable method to understand the relative adoption of IPM in the states as shown in Figure 1.

Which are the major crops cultivated under IPM in India? In India IPM is mainly targeted at rice, cotton, pulses, oilseeds, fruit and vegetables with favorable results especially in rice, cotton and horticultural crops.

A vital aspect of IPM systems is their ‘bottom-up’ or ‘participatory approach,” as the practice is knowledge intensive, disseminated through farmer field trials to understand farmers’ perceptions, knowledge and experiences in their fields in order to give sound advice. Field validation trials are conducted by the ICAR-NCIPM for several crops (rice, cotton, pulses, oilseeds, horticultural crops) across the country, which have given important findings on crop yields, income and other parameters — soil, nutrient and fertilizer use, water, etc., as outlined in the sections below.

ECONOMIC IMPACT

IPM is perceived as a better ‘control tactic’ that results in better yields and profits for the farmer. However, in the short run there are possibilities of a yield decline when farmers first switch to IPM.7

Rice: IPM is seen as an effective way to overcome the pests and diseases in rice, which cause an average estimated yield loss of about 25 percent, though they can be as high as 51 percent with serious infestations (borer, gall midge, plant-hoppers). IPM programs are known to have prevented pest outbreaks across a wide area in rice in the last decade or so since they were implemented, thanks to policy changes and field training8 In the IPM validation trials done for rice in various states (Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Uttarakhand), there are strong indicators of IPM benefits for farmers as the incidence of insect pests and diseases have remained low, and yield and benefit-cost ratios have remained higher in IPM compared to farmers’ previous practices.9

Cotton, a key cash crop, faces substantial yield reductions due to pests, accounting for 50-60 percent of losses. An assessment looked at the impacts of IPM in the rainfed cotton belt of Maharashtra. It recorded an average seed cotton yield of 962.5 kgs/hectare compared to 220 kgs/hectare during the previous season, reflecting an increase of 77.1 percent.10 Experiments by DPPQ&S also show crop yield increases for rice (from 6.72 to 40.14 percent) and cotton (from 22.7 to 26.63 percent) in IPM fields compared to nonIPM fields.11

‘The implementation of IPM has led to increased pulse production of 15-20 percent due to reduction of pest incidences and intensity (in central and southern India) among crops (pigeonpea, chickpea, mung and black gram, lentil). Among horticultural crops (bitter gourd, cucumber, bottle gourd, onion, and bell pepper) where IPM was validated, yield gains were observed along with reduced use of chemical pesticide sprays.12

IPM offers great scope for farmers to increase their income by reducing the severity of pest infestations in crops, while also lowering the problems of pest resistance or resurgence.

Evidence across the papers suggests that IPM is likely to decrease the cost of production due to the reduced number of pesticide applications required, given the cost of active ingredients and pesticides in several crops (rice, cotton, pulses). Coupled with the increases in yield, IPM is said to offer a higher net income per hectare and higher benefit-cost ratio than conventional practices. Over the years IPM used in Basmati rice is observed to drastically cut input costs through reduced use of pesticides, fertilizers and irrigation. Farmers are able to secure a residue-free product with a higher cost-benefit ratio (ICAR-NRRI stakeholders).

According to researchers in NCIPM, IPM technology not only increases yields by 20 percent (on average) compared to conventional farming methods, it also reduces the costs of production by around 10 percent (on average) across all crops due to the reduction in the quantity of chemical pesticides sprayed. This is substantiated through studies by the DPPQ&S that show IPM to reduce chemical pesticide sprays by 50- 100 percent in rice and 29.96-50.5 percent in cotton, implying significant savings for farmers.13

Another study found that in vegetables like cauliflower, the costs of production, including for plant protection, were less in IPM fields than for farmers using chemical pesticides. Economic analysis of the data also showed higher economic returns and cost-benefit ratios for IPM practices (4.79) compared to conventional practices (3.26). The higher benefits were primarily due to the decrease in input costs for plant protection in TPM fields.14 Hence, much of the evidence suggests that TPM can enhance farmers’ income across several crops and regions.

SOCIAL IMPACT

One of the tangible benefits arising from IPM is the improved environment and human health due to reduced use of chemical pesticides. IPM prescribes the use of chemical pesticides only as the last resort when all other methods fail; chemicals are chosen judiciously to reduce human health hazards.15 Though there is a considerable literature that mentions the health benefits of IPM, there are no systematic studies and field experiments that delve deeper into the topic.16,17 However, one study indicates that the application of pesticides including its supply chain processes involves greater health hazards than the safer inputs used in IPM.18

Overall consumption of chemical pesticides reduced from 61,357 MT (Tech. grade) in 1994-95 to 49,438 MT in 2018-19.

There is limited work done on the impact of IPM practices on women; a few case studies show the role of women in participating and disseminating IPM practices.

In Ashta village in the rainfed cotton belt of Maharashtra, the participation of women was found to speed up dissemination of IPM technology in cotton.19 Women were also observed to play an important role as ambassadors spreading awareness about IPM in cotton in Jind, Haryana. They motivated and imparted training to farmers to identify “friend” and “enemy” insects and avoid use of chemical pesticides to deal with whitefly attack in cotton.20

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS

IPM focuses on adopting a variety of agronomic measures that avoid or reduce pest infestations; soil and nutrient management forms an integral part of the approach. For example, IPM emphasizes the incorporation of green manures, balanced use of fertilizers, regular crop and pest monitoring, conserving natural pest enemies, use of bio-pesticides and reduced application of chemical pesticides, and cultural control methods, all of which have implications for soil health. According to a stakeholder, local organic solutions such as Neemastra, Panch Gawye, JivaAmrit, BijaAmrit, Amrit Pani, Amrit mitti, Brahmastra are also very popular in the IPM management along with various pheromone traps.

Cultural control methods tend to prevent soil-borne diseases which can inflict damage on crops. For instance, treating soils (mowing, fertilizing, pruning, mulching, and irrigating) and deep ploughing are known to kill various pests; ploughing is an important control measure to expose the soil-inhabiting stages of several vegetable pests. As too high or too low nitrogen content in plants can also lead to disease problems, testing of soil for nutrient deficiencies is very important to maintain the appropriate amount of fertilisers used. Crop rotation is also encouraged to reduce the build-up of soil-borne diseases, while avoiding high moisture levels for prolonged periods also helps reduce pests, especially soil-borne diseases. Mechanical controls involving weed management is very important as weeds compete with crops for micronutrients as well as harbouring pests.21

‘Water is an important part of cultural control, as alternate wetting and drying is required to avoid stagnancy in endemic areas infested with plant hopper, bacterial blight and stem rot in paddy fields. As insect pests like Whorl maggot are attracted to standing water, draining of the water at intervals (every 3- 4 days) reduces their chances of laying eggs.22

IPM practices are known to have better outcomes for surface and groundwater quality with reduced contamination from pesticides.23 An investigation conducted in the integrated watershed program in ‘Telangana, in which biointensive pest management methods were applied for three consecutive years. The fields where IPM was applied had lower pesticide residues; however, an initial water analysis indicated residues to be higher in borewells than in open wells. But, by the third year, water bodies contained no detectable residues, indicating contamination is lowered in IPM fields over time.24

Energy does not find much relevance in IPM. It is likely that biopesticides require less energy to manufacture than chemical pesticides. Biopesticides are pesticides derived from animals, plants (neem, tobacco) microorganisms (bacteria, virus, fungus, nematodes) and certain minerals (canola oil and baking soda). Botanical pesticides are manufactured from different parts of plants with insecticidal properties and energy is required for the extraction of the chemicals. Bulk quantity is required in the production process and thus trees like neem have to be planted many years in advance. Different microorganisms are mass cultured artificially in the process of manufacturing microbial pesticides which also requires energy. Energy is also used for powering insect light traps for catching agricultural pests like moths, hoppers, beetles, etc. As these light traps are operated by various means — electricity, battery, solar energy, generators — they can contribute to energy consumption.25 But this area requires more research, especially studies comparing energy use for chemical insecticides and biopesticides.

We found no publications correlating the IPM system to carbon emissions in the Indian context, highlighting a notable research gap.

IPM conserves biodiversity by encouraging the natural enemies of pests. However, no systematic studies on the impact of IPM on biodiversity were found in India. One study on the impact of IPM on soil inhabiting natural enemies implies that treating plants with bio-pesticides (Helicoverpa Nucleo Polyhedrosis virus-HNPV)? showed minimum disturbance to natural enemies compared to those treated with endosulfan.26

State of available research discussing the impact of conservation farming on various outcomes.

|

Evidence type |

Yield |

Income |

Health |

Gender |

Soil & nutrients |

Water |

Energy |

GHG emissions |

Bio-diversity |

|

Journals |

12 |

11 |

5 |

0 |

5 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Reports |

2 |

2 |

6 |

1 |

5 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

Articles/case-studies |

0 |

3 |

2 |

0 |

8 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Others** |

13 |

0 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Total |

27 |

16 |

20 |

1 |

18 |

16 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

** Thesis, guidelines, conference papers, etc Source: Authors' compilation

Note — The evidence is from the first 75 results examined in Google Scholar Advanced search and the first 30 results from Google Advanced Search. Only those papers which clearly established the evidence for different indicators were selected.

The following institutions are involved in the research and promotion of conservation farming; a few were consulted for this research:

|

Government institutions |

Research/implementation institutions |

NGOs/Civil society organisations |

|

Directorate of Plant Protection Quarantine & Storage |

Marathwada Agricultural University, Parbhani |

PRADAN |

|

ICAR-National Research Centre for Integrated Pest Management |

ICRISAT |

Gram Disha Trust |

|

National Institute of Plant Health Management |

BAIF Development Research |

CARITAS INDIA |

|

Department of Agriculture, Co-Operation & Farmers Welfare |

M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation |

People's Science Institute |

|

Indian Institute of Chemical Technology, Hyderabad |

Anand Agricultural University, Anand |

Samaj Pragati Sahayog |

|

Central Institute of Cotton Research, Nagpur—India |

Jamnalal Kaniram Bajaj Trust |

Source: Authors' compilation

Note — The stakeholders list is indicative and not exhaustive

1 Anand Prakash, ] S Bentur, M Srinivas Prasad, R K Tanwar, O P Sharma, Someshwar Bhagat, Mukesh Sehgal, et al. 2014. “Integrated Pest Management Package for Rice.” Crop Protection. Faridabad. https://ppqs.gov.in/sites/default/files/rice.pdf

2 Directorate of Plant Protection Quarantine & Storage. 2019. “IPM at A Glance.” https://ppqs.gov.in/divisions/integrated-best-management/ibm-glance

3 Vennila, S, Birah Ajanta, Kanwar Vikas, and C. Chartopadhyay. 2016. Success Stories of Integrated Pest Management in India. Edited by. Vennila, Birah Ajanta, Kanwar Vikas, and C. Chattopadhyay. ICAR-National Research Centre for Integrated Pest Management. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3070.6326.

4 Palghar, Thane, S Vennila, Ramchandra Lokare, Niranjan Singh, Subhash M Ghadge, and C Chattopadhyay. 2016. “Crop Pest Surveillance and Advisory Project of Maharashtra A Role Model for an E-Pest Surveillance and Area Wide Implementation of Integrated Pest Management in India.” Pune. www.ncipm.org.in.

5 Directorate of Plant Protection Quarantine & Storage. 2019. “IPM at A Glance.” http://ppqs.gov.in/divisions/integrated- pest-management/ipm-glance.

6 Rao, G V Ranga, and V Rameswar Rao. 2010. “Status of IPM in Indian Agriculture: A Need for Better Adoption.” Indian Journal of Plant Protection 38 (2): 115-21.

7 Sehgal, Mukesh, Meenakshi Malik, R V Singh, A K Kanojia, and Avinash Singode. 2018. “Integrated Pest Management in Rice and Its Future Scope.” Int.J. Curr- Microbiol. App.Sci 7 (6): 2504-11. doi:10.20546/ijcmas.2018.706.297.

8 Ibid

9 Indian Council of Agricultural Research - National Centre for Integrated Pest Management. 2020a. “Achievements (2014- 20).” https://www.ncipm.res.in/achievements.

10 Directorate of Plant Protection Quarantine & Storage. 2020b. “Integrated Pest Management in Coton.” https:/fwww.ncipm.res.in/NCIPMPDFs/successstories/COTTON.pdf.

11 Directorate of Plant Protection Quarantine & Storage. 2019. “IPM at A Glance.” https://ppqs.gov.in/divisions/integrated-pest-management/ipm-glance

12 Indian Council of Agricultural Research - National Centre for Integrated Pest Management. 2020a. “Achievements (2014- 20).” https://www.ncipm.res.in/achievements.

13 Directorate of Plant Protection Quarantine & Storage. 2019. “IPM at A Glance.” https://ppqs.gov.in/divisions/integrated-pest-management/ipm-glance

14 Vennila, S., Birah Ajanta, Kanwar Vikas, and C. Chattopadhyay. 2016. Success Stories of Integrated Pest Management in India. Edited by S. Vennila, Birah Ajanta, Kanwar Vikas, and C. Chattopadhyay. ICAR=Narional Research Center for Integrated Pest Management. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3070.6326.

15 Ibid

16 Directorate of Plant Protection Quarantine & Storage. 2014, “Standard Operating Procedures for Integrated Pest Management.” Faridabad.

17 Singh, Archana U, and Prasad D. 2016. “Integrated Pest Management with Reference to INM.” Advances in Crop Science and Technology 04 (03): 3-7. doi:10.4172/2329-8863.1000220.

18 Jindal, Vikas, G S Dhaliwal, and Opender Koul. 2013. “Pest Management in 21st Century: Roadmap for Future.” Biopesticides International 9 (1): 1-22. http://www.connectjournals.com/file_full_text/1754001H_1-22.pdf.

19 Vennila, S., Birah Ajanta, Kanwar Vikas, and C. Chattopadhyay. 2016. Success Stories of Integrated Pest Management in India. Edited by S. Vennila, Birah Ajanta, Kanwar Vikas, and C. Chattopadhyay. ICAR-National Research Centre for Integrated Pest Management. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3070.6326.

20 Ibid

21 Kaur, Tamanreet, and Mandeep Kaur. 2020. “Integrated Pest Management: A Paradigm for Modern Age.” In Pests - Classification, Management and Practical Approaches [Working Tide]. Jalandlar: InwechOpe. doi:10.5772/intechopen.92283.

22 Anand Prakash, J S Bentur, M Srinivas Prasad, R K Tanwar, O P Sharma, Someshwar Bhagat, Mukesh Sehgal, et al. 2014. “Integrated Pest Management Package for Rice.” Crop Protection. Faridabad. http://ppgs.gov.in/sites/default/files/rice.pdf.

23 Singh, Archana U, and Prasad D. 2016. “Integrated Pest Management with Reference to INM.” Advances in Crop Science and Technology 04 (03): 3—7. doi:10.4172/2329-8863.1000220.

24 Rao, G V Ranga, B Ratna Kumari, K L Sahrawat, and S P Wani. 2015. “Integrated Pest Management (IPM) for Reducing Pesticide Residues in Crops and Natural Resources.” In New Horizons in Insect Science: Towards Sustainable Pest ‘Management, edited by A. K. Chakravarthy (ed.), 397-412. Patancheru: Springer India. doi:10.1007/978-81-322-2089-3.

25 Vennila, S., Birah Ajanta, Kanwar Vikas, and C. Chattopadhyay. 2016. Success Stories of Integrated Pest Management in India. Edited by S. Vennila, Birah Ajanta, Kanwar Vikas, and C. Chattopadhyay. ICAR-National Research Centre for Integrated Pest Management. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3070.6326.

26 Rao, G V Ranga, B Rarna Kumari, K 1. Sahrawar, and S P Wani. 2015. “Integrated Pest Management (IPM) for Reducing Pesticide Residues in Crops and Natural Resources.” In New Horizons in Insect Science: Towards Sustainable Pest ‘Management, edited by A. K. Chakravarthy (ed.), 397—412. Patancheru: Springer India. doi:10.1007/978-81-322-2089-3.

Suggested citation: Gupta, Niti, Shanal Pradhan, Abhishek Jain, and Nayha Parel. 2021. Sustainable Agriculture in India 2021: What We Know and How to Scale Up. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water

The Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) is one of Asia’s leading not-for-profit policy research institutions. "The Council uses dara, integrated analysis, and strategic outreach to explain — and change — the use, reuse, and misuse of resources. It prides itself on the independence of its high-quality research, develops partnerships with public and private institutions, and engages with wider public. In 2021, CEEW once again featured extensively across ten categories in the 2020 Global Go To Think Tank Index Report. The Council has also been consistently ranked among the world’s top climate change think tanks. Follow us on Twitter @ CEEWIndia for the latest updates.

FOLU Coalition: Established in 2017, the Food and Land Use Coalition (FOLU) is a community of organizations and individuals committed to the urgent need to transform the way food is produced and consumed and use the land for people, nature, and climate. It supports science-based solutions and helps build a shared understanding of the challenges and opportunities to unlock collective, ambitious action. The Coalition builds on the work of the Food, Agriculture, Biodiversity, Land Use and Energy (FABLE) Consortium teams which operate in more than 20 countries. In India, the work of FOLU is being spearheaded by a core group of five organizations: Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad (IIMA), The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI), Revitalising Rainfed Agriculture Network (RRAN) and WRI India.

Contact [email protected]/ [email protected] for queries