Organic farming is a production system that prohibits the use of synthetically produced agro-inputs (fertilizers and pesticides). Instead, it relies on organic material (such as crop residues, animal residues, legumes, bio-pesticides) for “maintaining soil productivity and fertility and managing pests under conditions of sustainable natural resources and a healthy environment.”1

Eliminating synthetic or chemical-based inputs is, however, only one aspect of the organic production system. More importantly, it emphasizes a whole-system approach in which all the individual components (soil minerals, organic matter, micro-organisms, insects, plants, animals, and humans) create a sustainable and self-regulating ecosystem. The National Organic Standards Board of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) defines it as "an ecological production management system that promotes and enhances biodiversity, biological cycles, and soil biological activity. It is based on the minimal use of off-farm inputs and management practices that restore and enhance ecological harmony."2

As a system, it entails several components with specific and integrated functions. The use of cover crops, green manures, animal manures, crop rotations, mixed farming, organic manure, and compost is encouraged to improve soil fertility, maximize biological activity, and maintain long-term soil health. Similarly, weeds are managed by using crop rotations, good crop husbandry, and biological controls. Pests and diseases are managed using diversity, bio-intensive pest management, and other biological controls. Finally, it emphasizes reducing external off-farm inputs and focusing on conserving the biodiversity of the agricultural system and the surrounding environment.’3

In principle, Organic Farming adheres to and promotes most of the agroecological elements as defined by the FAO

| ELEMENTS | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Diversity | The use of intercropping, mixed cropping and crop rotations in organic farming combines various complementary species to increase the field's spatial and temporal diversity |

| Co-creation and sharing of knowledge | Organic farming is a knowledge-intensive method of agricultural production. While methods and practices guide its implementation, its viability depends on the local and regional context. In India, organic farming started as a grassroots movement by farmers and civil society organizations. It has evolved by combining farmers’ traditional local knowledge with more scientific know-how of scientists and researchers. |

| Synergies | Apart from the biological synergies created by the interaction of various elements under organic farming, as a whole farm system, it also encourages the use of locally available resources, emphasizing resilience and reducing input costs, enabling synergies with social-ecological systems. |

| Efficiency | The efficiency of resource use is critical in organic farming. Synthetic agro-inputs are substituted by green manures, organic manures, compost, waste materials such as oil cakes, and biological controls. |

| Recycling | Composting and the use of green manures are elemental in organic farming. It aims for no waste to be produced, as any by-product, usually termed waste, is recycled into other parts of the farm. Generally, compost is made from animal manure, fresh green leaves, and carbon rice materials such as paddy straw, wood chips, and dry leaves. |

| Resilience | The premium price from organic products and the extra income from diversifying crops help build households’ socioeconomic resilience. Similarly, by reducing dependence on external inputs, farmers’ costs decrease, and they are likely to be less vulnerable to economic risks. Newer market opportunities are created by producing certified products, which helps raise household incomes. |

| Human and social values | Organic farming is a knowledge-intensive method of agricultural production. While methods and practices guide its implementation, its viability depends on the local and regional context. In India, organic farming started as a grassroots movement by farmers and civil society organizations. It has evolved by combining farmers’ traditional local knowledge with more scientific know-how of scientists and researchers. |

Farmers and enterprises adopt organic agriculture in India for different reasons. In the low rainfall areas, which tend to be no- or low-input zones, it has always been the traditional practice (maybe because of the lack of resources for conventional agriculture). The majority of such farmers are uncertified, despite pursuing organic practices. In other cases, farmers have adopted organic farming, having realized conventional agriculture's ill effects (low soil fertility, food toxicity, increased input costs). This category includes both certified and uncertified farmers. A third group comprises farmers and enterprises that have systematically adopted commercial organic agriculture to benefit from the premium price for certified organic produce.4

The Government of India has been promoting organic farming in the country through two dedicated national schemes: Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana (PKVY) and Mission Organic Value Chain Development for North East Regions (MOVCD-NER) since 2015 through state governments. Under these schemes, the support provided includes forming farmers’ clusters or farmer producer organizations; input procurement; value addition, including post-harvest infrastructure creation; packaging; branding and publicity; transportation; and organizing organic fairs.5

Organic farming is supported under other national schemes, such as Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana (RKVY), the Mission for Integrated Development of Horticulture (MIDH), and the All-India Network Programme on Organic Farming under the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR). Certification of organic farming is either done through the Participatory Guarantee System (PGS) or third-party certification by the Agriculture Processed Food and Export Development Authority (APEDA) in the Ministry of Commerce.

Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana (PKVY) is a centrally sponsored scheme launched in 2015 under the National Mission of Sustainable Agriculture (NMSA). It promotes organic farming across India through a cluster approach (500-100 ha). The scheme helps farmers obtain Participatory Guarantee System (PGS) certification. Besides, organic inputs and capacity building are provided to registered farmers. Assistance is also offered to establish vermicompost units, including vermin hatcheries, and woven beds for vermiculture.6

Mission Organic Value Chain Development for North East Regions (MOVCD-NER) is another centrally sponsored scheme launched in 2015. It is a sub-mission under the National Mission of Sustainable Agriculture (NMSA) for implementation in Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, Tripura, and Meghalaya. The scheme aims at developing certified organic production through a value chain approach to link producers with consumers and support the entire value chain development.

How much area in India is under organic farming? As of March 2020, 2,780,000 hectares were under certified organic farming in India, about 2 percent of India's 140.1 million hectares net sown area. Of this, 1,940,000 hectares were under the National Programme for Organic Production-APEDA (NPOP), 590,000 hectares under PKVY, 70,000 hectares under MOVCD-NER, and 170,000 hectares under state schemes.7

In addition to this, under the NPOP, 1,490,000 hectares are designated as wild harvest areas for medicinal plants and aromatic plants, fruits, nuts, gums, honey, and marine and aquatic plants across 21 states. The top five states with the largest certified wild harvest area (80 percent of the total area) are Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and Jammu & Kashmir.8

How many farmers in India are practicing organic farming? As of March 2020, over 1.9 million farmers in India were registered under the two certification systems: 753,319 farmers were registered on the PGS THE COUNCIL India portal, and 1,147,401 farmers were registered with third-party certification.9 There is no information available on the number of uncertified organic farmers in India.

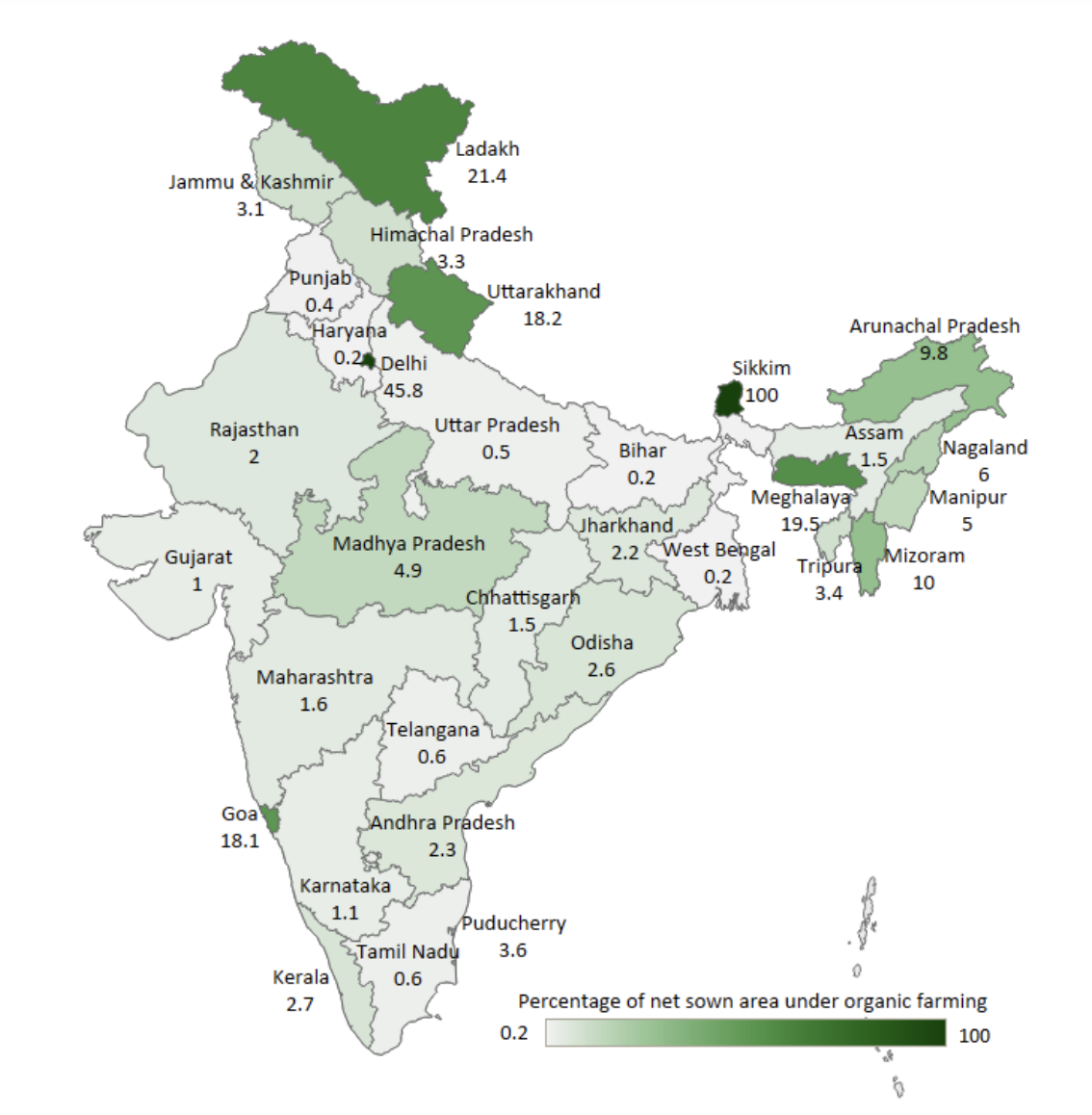

Where in India is organic farming prevalent? Organic farming is practiced across almost all states in India (Figure 1), with Sikkim formally declared a 100 percent organic state in 2016. The top three states, accounting for almost half of the area under organic cultivation, are Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Maharashtra. A recently published report by the Centre of Science and Environment highlights how only a small fraction of most states are under organic farming. The top three states that account for the largest area under organic cultivation—i.e., Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Maharashtra—have only 4.9, 2.0, and 1.6 percent of their net sown area under organic farming, respectively. Other states, such as Meghalaya, Mizoram, Uttarakhand, Goa, and Sikkim, have 10 percent or more of their net sown area under organic.10

Which are the major crops cultivated under organic farming in India? In 2019-20, India produced 2.75 million tonnes of certified organic products, including all varieties of food products — oilseeds, sugarcane, cereals and millets, cotton, pulses, aromatic and medicinal plants, tea, coffee, fruits, and vegetables, spices, dry fruits, and processed food. In terms of share of export value of processed organic foods, soya meal takes the lead (45.87 percent); followed by oilseeds (13.25 percent); plantation crop products such as tea and coffee (9.61 percent); cereals and millers (8.19 percent); spices and condiments (5.20 percent); dry fruits (4.98 percent), and medicinal plants (3.84 percent).

India as a world leader in organic cotton production

India contributed 51 percent (37,138 MT) of the global organic cotton production in 2018-19. India also had the most land under cotton in organic conversion, at 23,251 ha, followed by Pakistan (17,632 ha) and Turkey (6,148 ha).

This section considers the economic, social, and environmental impacts of organic

ECONOMIC IMPACT

The yields and net return from organic farming depend on several factors other than the production system. These include proper and scientific management of nutrient and pest management systems with multiple approaches, conversion time, market availability for premium prices, and certification. Given that it is essential to look at these other factors while evaluating yield and net return, it is not easy to generalize the overall economic impacts. Also, it is not easy to measure organic farming's contribution to food security at the country level, as only two percent of the agricultural land is under organic farming.

More than 30 peer-reviewed journal articles have looked at the impact of organic farming on yields and crop productivity for different crops. Our synthesis of reviewed studies suggests that the conversion of chemical-intensive farmland to organic reduces crop yields in the first 2-3 years. However, once various organic inputs have had time to restore the soil's biological activities, organic farming shows comparable yields with conventional agriculture.!? Biomass availability, integration of livestock, effective composting, cover crops, and legumes in the rotation can positively impact yields. A long-term study initiated in 2004 by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) across 12 states and covering several crops shows yield increases over conventional farming of between 5 and 20 percent for crops like ladies’ fingers, turmeric, cotton, black pepper, onion, chili, ginger, green gram, sunflower, maize, soybean, cowpea, etc. However, there was a reduction of 5-20 percent for others like potato, cabbage, French beans, lentils, radish, mustard, cauliflower, baby corn, rice, chickpea, and groundnut.13

Yield differences in organic farming are highly contextual and depend on various site characteristics and agroecological conditions. A meta-analysis of over 300 comparisons (at a global level) reported a 5 percent lower organic yield than conventional under rainfed legumes on weak acidic to weak alkaline soils; - 17 percent (under rainfed conditions), - 3 percent (for specific plants such as fruit) and — 11 percent (for specific oilseed crops). However, under certain other environmental conditions and with acceptable management practices, organic yields can match the conventional results.14 For instance, a 30-year comparison of organic and conventional corn and soybean production by the Rodale Institute showed equivalent yields between the organic and conventional systems, with organic outperforming conventional methods in drought years.15 The package of practices developed scientifically needs to be applied in all agro-climatic regions. Organic farming could be first scaled up in the low resource endowment regions such as rainfed and hilly tracts. As the use of external inputs is low in such areas, comprehensive organic interventions could realize relatively higher yields than without organic approaches on the farms involved.

1. Reduced and rotational manuring practices for reducing the cost of cultivation.

2. Low external input-based organic systems with farming systems approach.

3. How to boost yields among different organic crops in India, and what are the key determining factors?

4. Documentation of traditional knowledge of organic farming.

5. Promotion of identified varieties for organic farming under the development schemes.

6. Nationwide inventory of levels of chemical use.

Like yields, net income and profitability depend on several factors, such as the amount of land available, premium prices, labour charges, market access, farmers’ skills, certification, etc. This complexity makes it challenging to build a general narrative on the income and profitability of organic farming.

With premium prices, farmers could get higher profits than conventional farmers. However, with low market access and linkages, farmers do not benefit from the premium price realization. Instead, they are forced to sell their products in the regular mandis and markets at average prices. Lack of assured market support for organic products is the most significant bottleneck for organic farmers.

The second challenge is the cumbersome and expensive certification process, especially for small farmers. Sikkim — which was formally declared an entirely organic state in 2016 — still suffers from poor capacity building and the lack of a market support system.16 Support to farmers to ensure the effective use and management of an organic package of practices is critical in the first 3-5 years of transition.

The quantity and prices of organic inputs can be both a boon and a challenge. In areas where on-farm organic inputs are not readily available or cannot be made on-farm, farmers have to buy organic inputs and bio-pesticides, which can be expensive and of poor quality and increase the total cost of production.” Similarly, organic farming can be labor-intensive, mainly due to the preparation and application of organic manure and manual weeding. In areas where labour is not available or expensive, this can affect farmers’ overall profitability. However, this does mean greater potential for employment generation under organic farming— a topic that requires further research.

1. Cost-effective technologies for managing organic manure production

2. Agri-implements specific for organic farming operations.

3. Managing labour-intensiveness

SOCIAL IMPACT

There is a need to develop methodologies that can link organic production with health outcomes. We found no such studies in the literature.

Women's involvement and empowerment through organic farming is an under-researched subject in the scientific community of India. However, hundreds of case studies document the benefits and challenges of organic farming for women farmers and their role in scaling up organic practices in India. A wide range of insights on this indicator was collected through many civil society organizations working specifically with women farmers in organic farming.

First and foremost, organic farming has helped improve the agency of rural women in India. The report, Women Leaders — Case Studies from India, by the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Topics contains several success stories.'® Higher incomes from the sale of products at premium prices and reduced production costs have given women economic and financial stability. There are several cases where women have taken up leadership initiatives in and around their farms to promote and scale-up organic farming.

Significant drawbacks were also reported—mainly lack of knowledge. Organic standards follow clear rules and regulations for maintaining quality. Lack of proper know-how of organic practices affects the certification process and prices. Lack of support and risk coverage, especially in the first few years, is a significant hindrance to adopting organic farming. A second problem is an additional workload for women in terms of weeding. Third, they face a lack of investment to transition to organic farming. Costs include transportation to carry organic produce to distant markets, digging water reserves (primarily in the rainfed areas) and certification costs. Finally, there are few markets where women can benefit from the premium price of organic products.

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT

The research on organic farming’s impact on soil health and nutrients is extensive and well-established. One of the fundamental principles of organic farming is managing soil organic carbon and nitrogen to increase soil health. Several studies have shown that adding organic manures, the use of legumes, crop rotation, recycling of residues, the application of biofertilizers, and using compost under organic management systems improved the soil’s physical, chemical, and biological properties, as well as the availability of macro and micro-nutrients.19 20 21

There is a particular emphasis on practicing organic farming in semi-arid and arid dryland soils as they typically have inadequate water retention capacity and low organic matter. In a few areas, the depth of soil is an added challenge. Organic farming improves the physical condition of such soil and its ability to supply plant nutrients. Drylands are also rich in local resources such as minerals (rock phosphate, gypsum, lime), biopesticides (like neem, karanji), and animal waste, which support organic farming methods.22

It is well established that organic farming reduces the potential for water runoff and water erosion using various conservation practices — rotation crops, cover crops, intercrops, and compost. These directly or indirectly improve soil and soil cover quality, encourage water infiltration, and decrease nutrient runoff and erosion.23 However, there is a lack of systemic studies into the impact of organic farming on India's water use efficiency, and this area deserves more attention.

Organic farming can reduce emissions by eliminating synthetic fertilisers, and at the same time, reduce the atmospheric concentration of CO2 through soil carbon sequestration. Many studies have confirmed this globally, but this is still an under-researched subject in India, and more longitudinal studies are required.

No long-term systematic literature was found.

State of available research discussing the impact of conservation farming on various outcomes.

|

Evidence type |

Yield |

Income |

Health |

Gender |

Soil & nutrients |

Water |

Energy |

GHG emissions |

Bio-diversity |

|

Journals |

38 |

14 |

0 |

2 |

12 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

|

Reports |

2 |

2 |

0 |

6 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Articles/Case-Studies |

4 |

9 |

1 |

50 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

Others** |

4 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Total |

48 |

27 |

1 |

60 |

15 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

** Thesis, guidelines, conference papers, etc Source: Authors' compilation

Note — The evidence is from the first 75 results examined in Google Scholar Advanced search and the first 30 results from Google Advanced Search. Only those papers which clearly established the evidence for different indicators were selected.

The following institutions are involved in the research and promotion of conservation farming; a few were consulted for this research:

|

Government institutions |

Research/implementation institutions |

NGOs/Civil society organisations |

|

National Centre of Organic Farming |

Centre for Indian Knowledge Systems (CIKS) |

Organic Farming Association of India |

|

Regional Centres of Organic Farming Systems |

ICAR - Indian Institute of Farming Systems Research partnering with 11 State Agriculture Universities |

Sanjeevani |

|

8ICAR institutes and 1 Special Heritage University under All India Network Programme on Organic Farming |

Organic Farmer Producer Association of India (OFPAI) |

|

|

IIASD: Agriculture Institute India |

DDS Krishi Vigyan Kendra |

|

|

National Organic Farming Research Institute, Sikkim. |

Alliance for Sustainable and Holistic |

|

|

Kheti Virasat Mission |

||

|

Centre for Sustainable Agriculture. |

Source: Authors' compilation

Note — The stakeholders list is indicative and not exhaustive

1 Ramanjaneyulu et al. 2020. Promotion of Organic Farming: Roles of key players. Biotica Research Today 2(8): 731-734.

2 United States Department of Agriculture. 2020. “Organic Production/Organic Food: Information Access Tools”. Webpage. USDA National Agriculture Library. heeps://www.nal.usda.gov/afsic/organic-productionorganic-food-information-access...

3 Kumar, S.R., Spandana, P., Ramanjaneyulu, A.V. and Srinivas, A. 2019. “Components of organic farming”. In: Organic Farming (Eds. Gopinath, KA and Ramanjaneyulu, A.V.). Daya Publishing House. A division of Astral International Pvt. Lid., New Delhi.

4 Yadav AK. n.d. Organic Agriculture — Concept, Scenario, Principals, and Practices. NCOF, Department of Agriculture and Cooperation, Ministry of Agriculture, Gol.

5 Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare. 2020. Lok Sabha Unstarred question no. 2063, ‘Organic Farming’ dated 3 March 2020, Government of India, hrep://164.100.24.220/loksabhaquestions/annex/173/AU2063 pdf.

6 Ramanjaneyulu et al. 2020. Promotion of Organic Farming: Roles of key players. Biotica Research Today 2(8): 731-734.

7 Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare. 2020. Lok Sabha Unstarred question no. 2063, 'Organic Farming’ dated 3 March 2020, Government of India, htep://164.100.24.220/loksabhaquestions/annex/173/AU2063. pdf.

8 Khurana, A. and V Kumar. 2020. State of Organic and Natural Farming: Challenges and Possibilities, Centre for Science and Environment, New Delhi.

9 Ministry of Agriculture 8 Farmers Welfare. 2020. Lok Sabha Unstarred question no. 2063, "Organic Farming’ dated 3 March 2020, Government of India, http://164.100.24.220/loksabhaquestions/annex/173/AU2063.pdf

10 Khurana, A. and V Kumar. 2020. State of Organic and Natural Farming: Challenges and Possibilities, Centre for Science and Environment, New Delhi.

11 Yadav A.K. n.d. Organic Agriculture — Concept, Scenario, Principals, and Practices. NCOF, Department of Agriculture and Cooperation, Ministry of Agriculture, Gol.

12 Sihi D, Sharma D, and Pathak H et. Al. 2012. “Effect of organic farming on productivity and quality of basmati rice.” Oryza 49(1):24-29.

13 Khurana, A. and V Kumar. 2020. State of Organic and Natural Farming: Challenges and Possibilities, Centre for Science and Environment, New Delhi.

14 Seufert, V., Ramankutty, N. and Foley, J. 2012. “Comparing the yields of organic and conventional agriculture”. Nature 485, 229-232 (2012). hutps://doi.org/10.1038/nature11069.

15 Rodale Institute. 2011. The Farming Systems Trial. Rodale Institute, Kutztown, PA.

16 Khurana, A. and V Kumar. 2020. State of Organic and Natural Farming: Challenges and Possibilities, Centre for Science and Environment, New Delhi.

17 Aulakh C.S and Ravishankar N. 2017. “Organic farming in Indian context: A perspective”. Agricultural Research Journal, 54(2): 149-164. DOI 10.5958/2395-146X.2017.00031.X

18 International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics. 2014. Women Leaders — Case Studies from India. ICRISAT, Hyderabad. Available at www.icrisat.org/pdf/Indian-Women-Farmer.pdf.

19 Avasthe, R., Babu, S., Singh, R., and Das, S. 2018. “Impact of Organic Food Production on Soil Quality”. In Conservation Agriculture for Advancing Food Security in Changing Climate (Vol. 1, Issue August, pp. 409-418). Today & Tomorrow’s Printers and Publishers, New Delhi - 110 002, India.

20 Gopinath, K.A., Supradip Saha, and Mina, B.L. 2011. “Effects of organic amendments on productivity and profitability of bell pepper-French bean-garden pea system and on soil properties during transition to organic production”. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 42(21), 2572-2585.

21 Dubey, Y.P. and Date, N. 2014. “Influence of organic, inorganic and integrated use of nutrients on productivity and quality of pea (Pisum sativum) vis-a-vis soil properties”. Indian Journal of Agricultural Sciences 84(10), 1195-1200.

22 Sharma, A.K.,, Patel, N., Painuli, D.K., and Mishra, D. 2015. Organic Farming in Low Rainfall Areas. Central Arid Zone Research Institute, Jodhpur, 48 p.

23 Sivaranjani S. 2019. “Organic farming in protecting water quality”. In: Sarath Chandran C., Thomas S., Unni M. (eds) Organic Farming. Springer, Cham. hteps://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04657-6_1

Suggested citation: Gupta, Nid, Shanal Pradhan, Abhishek Jain, and Nayha Patel. 2021. Sustainable Agriculture in India 2021: What We Know and How to Scale Up. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

The Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) is one of Asia’s leading not-for-profit policy research institutions. The Council uses data, integrated analysis, and strategic outreach to explain — and change — the use, reuse, and misuse of resources. It prides itself on the independence of its high-quality research, develops partnerships with public and private institutions, and engages with wider public. In 2021, CEEW once again featured extensively across ten categories in the 2020 Global Go To Think Tank Index Report. The Council has also been consistently ranked among the world’s top climate change think tanks. Follow us on Twitter @ CEEWIndia for the latest updates.

FOLU Coalition: Established in 2017, the Food and Land Use Coalition (FOLU) is a community of organisations and individuals committed to the urgent need to transform the way food is produced and consumed and use the land for people, nature, and climate. It supports science-based solutions and helps build a shared understanding of the challenges and opportunities to unlock collective, ambitious action. The Coalition builds on the work of the Food, Agriculture, Biodiversity, Land Use and Energy (FABLE) Consortium teams which operate in more than 20 countries. In India, the work of FOLU is being spearheaded by a core group of five organisations: Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad (IIMA), The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI), Revitalising Rainfed Agriculture Network (RRAN) and WRI India.

Contact [email protected]/ [email protected] for queries