Suggested citation: Aggarwal, Dhruvak, Muskaan Malhotra, and Shalu Agrawal. 2024. How can India Scale Up Electricity Demand-side Management? Insights from a Multi-state Assessment of DSM Regulations and Discom Action. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

India’s wind and solar energy capacity is expected to increase from just over a quarter of the total installed electricity generation capacity in 2024 and to about half by 2030. Demand-side management (DSM) measures can help cost-effectively integrate such variable renewable energy (VRE) resources while maintaining supply reliability. DSM measures include energy efficiency, shifting load from peak to off-peak hours and influencing the load curve through technologies like distributed generation, energy storage and electric vehicles. However, DSM measures have not been implemented at scale in India so far.

This study provides a comprehensive overview of DSM implementation in India by analysing the DSM Regulations that govern demand-side measures in India, and their effectiveness in eight states (Assam, Bihar, Delhi, Gujarat, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, and Uttar Pradesh). Based on stakeholder consultations and global policy and regulatory innovations, the study recommends five steps to ensure that DSM caters to the power system’s evolving needs.

India’s installed variable renewable energy (VRE) capacity is expected to increase by over three times between 2024 and 2030, from about 118 GW (28 per cent of the installed capacity) to 392 GW (~50 per cent) (CEA 2023c). Maintaining supply reliability while managing VRE’s intermittency is a growing priority for policymakers, system operators, and power distribution companies (discoms). In this respect, policy efforts so far have largely focused on supply-side measures, such as supporting the flexible operation of thermal power plants, enhancing the transmission infrastructure, and supporting grid-scale energy storage.

However, there is growing evidence that using electricity demand as a resource rather than a constraint can be an equally cost-effective strategy. While energy efficiency (EE) can help optimise supply-side investments by mitigating demand growth, shifting loads from nonsolar to solar hours can help increase renewable energy (RE) utilisation and make it more cost-effective (Abhyankar, Deorah, and Phadke 2021). Making loads more supply-responsive can help integrate more RE sooner, leading to lower system costs and cumulative emissions (Anjo et al. 2018). Therefore, designing a clean and cost-effective power system requires a portfolio of interventions that can influence electricity demand in diverse ways. This is collectively known as demand-side management (DSM) (McKenna et al. 2021).

In India, the DSM Regulations (henceforth, “the Regulations”) are one of the primary regulations governing demand-side measures in the power distribution sector. First notified by the state of Maharashtra in 2010, and floated by the Forum of Regulators (FoR) as Model Regulations in the same year, 30 Indian states and union territories (UTs) have notified DSM Regulations by 2024. Despite this, progress on DSM has not kept pace with the needs of the Indian power system (Chunekar, Kelkar, and Dixit 2014; Sasidharan et al. 2021; Josey et al. 2023).

Our study takes a critical look at the DSM Regulations and seeks to answer three questions:

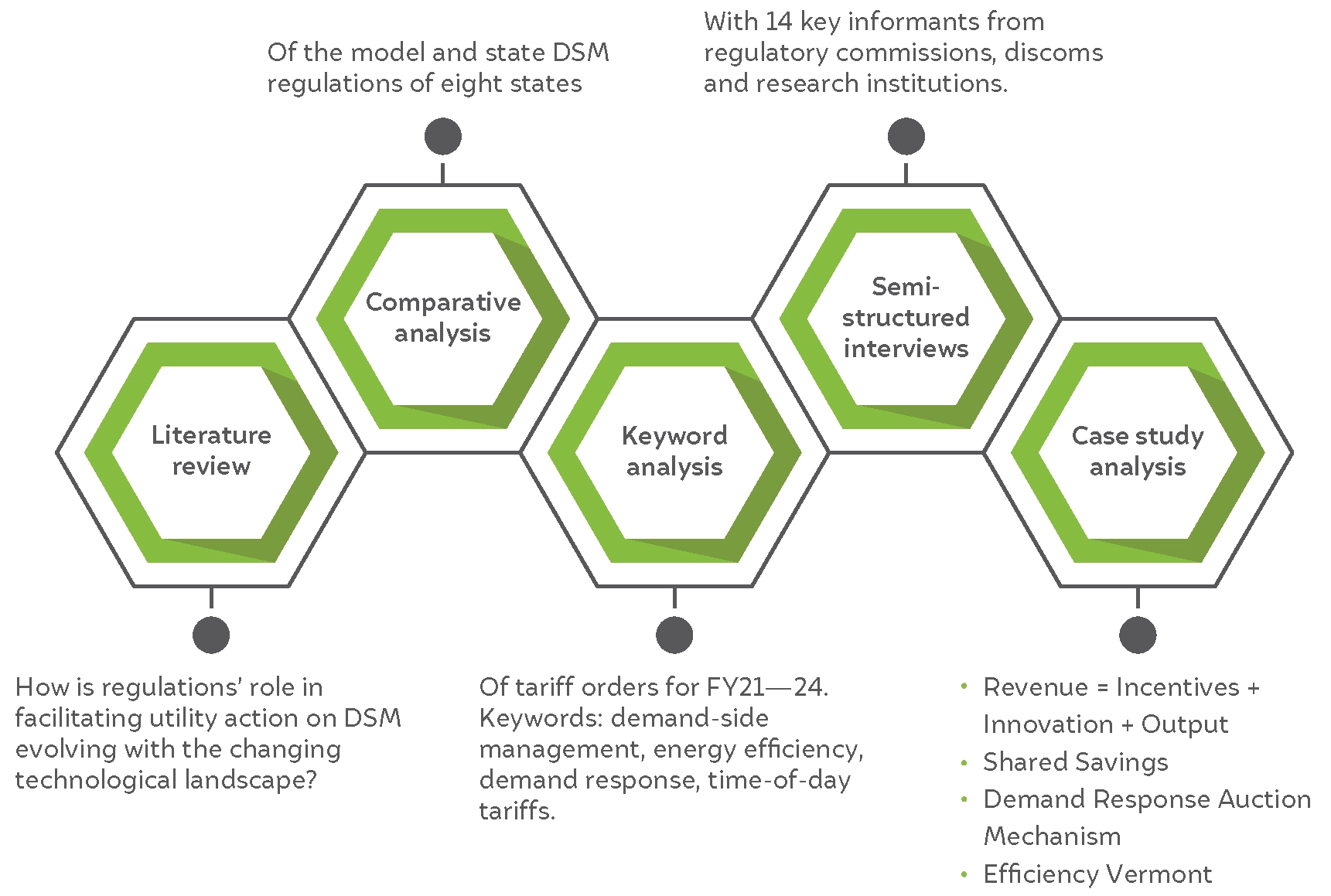

Figure ES1 depicts the methodology we used to answer the research questions.

Figure ES 1 Our five-step methodology to answer the research questions

Source: Authors’ compilation

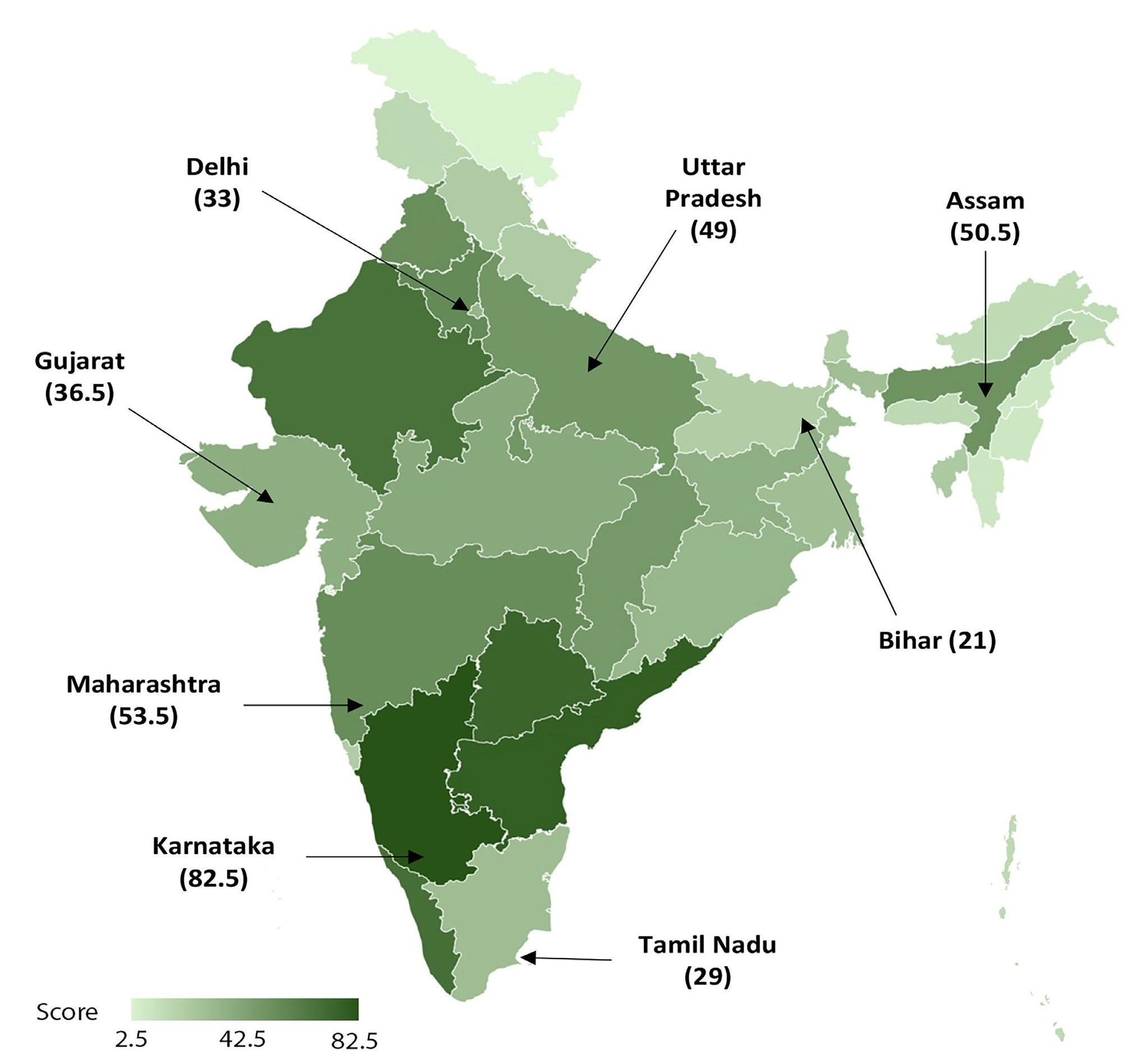

The sampled states span all five grid regions in India, show varied progress on DSM as per the State Energy Efficiency Index (SEEI) 2021–22 (BEE and Alliance for an Energy Efficient Economy 2023), and together constituted half of the all-India electricity requirement in FY22 (CEA 2022a) (Figure ES2).

Figure ES2 The sample contains eight states with varying progress on DSM

Source: Authors’ compilation

Note: SEEI categories (score range ) Aspirant (<30), Contender (30-49.5), Achiever (50-60), Front Runner (>60)

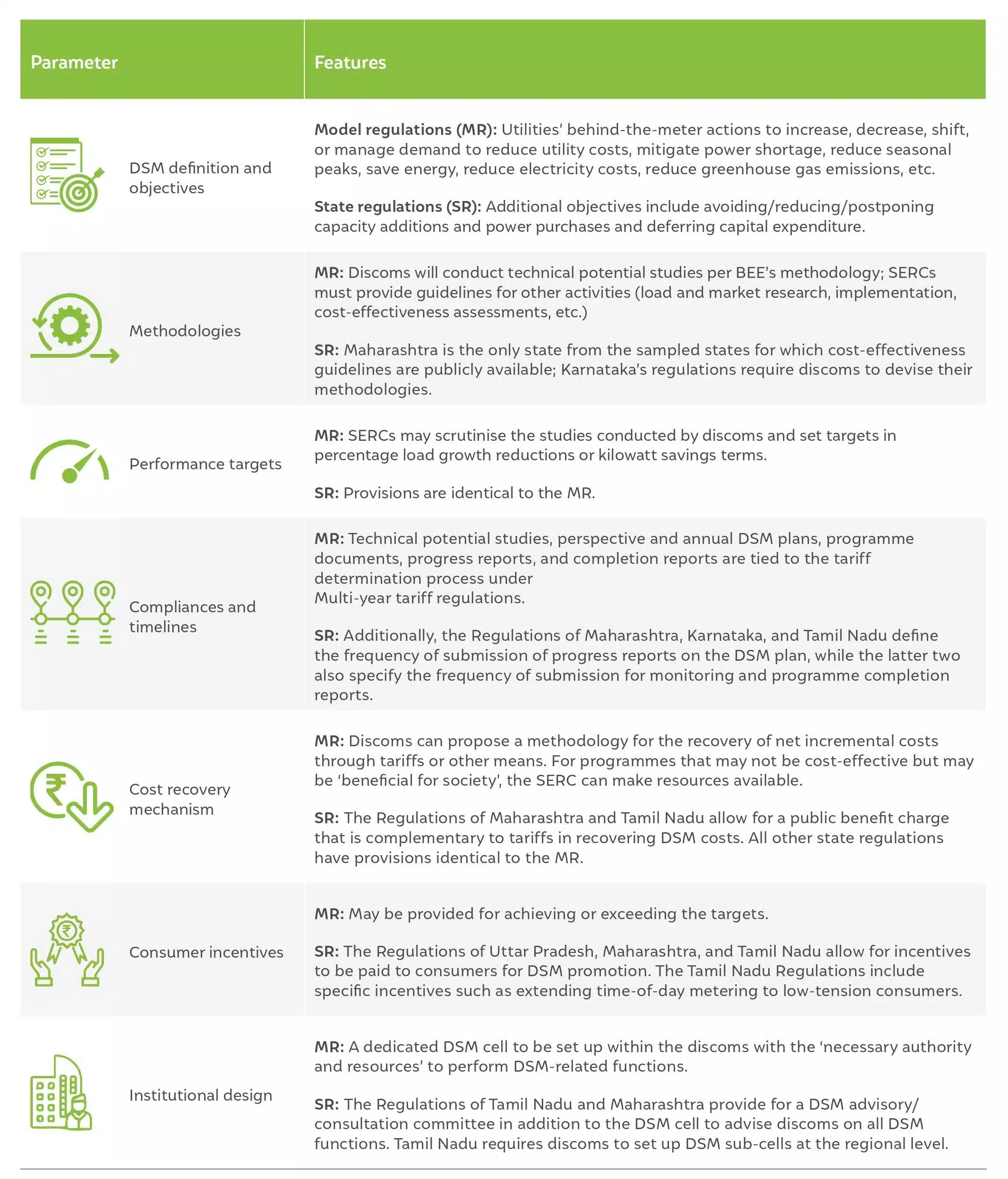

Our review shows that the Model Regulations reflect the context they were drafted in and comprehensively define the roles of DSM, discoms, and state electricity regulatory commissions (SERCs) in assessing its technical potential, setting performance targets, implementing and monitoring programmes, and recovering costs. A comparison across the eight states shows that state regulations largely follow the Model Regulations, with some progressive modifications (Table ES1).

We conducted stakeholder interviews and keyword analysis of tariff orders and found the following:

Our findings suggest that thus far, DSM Regulations have played a limited role in aligning discoms’ operations with the power system’s evolving needs. Private discoms show clearer evidence of taking DSM initiatives than public discoms, perhaps due to their governance structure, a favourable consumer mix, limitations on infrastructure expansion in their service areas, and a proactive approach to innovation.

Table ES1 Many states have added progressive measures in their DSM regulations

Source: Authors’ analysis

A combination of the following factors explains the limited effectiveness of the DSM Regulations:

Given the factors hindering systematic DSM implementation by discoms, we recommend five steps to strengthen the regulatory framework.

India’s power system has evolved from a scarcity-ridden yet predictable grid to one facing swings in supply from surplus to scarce as well as growing demand uncertainty. Given the increase in VRE share in generation capacity, India must tap demand as a resource. Enhancing policy ambition and reforming regulations could empower discoms to experiment with technologies and business models, fail fast, and move quickly to large-scale deployment.

Weather-dependent renewable energy sources that can fluctuate over time are called variable renewable energy (VRE) sources. VRE sources include solar and wind. Along with supply-side measures such as enhancing the transmission infrastructure, and supporting grid-scale energy storage, demand-side management is a cost-effective way to integrate variable RE.

Demand-side management includes a portfolio of interventions that can influence aggregate electricity demand and demand profile in diverse ways. These include lowering the electricity demand across hours, shifting the electricity load, changing the behaviour of electricity consumers, using demand response to help match demand with the supply and reduce peak demand, and leveraging other ‘behind-the-meter’ technologies like distributed generation, storage, and electric vehicles.

The Demand Side Management Regulations are one of the primary regulations governing demand-side measures in the power distribution sector. First notified by the state of Maharashtra in 2010, and floated by the Forum of Regulators (FoR) as Model Regulations in the same year, 30 Indian states and union territories (UTs) have notified DSM Regulations by 2024.

India aims to integrate at least 500 GW of non-fossil power generation capacity by 2030, of which about 400 GW will be VRE. Evidence shows that DSM will be critical for cost-effective VRE integration. For instance, shifting load to solar hours from non-solar hours can help increase the utilisation of VRE sources. Modifying the load profile instead of treating it as a constraint can help integrate more RE sooner and with lower system costs and cumulative emissions.

Improving Discoms’ Financial Viability

Assessing the Value of Offshore Wind for India’s Power System in 2030

Making India’s Advanced Metering Infrastructure Resilient

Enabling a Consumer-centric Smart Metering Transition in India