Suggested citation: Agrawal, Shalu, Sunil Mani, Abhishek Jain and Karthik Ganesan. 2021. Are Indian Homes Ready for Electric Cooking?: Insights from the India Residential Energy Survey (IRES) 2020. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

Using data from the nationally representative India Residential Energy Survey (IRES) 2020, this study reflects on the current penetration of electric cooking (eCooking) in India, its usage pattern, its cost effectiveness compared to other clean alternatives, and households’ perception of switching to eCooking from their prevalent cooking fuels. The study also highlights the efforts that could pave the way for the households’ transition to eCooking in the long run

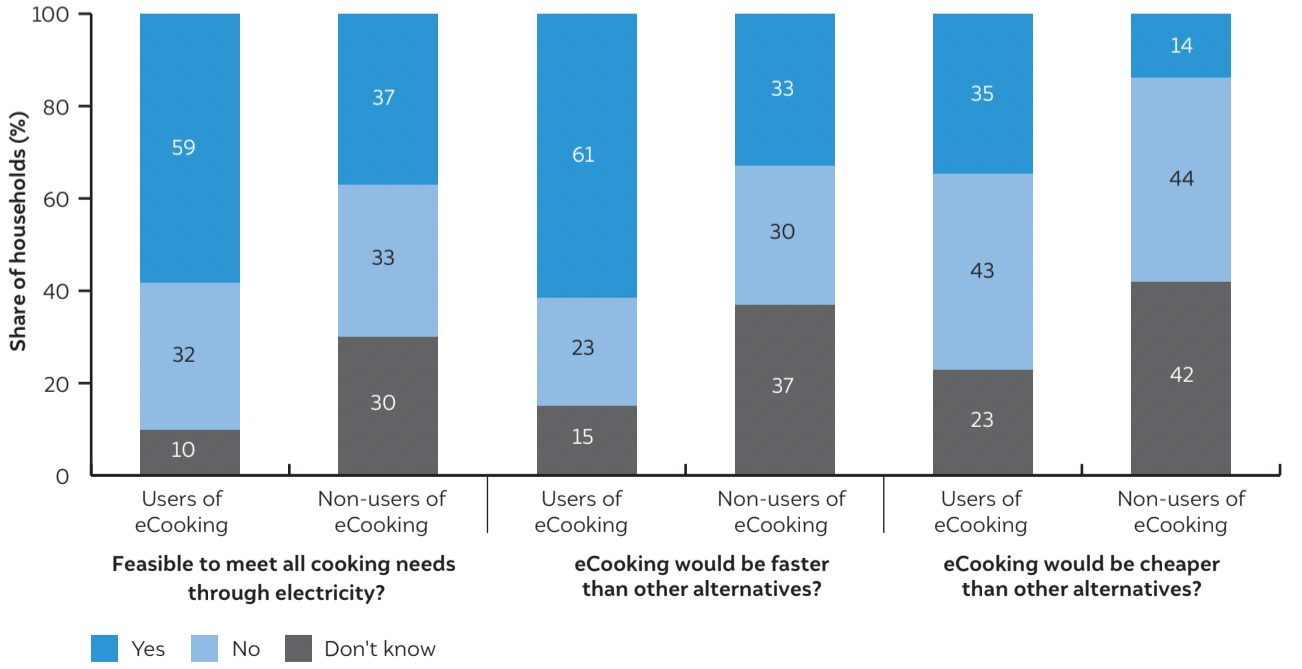

Few Indian households think eCooking would be cheaper than other alternatives

Source: Authors’ analysis

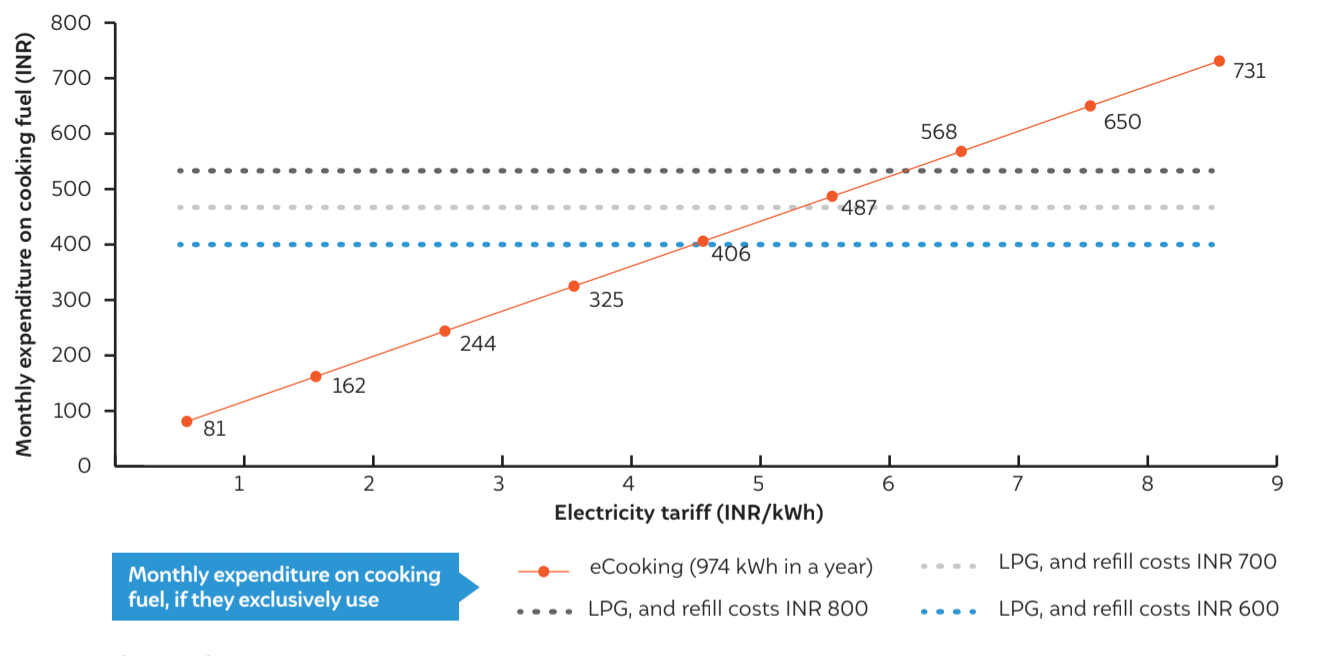

Households getting subsidised electricity would typically find eCooking more cost-effective than LPG

Source: Authors’ analysis

Note: As per an experimental study conducted by Banerjee et al. (2016), we assume that the average electricity consumption for using induction cooktop will be 974 kWh/year. Further, the above comparison is only based on the energy costs of the LPG and electricity, and does not consider capital cost, one-time fixed charges for connection and maintenance costs.

Electricity-based cooking (eCooking) is an emerging phenomenon in India. In February 2021, the Government of India launched the Go Electric campaign to create mass awareness about the benefits of eCooking devices, counter the country’s growing import dependency for liquified petroleum gas (LPG), and support the low-carbon transition (PIB 2021). However, there exists little understanding about the current extent of eCooking adoption and usage in India, its costeffectiveness compared to other clean alternatives, and households’ perception of switching to eCooking from their prevalent cooking fuels. This policy brief aims to fill these critical knowledge gaps with the help of the data and insights gathered from the India Residential Energy Survey (IRES) 2020 that covered 14,850 urban and rural households across 152 districts from the 21 most populous states of India (Agrawal et al. 2020).

As per IRES, five per cent of Indian households use eCooking devices, with a higher prevalence in urban areas (10.3 per cent) than rural areas (2.7 per cent). Induction cookstoves and rice cookers are the most popular devices, each used by nearly 40 per cent of the eCooking users, followed by microwave ovens. Choice of eCooking devices varies across states, with rice cookers dominating in Andhra Pradesh, induction plates in Tamil Nadu and microwave ovens winning the race in Delhi.

At present, most households use eCooking to supplement other clean fuels like LPG. Only half of the eCooking users use it daily, and a majority (93 per cent) rely on LPG or piped natural gas (PNG) as their primary cooking fuel. On a positive note, 60 per cent of the eCooking users perceive that it would be feasible to transition to eCooking entirely. However, we observed high scepticism about eCooking among non-users: only a third perceive eCooking as a feasible option to meet all of their cooking needs, and a sixth feel that it would be affordable to do so.

In terms of recurring expenses, eCooking would be more cost-effective than LPG only for households getting cheap electricity. At an unsubsidised LPG refill cost of INR 800 (USD 11) per cylinder, eCooking would be operationally cost-effective for households paying tariffs less than INR 6.6 (USD 0.09) per kWh.1 However, if the subsidy on LPG resumes with an effective LPG refill cost of INR 600 (USD 8.2) per cylinder, only those who pay a power tariff of less than INR 1 In India, household electricity tariffs vary widely (range: INR 0-11.5 per kWh) across states and consumption slabs, progressively increasing for households with higher consumption. We use a currency conversion factor of INR 73/USD. 5 (USD 0.07) per kWh would find eCooking cheaper. But such households would also be at the risk of moving to a higher tariff slab upon a significant use of eCooking, which may erode the perceived economic gains. High upfront investment needed for eCooking devices and compatible utensils would also deter many households, particularly from low-income groups. This explains why eCooking is currently concentrated among wealthier households in India. However, for households who can avail of it, PNG (depending upon infrastructure availability), would be the cheapest cooking energy fuel.

In conclusion, our analysis indicates presence of significant cost and perception barriers to the uptake of eCooking in India. High-income urban households would most likely be the first to switch to eCooking, predominantly to supplement their cooking energy needs. Supporting this transition along with adoption of PNG would help reduce the demand for LPG in urban areas and free up resources to meet the rising demand in rural areas. Promotion of eCooking at scale would require efforts on multiple fronts, including research and development of energy-efficient, low-cost devices, provision of suitable financing solutions, and reliable electricity services, and in-depth studies to capture the household experience and perception of eCooking under diverse social contexts. Finally, the policy discourse on the role of electricity in India’s clean-cooking journey must also reflect on its implications on future power demand and our ability to service the same through renewable sources. From an emissions perspective, eCooking is currently less preferable than LPG and PNG due to higher emission intensity of gridelectricity. Thus, convergence between the national strategy on greening the grid and the vision on eCooking would be essential to completely decarbonise India’s cooking energy use in the long run.

Drawing insights from the IRES, we find that the adoption of eCooking in Indian kitchens currently stands at a low five per cent. The use of appliances such as induction cookstoves, microwave ovens, rice cookers, etc. is primarily concentrated among urban, wealthy households. Moreover, 93 per cent of the eCooking users rely on LPG as their primary cooking fuel and use electricity as a secondary fuel. Half of the users use eCooking appliances either occasionally or as a backup.

The economics of eCooking vis-à-vis LPG can partly explain these observed trends. Electric cooking appliances have a high upfront cost, which many households, particularly from low-income groups, would find unaffordable. Recurring costs are another critical constraint. At an unsubsidised LPG refill cost of INR 800 (USD 11) per cylinder, eCooking would be operationally cost-effective for households getting subsidised electricity (tariff less than INR 6.6/kWh or USD 0.09). However, if the subsidy on LPG resumes with effective LPG refill cost being INR 600 (USD 8.2) per cylinder, then only those who pay a power tariff of less than INR 5 (USD 0.07) per kWh would find eCooking cheaper. But such households would also be at the risk of moving to a higher tariff slab upon a significant use of electricity for cooking, which may erode the perceived economic gains. Besides economics, perceptions matter too. While 60 per cent of the eCooking users report that it would be feasible to transition to eCooking entirely, households without prior experience of electric appliances (non-users) are mostly sceptical or uncertain about their benefits. In cities where PNG is or would be made available, PNG would be the cheapest and thus consumer’s choice of fuel.

Enabling a Circular Economy in India’s Solar Industry

Community Solar for Advancing Power Sector Reforms and the Net-Zero Goals

Mapping India’s Residential Rooftop Solar PotentialA bottom-up assessment using primary data

Promoting the Use of LPG for Household Cooking in Developing Countries