The Energy Conservation (Amendment) Bill, 2022, was introduced in the Lok Sabha earlier this month to amend the Energy Conservation Act (ECA), 2001 and passed into law on 8 August 2022. The latest amendment brings about a renewed focus on sustainability and seeks to support India’s journey towards a net-zero economy by 2070.

The ECA paved the way for the efficient use and conservation of energy by specifying norms and standards for appliances, equipment and construction of buildings. It also established the Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE), a statutory body responsible for the promotion, coordination and enforcement of functions laid under the ECA. The Act was first amended in 2010 to expand its scope and bring the following subjects under its ambit — energy conservation norms for buildings; enhanced energy efficiency norms for appliances and equipment, and a framework for the trade of energy savings among energy-intensive Designated Consumers (DCs). The amendment also increased penalties for offences committed under the Act, including violation of norms for efficiency and consumption standards. Further, it provided room for appeals to be heard by the Appellate Tribunal for Electricity (APTEL).

Now, as the Government of India has brought a second amendment to the ECA to address some of the most pressing issues in the energy sector, we unpack the main features of the new amendments and why they are significant for decarbonising India.

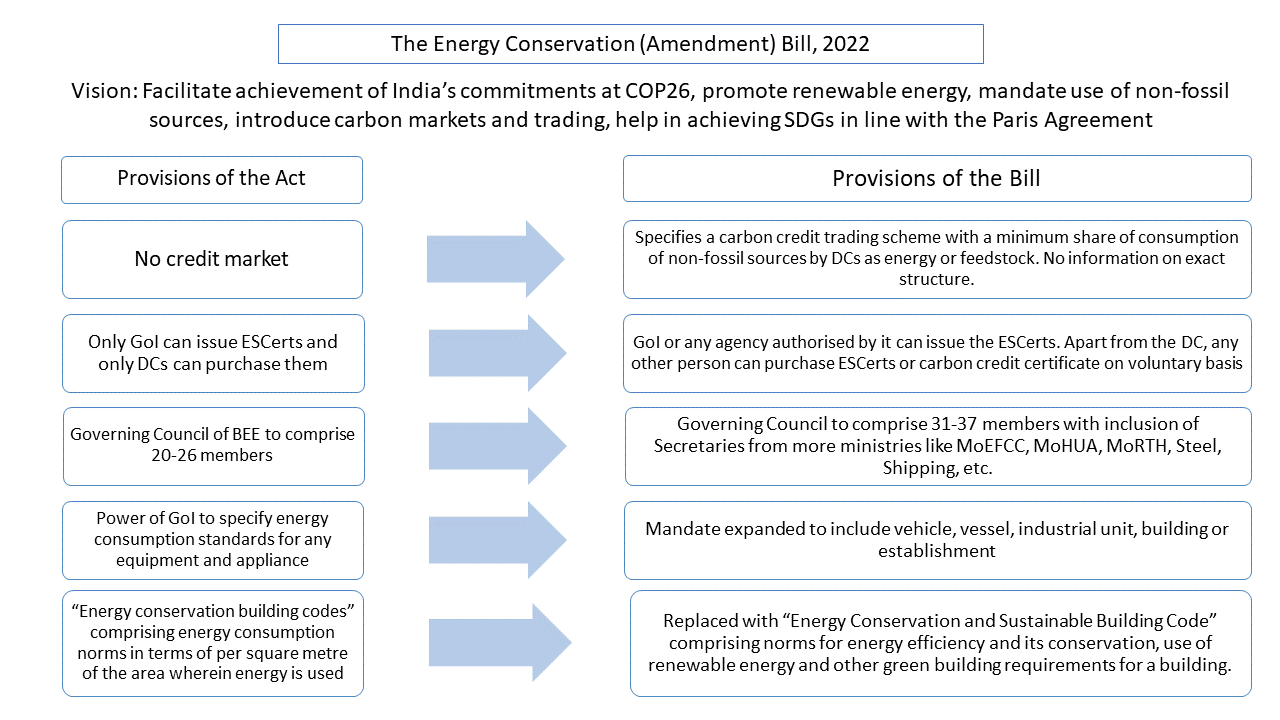

Source: Authors’ compilation based on the Energy Conservation (Amendment) Bill, 2022

1. Establishing a Carbon Market: This is perhaps the biggest development. The amendments empower the Government of India (GoI) to specify a carbon credit trading scheme and a minimum share of consumption of non-fossil sources by DCs as energy1 or directly as an input (“feedstock”). The GoI or any GoI mandated agency would issue carbon credit certificates to a registered entity which would comply with the requirements of the carbon credit trading scheme. This is along similar lines of the Perform, Achieve and Trade (PAT) scheme which was introduced in 2012 and has been one of the most successful programmes of the Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE). PAT was responsible for nearly 63 per cent of all energy efficiency savings in the financial year 2018-192.

The proposed carbon market could be instrumental in three ways — creating a deeper and wider market for energy saving; reducing emissions from various industries; and incentivising a shift to cleaner fuels. While the amendment does not provide details on the carbon market’s regulatory structure or linkages with existing programmes, the Draft Blueprint for National Carbon Markets, published by BEE in October 2021, proposed the development of a Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM) in three phases.

The first phase would be to develop and increase supply by converting energy savings certificates (ESCerts) and renewable energy certificates (RECs) to tradable carbon credits and receiving demand from voluntary buyers, DCs, states (with targets), power distribution companies (through renewable purchase obligations) and airlines. The second phase would entail a supply-side push that would come from project-level registration and their proper validation, verification and issuance of emission reduction units (ERU). And lastly, the third phase would require an eventual move to a cap-and-trade system, like the one operational in the European Union, wherein sectors and companies have a specific amount of emissions allowance.

2. Changes in the mechanism of ESCerts: Under the Act, only the GoI can issue ESCerts as part of the PAT scheme. But as per the recent amendment any agency authorised by the GoI will be able to issue ESCerts. Moreover, currently only DCs can purchase ESCerts but as per the amendment, “any other person” can purchase ESCerts voluntarily. However, the incentive to purchase ESCerts without an obligation or specified targets remains to be clarified, especially given that there is already surplus supply of ESCerts and it is largely a demand driven market.

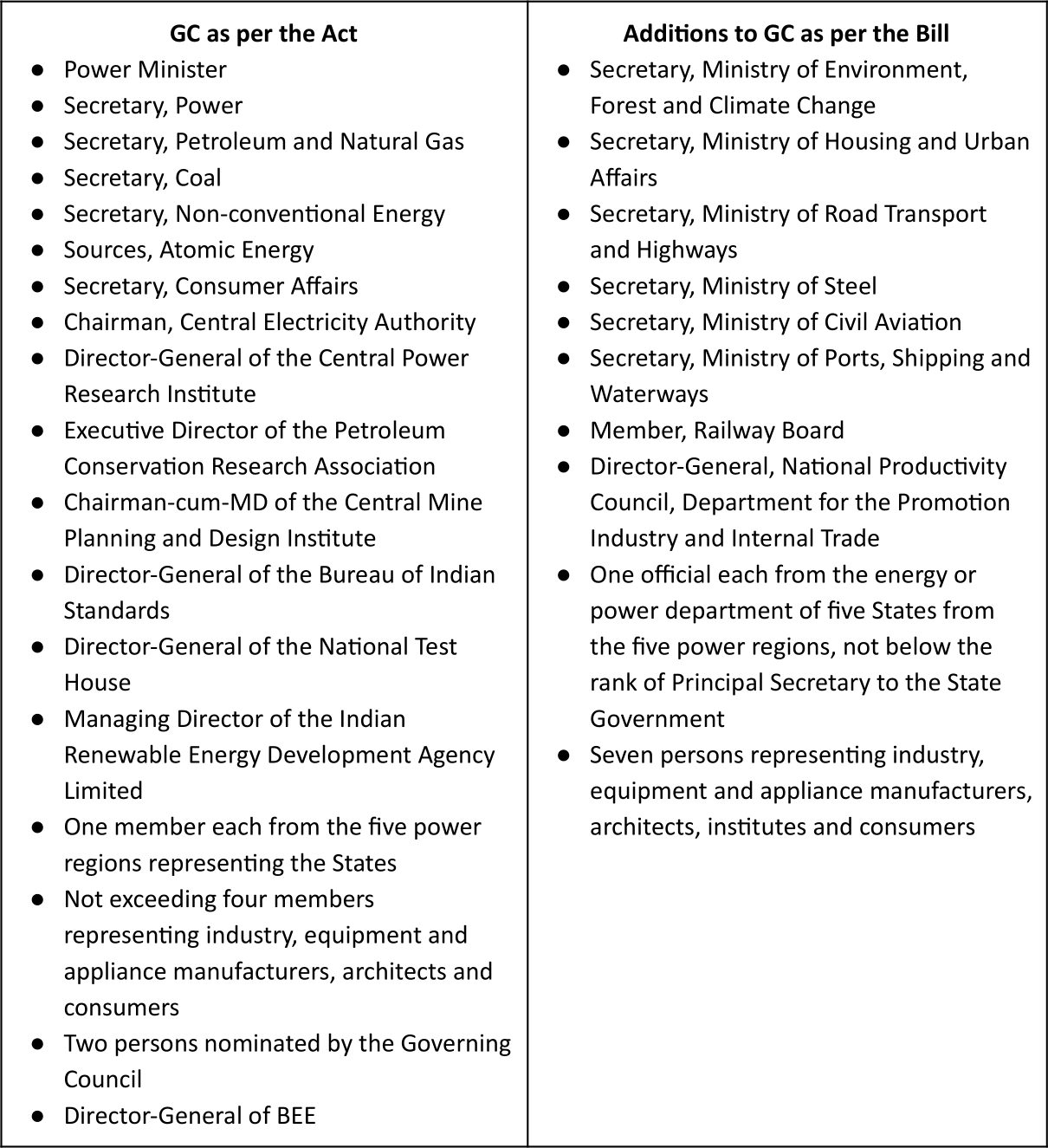

3. Changes to the management structure of the BEE: The size of the Governing Council (the apex body responsible for managing BEE’s affairs) is being expanded from 20-26 to 31-37 members. Below table 1 illustrates the proposed additions.

Table 1: The amendments expand BEE’s Governing Council with a view to smoothening inter-ministerial coordination

Source: Authors’ compilation based on the Energy Conservation (Amendment) Bill, 2022

This is an important step towards recognising the economy-wide approach needed to regulate energy consumption and enhance energy efficiency through inter-ministerial coordination. Implementation of the India Cooling Action Plan (ICAP) across residential, commercial, transport and agricultural sectors is a prime example. However, BEE’s own resources and capacity must increase concomitantly to regulate energy efficiency across economic sectors. Experience of the past two decades has shown that BEE has often struggled to closely monitor and implement its programmes, such as the Standards and Labelling programme for appliances.

4. Expansion of the GoI’s powers to notify energy consumption standards across sectors: As per the recent amendment, GoI can notify energy consumption standards for more entities including vehicles, vessels, industrial units, buildings and establishments. The scope of buildings has also been expanded to include offices and residential buildings, with a minimum connected load of 100 kW or contract demand of 120 kVA. It is important to note that no formal definition of “industry units” or “establishments” has been provided in the amendment. This may have been done to leave room for easier definitional changes through statutory notifications, instead of an extended process of proposing amendments to the Act through the Parliament. Additionally, penalties have been specified for violation of energy consumption standards of these newly added entities, excluding buildings, as they mostly come under the purview of the state governments.

5. Changing “Energy Conservation Building Code” to “Energy Conservation and Sustainable Building Code”: The “energy conservation building codes” referred to norms and standards of energy consumption expressed in terms of per square metre where energy is used. However, the amendments change this to “Energy Conservation and Sustainable Building Code”, which specifies norms and standards for energy efficiency, use of renewable energy and other sustainability-related requirements for different types of buildings. After the amendment, state governments will get a larger mandate to direct owners of large commercial and residential buildings to comply with energy efficiency and conservation standards and deploy renewable energy and sustainable materials for construction.

Residential electricity consumption is projected to increase 10 times by 2047 over 2012. BEE can now notify energy consumption standards for large residential buildings.

The amendment makes strides in facilitating the achievement of India’s renewed Nationally Determined Contributions. However, further clarification is needed on the exact market structure and incentives. The implementation of provisions is contingent upon the manner of engagement with all key stakeholders, including consumers, so as to align them with the vision of the amended Energy Conservation Act.

Notes

1 “energy” as defined under the amendments means any form of energy derived from fossil fuels or non-fossil sources or renewable sources

2 PAT has also achieved a total energy savings of 17.57 million tonnes oil equivalent (Mtoe), avoiding about 31 Mt of CO2 emission in its first cycle and about 61.34 Mt in its second cycle. With six cycles having been notified, PAT has covered 1,073 designated consumers (consuming around 50 per cent of primary energy) from thirteen energy intensive sectors.

3 “motor vehicle” or “vehicle” as defined in the Motor Vehicles Act, 1988, means any mechanically propelled vehicle adapted for use upon roads whether the power of propulsion is transmitted thereto from an external or internal source and includes a chassis to which a body has not been attached and a trailer; but does not include a vehicle running upon fixed rails or a vehicle of a special type adapted for use only in a factory or in any other enclosed premises or a vehicle having less than four wheels fitted with engine capacity of not exceeding twenty-five cubic centimetres

4 “vessel” includes every description of water craft used or capable of being used in inland waters or in coastal waters, including any ship, boat, sailing vessel, tug, barge or other description of vessel including non- displacement craft, amphibious craft, wing-in-ground craft, ferry, roll-on-roll-off vessel, container vessel, tanker vessel, gas carrier or floating unit or dumb vessel used for transportation, storage or accommodation within or through inland waters and coastal waters

Muskaan Malhotra and Dhruvak Aggarwal are Research Analysts at the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), an independent not-for-profit policy research institution. Send your comments to [email protected]

Add new comment