Suggested Citation: Das, Pallavi, Jhalak Aggarwal and Vaibhav Chaturvedi. 2023. Unpacking the First Global Stocktake: What’s in it for India and the Global South? New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water

The issue brief unpacks the Global Stocktake (GST) process and analyses the emerging themes in country submissions. It recommends key deliverables of the GST for making it relevant for India and the Global South.

The GST lies at the heart of the Paris Agreement. It aims to support countries in periodically reviewing their collective progress towards the Agreement’s long-term goals of limiting the global temperature rise to well below 2°C. Established under Article 14 of the Paris Agreement, it is expected to help countries course-correct, set more ambitious goals for their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC), and spur international cooperation. The GST is a two-year-long process, and the culmination of the first GST will be at the 28th Conference of Parties (COP28) in Dubai. Over the last three decades, climate pledges have increased. Yet climate action on the ground remains limited due to delivery gaps in action and support, misuse of accounting provisions, non-alignment of commitments with science, and easy exit or non-participation of countries without any punitive measures. In light of the existing geopolitical challenges, structural impediments, unfulfilled pledges, and the rising incidence of climate disasters, it is crucial that the GST process results in strong, actionable outcomes for Parties.

The brief offers a set of key recommendations that the final GST outcome should deliver, in order for it to be relevant for India and the Global South:

The Global Stocktake (GST) lies at the heart of the Paris Agreement and aims to support countries in periodically reviewing their collective progress towards the Agreement’s long-term goals of limiting the global temperature rise to well below 2°C. It is expected to help countries course-correct, set more ambitious goals for their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC), and spur international cooperation. The GST is a two-year-long process, and the culmination of the first GST will be at the 28th Conference of Parties (COP28) in Dubai. Given existing geopolitical challenges, structural impediments, unfulfilled pledges, and the rising incidence of climate disasters, it is crucial that the GST process results in strong political outcomes for Parties.

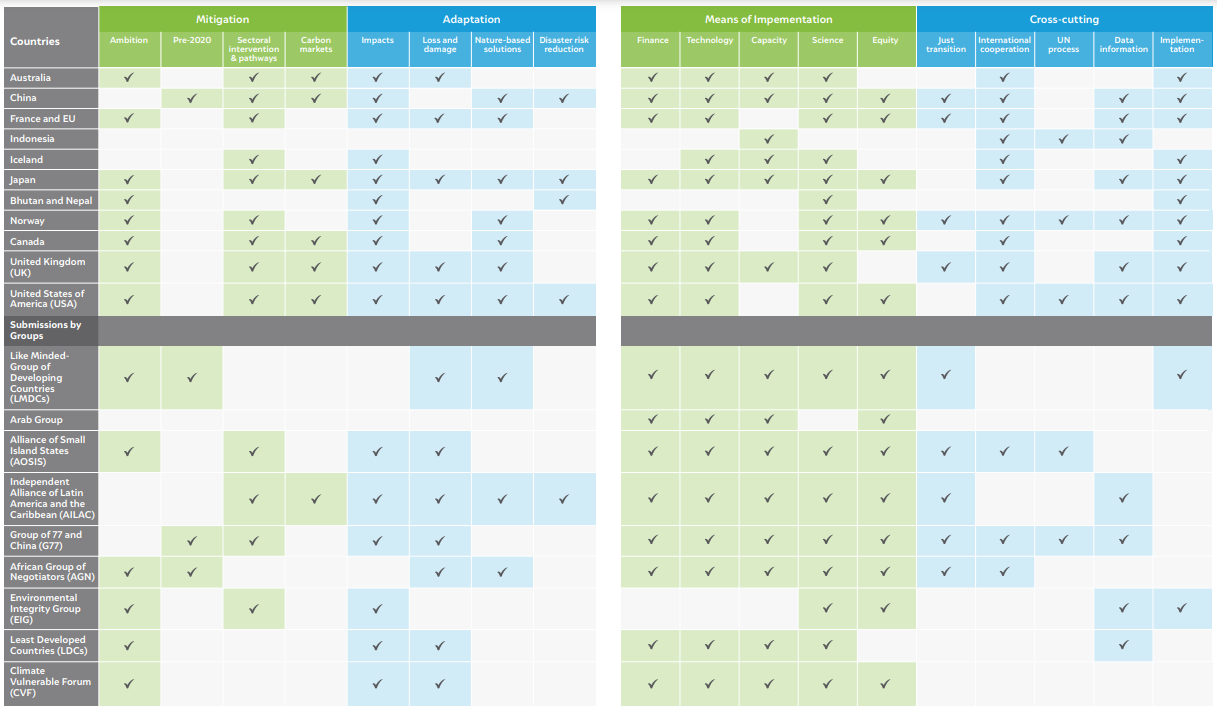

To illustrate and understand the central priorities of the GST, we analysed the Parties’ submissions until 9 March 2023. Our findings are categorised under the following themes:

In this context, The Council offers a set of key recommendations that the final GST outcome should deliver, in order for it to be relevant for India and the Global South:

In the history of climate negotiations, the Paris Agreement has been a one-of-a-kind bottom-up treaty that has brought together both developed and developing country Parties to mitigate climate change and adapt to its unavoidable effects. Established under Article 14 of the Paris Agreement (UNFCCC 2016), the GST process enables the periodic review of the collective progress towards the Agreement's long-term goals of limiting the global temperature rise to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts "to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels" (UNFCCC 2018). In this regard, countries are expected to engage in a 'global stocktaking' process that will inform the next round of NDCs. This process aims to raise the Parties' ambition as well as help countries evaluate the need for enhanced support in light of equity and the best available science by enhancing international cooperation. The GST process follows a participatory, flexible, and inclusive approach to ensure successful and environmentally effective outcomes at COP28 and beyond.

However, there cannot be progress on effective climate action without a serious assessment of past actions. Over the last three decades, developed countries have collectively made an array of climate pledges under the pre-2020 climate agreements: the Kyoto Protocol (2008–12) and the Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol (2013–20). Moreover, progress remains limited so far due to delivery gaps in action and support, misuse of accounting provisions, non-alignment of commitments with science, and easy exit or non-participation of countries without any punitive measures (Prasad, Pandey, and Bhasin 2021). In light of these realities, the GST under the Paris Agreement will need to act as a mechanism to help Parties course-correct, enhance ambition, strengthen accountability, and accelerate the delivery of climate action, while evaluating overall progress. If done effectively, it can offer a scientific foundation and lay the groundwork to guide both Parties and non Party actions. Our issue brief unpacks the GST process, analyses the emerging themes in Party submissions, and recommends key deliverables of the GST for making it relevant for India and the Global South.

The Parties are required to undertake the two-year-long GST process every five years to assess their progress on the long-term goals of the Paris Agreement. The assessment is performed across three themes: mitigation (which includes response measures); adaptation (which includes loss and damage among other aspects); and means of implementation (on mobilisation and provision of finance, technology, and capacity building).

So far, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) processes have guided the negotiations between the Parties that have signed the Convention and the Paris Agreement. However, the GST is an inclusive process that allows non-party stakeholders (NPS) to actively participate in the process through formal submissions and the facilitation of technical dialogues, among others (Srouji, Warszawski, and Roeyer 2022).

Set to be conducted every five years, the GST process comprises and operates in three main phases: (i) information collection; (ii) technical consideration; and (iii) political consideration of the outputs (Figure 1). The GST process started in November 2021, during COP26, and is expected to conclude in December 2023 at COP28. It is facilitated at the UNFCCC by two co-facilitators, one from the developing world and one from the developed world.

In addition to the formal GST process, regional climate weeks have also been used to disseminate information about the GST and ensure that stakeholders understand its process, purpose, and importance in the implementation of the Paris Agreement.

Figure 1 Steps to the Global Stocktake

Source: Authors' compilation

For each of these three phases of the GST, the SB1 and the SBSTA2 have released guiding questions to direct the written submissions and steer the overall conversation. Some of them are discussed below:

The guiding questions for the information collection phase included questions around mitigation, adaptation, means of implementation(finance, technology and capacity-building), and cross-cutting equity themes (UNFCCC 2021). Some sample questions are listed below:

The Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC 2022), the annual NDC Synthesis Report (UNFCCC 2022a), and the United Nations Environment Programme's (UNEP) Emissions Gap Report (UNEP 2022a) and Adaptation Gap Report (UNEP 2022b) have been critical resources for this entire phase. Additionally, the Parties and non-party stakeholders (including UN NGOs and international NGOs) submitted their written inputs.

As per the UNFCCC (2022b), the guiding questions for the technical assessments focused on:

While the first technical dialogue, TD1.1, focused on what has been done so far and where we are, the second technical dialogue, TD1.2, focused on 'how' these gaps can be filled, moving more towards implementable and actionable suggestions, recommendations and discussions (UNFCCC 2022c). The focus of the third technical dialogue, TD1.3, will be on 'what next' (UNFCCC 2023).

This phase is expected to begin around June 2023. The questions for this phase have not yet been released by the SB and SBSTA Chairs, though some early consultations are underway.

To illustrate and understand the central priorities and asks from the GST, we analysed all the submissions by the Parties and the common established negotiation groups until 9 March 2023. There were a total of 20 submissions from the negotiating blocs and Parties and many more from non-party stakeholders. However, this analysis focuses on only the Party and negotiating bloc submissions on mitigation, adaptation, means of implementation (finance, technology and capacity-building), and cross-cutting themes – all larger themes of the GST.

Table 1 Topics of Party submissions

Source: CEEW analysis

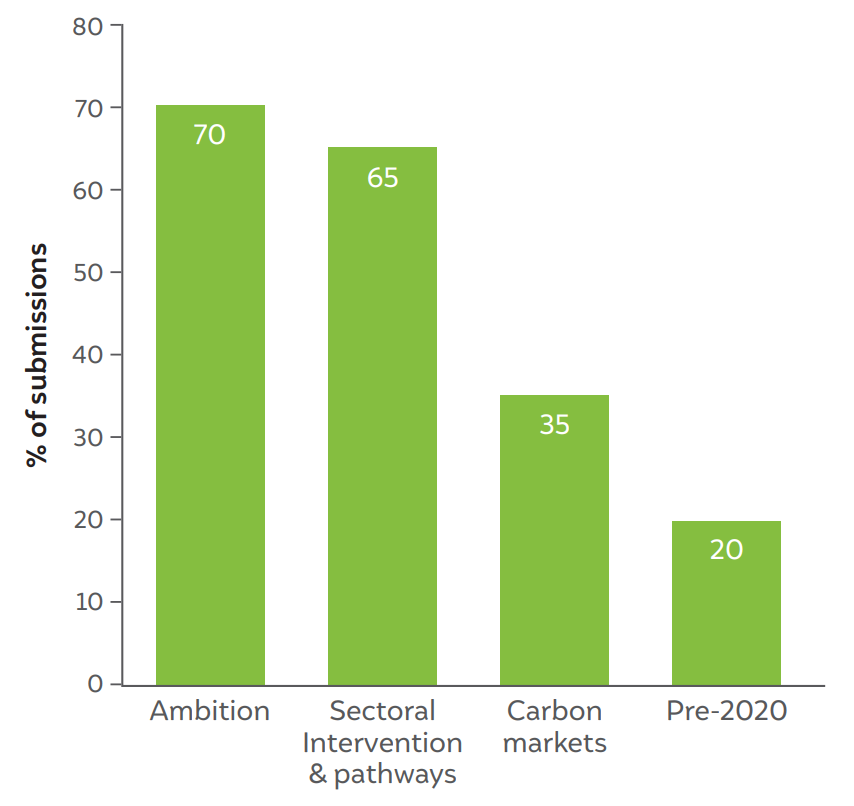

We observed that almost 70 per cent of the submissions highlighted the need for higher and enhanced ambition (Figure 2). Countries' latest climate plans put the world on track for 2.7°C of warming by the end of the century (UNEP 2021). This is nowhere near the Paris Agreement's goal of limiting warming to 1.5°C. Given this disconnect, the ambition gap has been called out and will need to be addressed.

This was closely followed by 65 per cent of submissions, which called for attention to sectoral emission pathways – many mentioned energy sector transitions and renewable energy. Currently, energy sector emissions are the source of around three-quarters of global emissions, making it crucial to switch to cleaner forms of energy for sustainable development. It is important that the GST emphasizes the need for stronger targets and offers recommendations and sector-specific guidelines for rapid transitions across all sectors.

In addition, 35 per cent of the submissions highlighted the role of carbon markets in mitigating emissions. Interestingly, the United States (US) emphasized the role of sub-national carbon markets and highlighted its existing initiatives in creating regional sub-national carbon markets with the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI). This is particularly compelling as national markets have not been very successful in the US.

Figure 2 Emerging themes – mitigation

Source: Authors' analysis

Lastly, 20 per cent of the submissions highlighted the need to account for pre-2020 gaps. Both the Kyoto Protocol (2008–12) and the Doha Amendment (2013–20) have witnessed several setbacks. Despite relatively lower emission reduction targets (5 per cent for Kyoto Protocol and 18 per cent for Doha Amendment), developed countries showed poor participation. Major GHG emitters such as the USA, Canada, Japan, and Russia sat out from these agreements, thereby shrugging off accountability for increased emissions (Prasad, Pandey, and Bhasin 2021). Submissions from developing country Parties and negotiating blocs noted that unfulfilled emission reduction pledges have fuelled mistrust and inaction. Hence, the GST outcome must call attention to the inactions of the past to move forward.

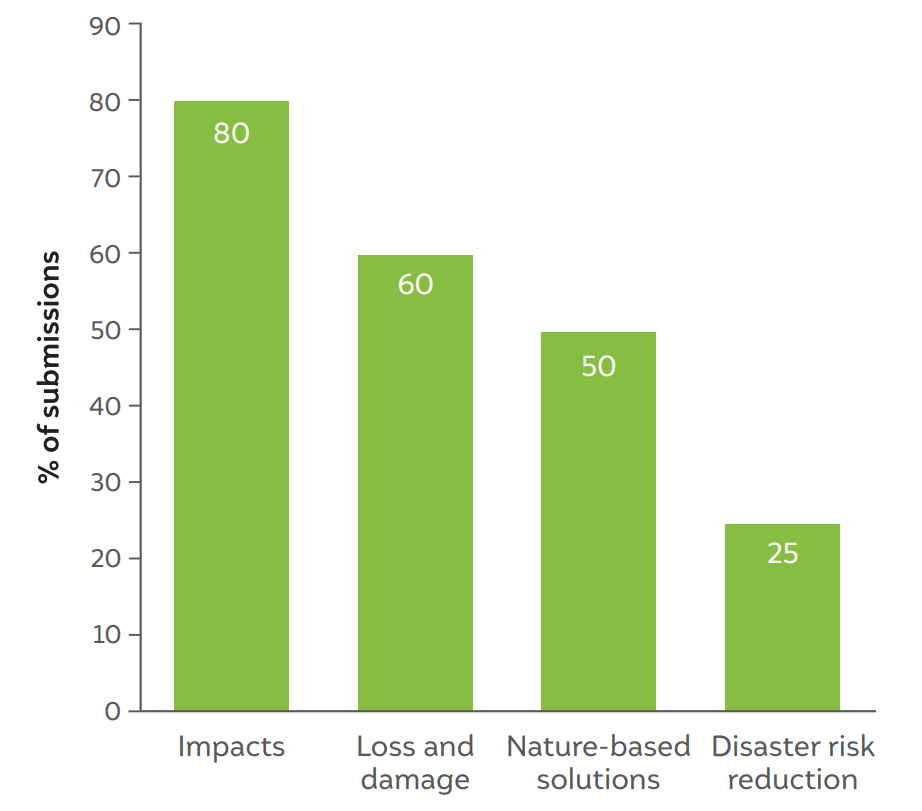

Under adaptation, 80 per cent of the submissions emphasized the rising and heightened impacts that the nations were individually and collectively facing due to climate change and noted the need for more finance from developed countries to combat them (Figure 3). This is particularly critical for developing and vulnerable nations such as India, Bhutan, Nepal, and similar geographies. CEEW’s research shows that 75 per cent of Indian districts are extremely vulnerable hotspots and addressing such impacts is critical (Mohanty and Wadhawan 2021). In light of this reality, the GST needs to provide recommendations to help countries adapt to and address such impacts as well as the need for a quantified Global Goal on Adaptation.

Submissions also mentioned the significance of loss and damage with rising number of disasters (both in frequency and scale). By one estimate, India has suffered losses worth USD 79.5 billion since 1990 due to the escalating impacts of climate change (CRED & UNISDR 2018). While the world witnessed some progress at COP27 with the establishment of the Loss and Damage fund, the submissions clearly articulated the need for immediate, wider, and more actionable recommendations for the operationalisation of the fund in light of equity to avert, address, and minimise the impacts of loss and damage and deliver funds at scale.

And lastly, the indispensable role of deploying nature-based solutions and leveraging the knowledge of indigenous communities and people has been stressed. Today, less than one-tenth of one per cent of global GDP is invested in nature-based solutions (WEF 2021).

Figure 3 Emerging themes – adaptation

Source: Authors' analysis

This meagre number sheds light on the need to mobilise finance and support toward this important solution to address the challenges of our time. Overall, there is a need for accelerated action to determine adaptation needs and recommend a set of actions that are suitable and reflect the national contexts of different nations.

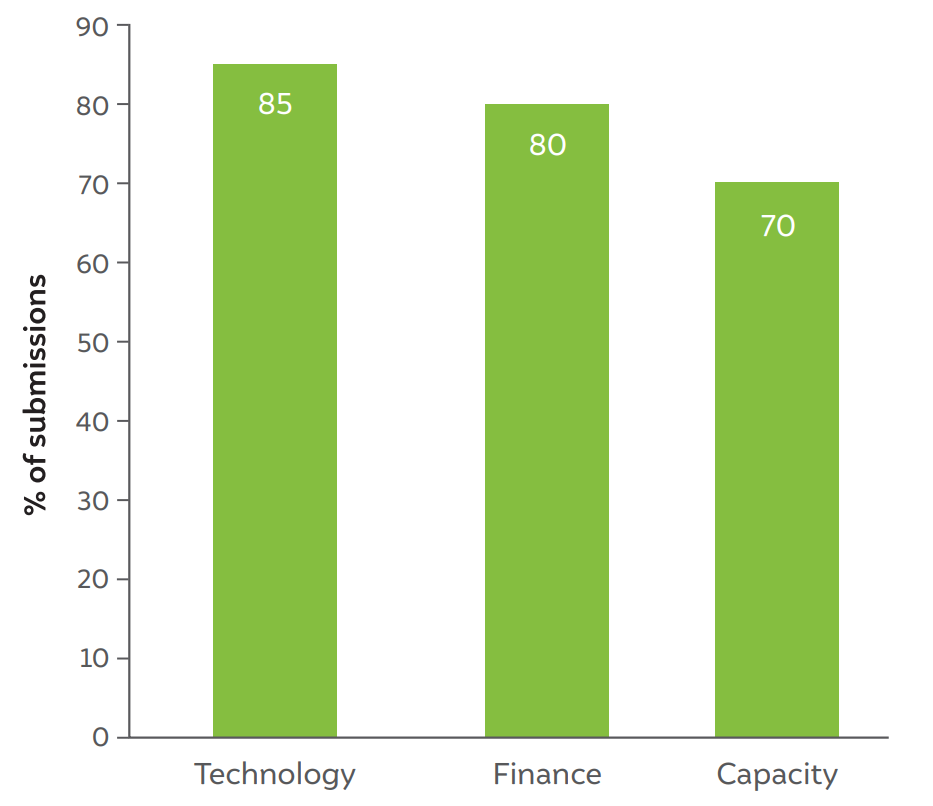

It is well-known that the key roadblocks to climate action are still technology transfer, finance, and capacity-building for implementing mitigation and adaptation measures. About 80 per cent of submissions clearly identified the need for enhanced finance, 70 per cent noted the need for greater capacity-building, and 85 per cent mentioned technologies across mitigation and adaptation activities (Figure 4). We observed that the African Group of Negotiators’ (AGN) submissions emphasised the need to ensure that finance instruments do not lead to further debt crises, given the current domestic economic situation. Research further suggests that around 70 per cent of public climate finance takes the form of debt (Oxfam 2022). Along with this, ongoing global issues such as inflation, the impact of the pandemic, and the Russia–Ukraine war are forcing vulnerable nations to choose between economic prosperity and climate priorities. Hence, the GST outcome should emphasise the need for debt-free and low-cost financing options, especially in the most vulnerable countries. Moreover, the submissions highlighted the crucial role of technology in facilitating the low-carbon transition, particularly in the energy sector, through the use of renewable energy technologies such as solar, wind, hydro, CCUS, and green hydrogen, which are critical for decarbonisation. While some developing nations have pursued a balancing act between economic growth and sustainability in their climate change policies, the GST is expected to underscore the need for greater support for inclusive low-carbon transitions, including greater climate finance, technology transfer, and capacity-building.

Figure 4 Emerging themes – means of implementation

Source: Authors' analysis

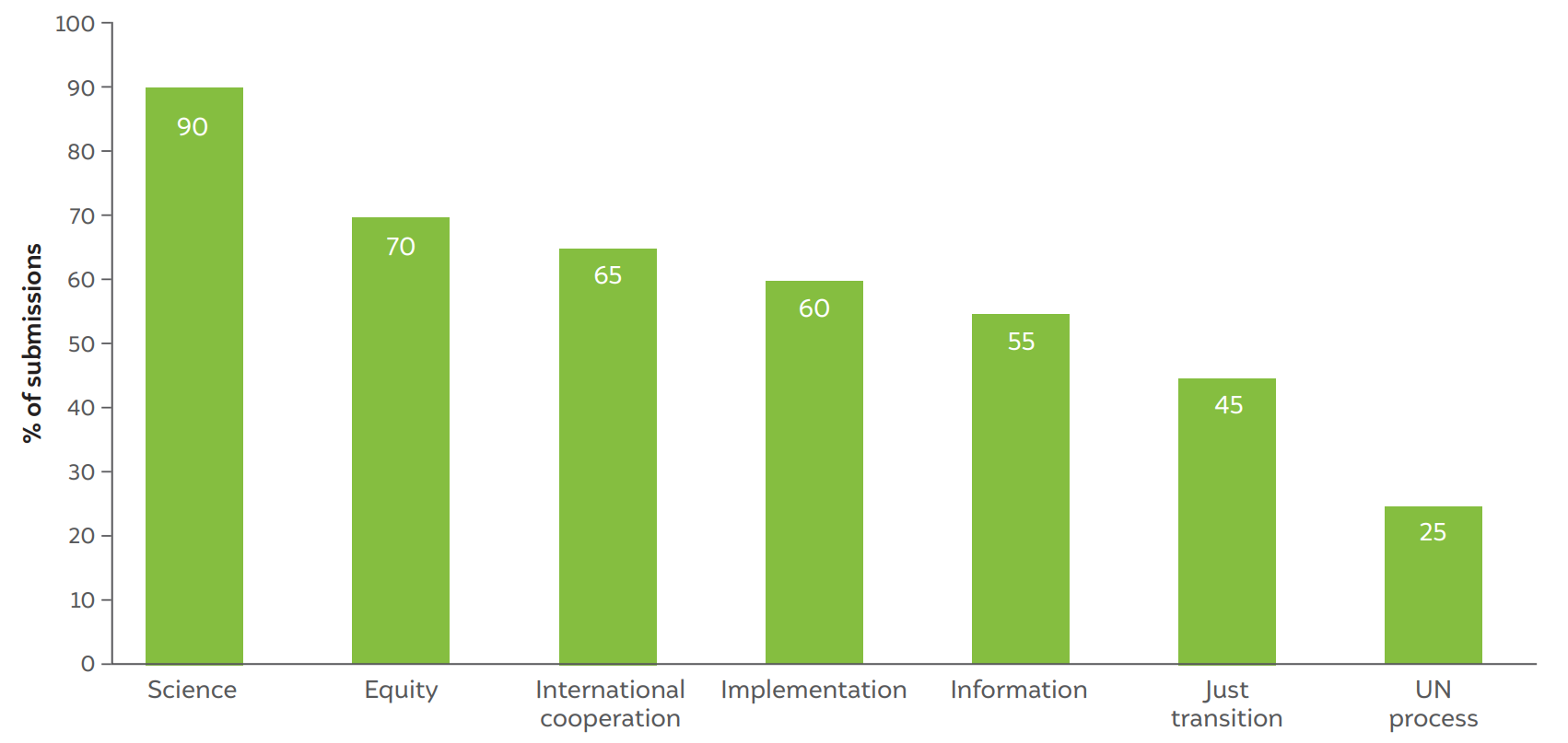

Among the cross-cutting themes, the need for science dominated the submissions, with 90 per cent of submissions mentioning it (Figure 5). Many referred to the global temperature rise discussed in the recently released IPCC AR6 report (IPCC 2022). It is clear that the realities of climate change have been well-established by science – the submissions by the Parties and the negotiating blocs reflect this. Interestingly, the joint submission from Bhutan and Nepal noted the need for a dedicated space to discuss the risks associated with rising temperatures in the cryosphere.

The GST is expected to be conducted in the light of equity, and 70 per cent of the submissions noted the importance of equity in the climate change debate. Interestingly, Norway recommended broadening the concept of equity beyond historical responsibility, to include equal access to opportunities in a zero-emissions pathway, stakeholder engagement in climate policy-making at all levels, and a just transition for the workforce.

Further, the demand for international cooperation was noted by 65 per cent of submissions. International cooperation can only take place if there are enabling frameworks and modalities in place and must support national contexts. Although global finance cooperation has been cited most frequently, there is also a need to identify other avenues of cooperation to enable the transitions we envision.

Additionally, the need for robust and reliable data has been highlighted by many developing country Parties and negotiating blocs in light of their limited capacity. Least-developed countries (LDCs) have particularly stressed the need for better data availability and arrangements to project future scenarios to make more effective, evidence-based decisions and better measure progress. Lastly, other emerging themes from the submissions included the importance of implementation, the need for just transitions, and comments on the UN process.

Overall, science, equity, climate impacts, technology, and finance are the top themes that emerge from Parties’ submissions, and the GST will therefore need to deliver on these. In conclusion, the GST is expected to go beyond just identifying the gaps and elaborate on decisive action for addressing mitigation, adaptation, loss and damage, and diverse financing needs. It should continue to emphasise the importance of equity, and allow systemic global transformations and alignment of the national context and aspirations.

Figure 5 Emerging themes – cross-cutting areas

Source: Authors' analysis

While the GST is a collective exercise to determine how much progress has been made globally and what gaps need to be filled to meet the goals set under Paris Agreement, each country has a unique context, and the political outcomes of the GST will need to cater to those needs to be relevant and spur action on the ground. For India and the Global South, with limited per capita emissions and developmental aspirations, the GST will need to deliver the following:

The GST comes at a critical juncture in the climate debate and is a key lever for securing stronger climate ambition and action as we move forward in this decade. To add real value and set itself apart from existing processes, the GST must offer coherent and targeted recommendations as to what both Parties and non-party stakeholders should do to achieve the Paris goals. The GST will need to consider various country contexts while envisioning the outcome. The GST has the potential to be a catalyst to directing stronger climate efforts, but its success depends on the collective cooperation between all Party and non-party stakeholders. This can trigger coordinated action and replace the existing ad hoc approach and lack of guidance surrounding climate efforts. Given the role of the GST process, it is pivotal to course-correct past actions and renew solidarities between countries, companies, and communities to collaborate and forge partnerships for significant acceleration in the race to decarbonise the global economy.

For India and the Global South to translate messages from the GST and push for actions on the ground, the GST must deliver recommendations on multiple national priorities, including carbon markets, just transitions, accountability, equity, finance, and further best available science in multiple domains.

The final political outcomes of the GST are still uncertain, but India should advocate for targeted and practicable recommendations and look to collaborate with international partners to forge technology and finance partnerships.

Rethinking Ocean Governance in an Era of Climate Urgency

Trust and Transparency in Climate Action

Operationalising the Loss and Damage Fund to Address Climate Impacts

Sustainability-driven Non-tariff Measures